Number Ones: Lost Frequencies’ ‘Are You With Me?’, And The Uncomfortable Marriage Of Pop Music And Dance

The differences between Lost Frequencies’ ‘Are You With Me?’ and its source material –- a sped-up sample of a country tune –- says a lot about why some listen to pop music, and some listen to dance.

Bringing his popular column for The Vine to Junkee, Tim Byron takes a deeper look at the top song on the ARIA Singles Chart.

–

In recent years, dance music at the top of the charts has been occasionally inclined to get a little bit country. Avicii’s recent #1, ‘Wake Me Up’, combined Mumford-esque banjos’n’heys with big dance beats. Pitbull and Ke$ha’s ‘Timber’ had a prominent countrified harmonica, and Ke$ha singing with that distinctive Southern accent that signifies ‘country’, even when Aussies do it. There were also big dance beats, of course. And if you ever wanted further proof that the world of dance music has clearly forgotten the lessons that should have been learned from the reign of horror that was Rednex’s ‘Cotton Eye Joe’? Well, Lost Frequencies’ ‘Are You With Me?’ is now at the top of the charts.

‘Are You With Me?’ is based around a sample taken from the first half of the first verse of a 2012 song by country singer Easton Corbin. Lost Frequencies (a Belgian producer named Felix De Laet) takes that song fragment and refashions it into dancefloor manna. And it really has been refashioned.

The original sits at a very leisurely 72 beats per minute; it’s a chilled out ballad. But after Lost Frequencies have had their way with it, the song is at a much-faster typical-disco 122 BPM. Where Corbin ambles his way through the sampled section of the song in 38 seconds, Lost Frequencies speed through it in 22 — a dramatic acceleration which obscures the overbearing over-enunciation of Corbin’s Southern accent, but has the less beneficial effect of rendering his lyrics nonsensical. (“Drink some margharitas by a string of blue lights” becomes “drizza-Macarena-bias-tree-uh blue lights“, sung by someone who has had ten black coffees in the last hour.)

There’s deeper differences between the two versions, though, which say a lot about the differences between dance music and pop music. At one level, these differences are blindingly obvious: Dance music is for dancing, and pop music is for being popular. If a dance tune is popular, it’s both dance music and pop music! Sorted.

But while we like to see pop music as a sort of lowest common denominator — if it’s popular, it’s pop! — in truth, pop music is about more than that. It’s a musical genre with a set of conventions, the way that bebop jazz is, or death metal.

The Difference Between Pop And Dance

To put it simply, pop music is about the song. And it’s about a certain kind of song, the kind that uses verses and choruses as a frame for hooks. Pop music is a lean, mean meme machine, a brutally efficient delivery mechanism for the kind of sounds that might bounce around your head all day. The build-up of a verse, the explosion of a chorus, the clever little musical elements, the repetition; it’s all about getting a song to inhabit your head. And it so happens that the songs that inhabit our heads often sell quite well.

In his book The Interpretation Of Dreams, Sigmund Freud argued that your brain often has nefarious subconscious reasons for putting a particular song into your head (because of course he would argue that). But while Freud obviously had some odd ideas, this one has a grain of truth to it. Whether it’s Taylor Swift’s “haters gonna hate hate hate hate” in ‘Shake It Off’, Beyonce’s “to the left, to the left” in ‘Irreplaceable’, or Blur’s “all the people, so many people” in ‘Parklife’, the pop music we listen to at least feels like a running commentary on our lives, narrated by some subconscious self that we only dimly sense.

Dance music, on the other hand — whether EDM or deep house or trance or whatever — is an incitement to move your limbs. Each genre of dance is an incitement to move your limbs in different kind of ways, but dance music must prioritise the beat that you’re moving your limbs to, rather than the meme. And so dance music is all about groove, all about vibe. Of course, it’s plenty possible for dance music to prioritise the beat while still cramming in a song with pop verses and pop choruses. Mark Ronson’s ‘Uptown Funk’, for example, both works as an impossibly perfect pop song and as eminently good dancefloor material. But in a lot of dance music, the song stuff tends to feels like a distraction; you see dance snobs in YouTube comments and forums turning their nose up at dance music that’s trying to be pop music too.

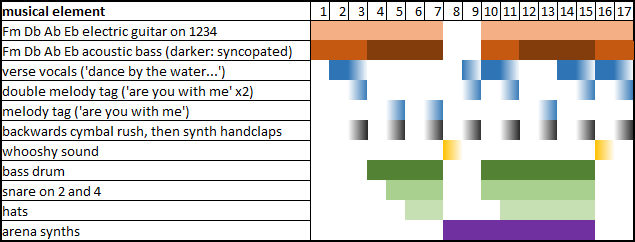

Because the beat is the main thing, dance music producers are not beholden to verses and chorus. And so in dance music, musical elements — synth sounds, voices, samples — often make an entrance, hang around until you forget they’re there, and then exit stage right. And as long as the beat goes on when the other elements drop out, everyone’s happy.

There are thousands of examples of music using this kind of logic, but Daft Punk’s ‘Around The World’ — with its famous Michel Gondry video clip, featuring dancers symbolising the various musical elements — is probably the best. ‘Around The World’ is built around five different musical elements, and Daft Punk spend the song exploring them, and how they work together. There’s no chorus, per se, just a catchy bit that comes in occasionally. Of course, that catchy bit is hella catchy, but the hooks are almost incidental to the exploration of sound and the beat.

This kind of ‘elements coming in and out’ structure is also the basis of Lost Frequencies’ ‘Are You With Me?’. Easton Corbin’s original song, by contrast, has a pop song structure — verse, chorus, verse, chorus, middle 8, chorus, etc. Country music, of course, is more or less just pop music for people who identify with the country; if anything, it actually follows pop song structure more slavishly than mainstream pop. The Corbin song, in fact, was co-written by Shane McAnally, a songwriter best known to non-country audiences as the co-writer of Kacey Musgraves’ witty country pop (‘Follow Your Arrow’).

McAnally, you can rest assured, is a man who knows how to deploy a pre-chorus, to maximise the effect of a chorus.

I wonder whether Lost Frequencies would know or care what a pre-chorus is. In his version of the song, the whole thing revolves around an 8-bar phrase that repeats for the entire song. It’s a peculiar structure for a dance song, in some ways. In each 8-bar phrase, the beat builds momentum, builds entrainment to the groove, for 7 bars; then, there’s a crescendo of backwards cymbal whoosh. The beat stops, as warbly fast-forward-Corbin sings “are you with me?“. And then there’s two drum machine handclaps to signal the start of the next 8-bar phrase. And repeat, for literally the entire song.

Elements — an arena synth, a bass line, a guitar part, various percussion and drum sounds — come in and out, as you can see in the graph below (which I created with the help of musicologist Jadey O’Regan), but they’re a sideshow. The main event is those 7 bars of beat, and then the breakdown: “Are you with me?”

All of this explains why, to my pop music-listener ears, Lost Frequencies’ ‘Are You With Me?’ is pretty boring. It feels like nothing happens. It just repeats over and over again. The elements coming in and out the song don’t have the same clever geometry that you hear in, say, Daft Punk’s ‘Around The World’. And then it’s over in a “is that all there is?” kind of way. I mean, at 2:16 it barely has time to establish a groove, and from a pop point of view, there’s not much in the way of logic to the song. Why did Lost Frequencies decide to pull out the beat 53 seconds into the song — barely 30 seconds after it started up? Why is the full verse repeated only once, before running through the 8-bar phrase twice with only the hook of the song at the end?

It feels like a riddle wrapped in a puzzle inside a hell of a lot of repetition.

What Is This Song Actually About?

Of course, from the perspective of someone on the dancefloor, ‘Are You With Me?’ might make much more sense. I mean clearly it has to, otherwise it wouldn’t have been a hit across Europe, and now a #1 here. So let’s look at that beat. The sound of the song isn’t the all-encompassing thumping club beat thing you’d get with something remixed by David Guetta in 2011. Instead, the sound of ‘Are You With Me?’ is pristine — perhaps even a bit prissy. At 122 beats per minute, it feels quite measured; finely calibrated, rather than booming. It’s not a song for someone who’s already pinging like a bastard. Instead, the song wants me to picture a scene — implied by the titular refrain. The scene involves a group of friends who are still tentative about their dancing. They only just got to the festival/club/whatever. They haven’t yet shrugged off the cares of the world, but they’re ready to. And so, listening to Lost Frequencies, this group of friends hears the beats drop out. The braver of the group of friends — the ones already dancing — sing “are you with me?” at their more timid friends, and repeat as more and more of the timid friends join the dancefloor. A couple of minutes in, everyone’s dancing, so it’s time for something else.

And therein, I think, also lies some of the appeal of the song to people who aren’t on dancefloors: it’s a song of anticipation, a song of tentatively looking forward to something. It’s a song that probably got played in a lot of road trips out to Splendour In The Grass. And perhaps the seemingly random choices in the song help create a feeling of tentativeness that a producer genius like Max Martin would have to go against every songwriting instinct in their bones to obtain.

The smoothness and the repetition of the song also make it work pretty well as background music. It’s music you can imagine soundtracking a commercial for an upmarket European car; the kind of commercial that features a stylish, handsome man impressing a sophisticated lady, who shows her appreciation with a raised eyebrow and a half-smile rather than the kind of ‘bow chicka wow wow’ action you get in a Lynx ad.

It’s music that burbles away reassuringly in the background while you focus on other stuff — that stylish Germany lady with the raised eyebrow, for example — and which is done and dusted before its repetitiveness really starts to become blindingly apparent. And so if I’m finding it boring, chances are that this is purely because I’m actually listening to the song, rather than using it.

–

Tim Byron completed a PhD in music psychology, plays in too many bands, and chronically overanalyses everything musical. He has written for Max TV, Mess+Noise, The Guardian, The Big Issue, and The Vine.