On Nick Cave, And Why Australians Move Overseas

As Nick Cave's extraordinary documentary is released nationwide, an Australian expat reflects on how leaving home has become part of Australia's national story.

To love Nick Cave and his music is to have access to the self-contained and entirely coherent world that he inhabits. It’s a world shaped by his work, his personas, and the mythology of the Prodigal Son who is never, not ever, coming home. You can spot which part of that world a Nick Cave fan vibes to — junkie, outlaw, bookie, lover — by picking us out in the crowd.

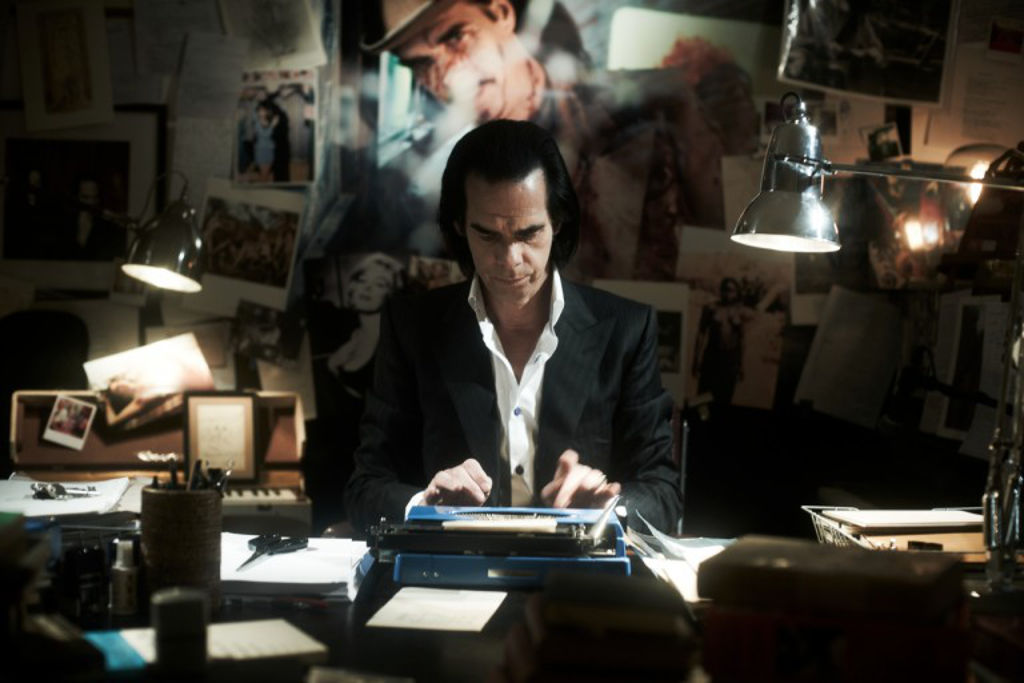

Best known as the frontman for the seminal post-punk group The Birthday Party and, after its 1983 disintegration, Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds, Nick Cave can also lay claim to being a lecturer, actor, film-score composer, screenwriter of the films The Proposition and Lawless, and a novelist, of And The Ass Saw The Angel and The Death of Bunny Munro (the latter of which is probably best forgotten). He is a man described in John Wray’s recent New York Times profile as somebody who “has always appeared to be performing in a movie only he himself could see,” and as of this month he is touring the world in preparation for the release of a film, 20,000 Days on Earth.

The film, co-written with artists Iain Forsyth and Jane Pollard, is notionally about Cave’s life, but it’s located at the foggy crossroads of fact and fiction that confuses any and all notions of straightforward ‘documentary’. As the title suggests, it’s an investigation into the way time passes, as well as memory and artistic longevity. The film tells you less about Nick Cave and far more about the effect of Nick Cave.

Because the thing is, the command of Nick Cave’s music doesn’t rest at the level of the song. It insinuates itself into the ear of the listener. We’re seduced into going somewhere else, towards a place where we too are abandoned and lost. And that state, we are led to understand, is a necessary prelude to an experience of grace. To fall into it, to believe in it, to drink the Kool-Aid, is a kind of exercise in collaborative mythmaking.

Concert To The Left; Church To The Right

A few weeks ago on a Sunday night, a man stood on 34th Street outside the Hammerstein Ballroom where Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds were about to play their second New York show. The man cried out, asking us all to “kneel down at the feet of the Lord”. People milled about on the pavement, mostly ignoring him, and in fact he was barely audible over the general hum and the shouts from security guards directing the crowd with their voices and arms. “Concert to the left; church to the right,” they shouted.

On the far side of the theatre, at a separate entrance the man had stationed himself outside of, stood a tall billboard, with an arrow directing people inside. “Hillsong Church Evening Service”, it read, in the warm and relentlessly cheerful typeface which, however ersatz and buoyant its lettering, I associate with long god-awful stretches of motorway on the suburban fringes of Sydney.

When I was fourteen — the same age, incidentally, when I began listening to Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds — there was a girl in my year who spoke about Hillsong services in the glassy-eyed way that other fourteen-year-old girls might talk about horses or Saturday afternoons spent in the back row of suburban multiplexes with boys whose voices had not yet broken. One lunch period the girl approached me in the school hallway and invited me to her youth group the following Friday night. “I’ve told them all about you,” she said, and they had all come to the conclusion that something needed to be done. They had offered, she said cheerfully, to exorcise me.

I have never been a religious person, but from a very young age I was attracted to music with the kind of fervour that, if I was a different kind of girl in a different time, might have been directed towards Jesus. The sense of being lost inside and physically overwhelmed by something much larger than myself, to give in to self-erasure, appealed to me greatly. It’s not a great leap to think of seeing a concert in the same light as going to church.

When I was fourteen I first heard the voice, saw the eyes. Heard him threaten: “I’m going to tell you about a girl“. The music of Nick Cave invited me inside the part of myself that was graceful, literate, wanton, unrepentantly romantic. Despite how long and intensely I’ve loved Nick Cave, I hadn’t ever seen him in concert until three weeks ago in New York. I was too young to have grown up alongside his music; it was something I discovered on my own as a teenager in the jumble of my father’s old CDs. I’m telling you this is not as an exercise in disclosure or self-revelation, but to explain that when the music of Nick Cave tore through my adolescence it determined forever the shape of some of my dreams.

“The music of Nick Cave invited me inside the part of myself that was graceful, literate, wanton, unrepentantly romantic.”

Dreams, like most stories, have two lives: in individual memories, and in the collective imagination. The stories we tell ourselves have the functionality of light, endlessly refracted. They orient us to the archetypal landscape. They get into the atmosphere. The stories form a kind of cohesive daylight without which we’d lose our bearings. They seem utterly familiar, and so we rarely, if ever, assess their impact on our behaviour or beliefs, because they surround us, like the air; like the light.

Which is to say that there is a cultural narrative particular to Australia – a narrative that Nick Cave and The Bad Seeds are indelibly written into the pages of. It’s a narrative that I wasn’t fully aware I had willingly written myself into as well. I figured it out standing on the pavement between the doors to the concert and the doors to the church.

Why Australians Leave Australia

Right now, there are over a million Australians who don’t live in Australia. 4.6% of us. It’s an unprecedented number, and a number that’s likely to grow what with evolving labour markets and globalisation. Demographically, the Australian diaspora is young, highly skilled and highly educated, likely to be from either Sydney or Melbourne. While there are significant numbers of Australians living in Greece, Singapore, Hong Kong and New Zealand, the most popular countries of departure have remained consistent over the generations – the UK and the US. There are over 20,000 of us living in New York alone. I became one of them last year.

The draw to London and New York as places for Australians to learn and develop is partly historic. There were earlier generations of Australians — generations that referred to England as ‘the home country’ and persevered through elaborate roast dinners during Christmases where the temperature, if you were lucky, was one hundred degrees in the shade (in the old money). That group of Australians — variously represented by Germaine Greer, Christina Stead, Clive James and Errol Flynn — were faced with the choice of staying in Australia and remaining in obscurity, or going elsewhere to live and work in a cultural and intellectual milieu that was far more sophisticated overseas than in Australia. They carved out what has become a tradition: The Great Australian Pilgrimage To Anywhere But Here.

But by the end of the twentieth century, our culture had grown wide enough in scope and depth that it could encompass high ambitions. The decision to leave became a different kind of choice. Electing to spend some time living in London or New York, for most people in most fields, became something that might be a nice thing to do, but it wasn’t a referendum on your dedication to your profession. But the topography of choice is different for people trying to carve out spaces for themselves in creative industries – writers, actors, musicians and artists.

When Australian artists or writers take off, there’s often a very simple explanation: we’re going where the centre of production is. There are more publications, more galleries, and more theatres in the UK and the US. Australia is a small place, people-wise, in comparison to other countries, and there isn’t a huge audience or a lot of funding to go around for even the most established artists.

But there is something else involved in this choice, a kind of narrative that pervades the air in Australia like light, or sound. It’s the unspoken belief that some of us feel deeper in our marrow than others. It’s that to make it at home, you first have to make it somewhere else.

Many Australian writers, artists and musicians who leave both to work and study are doing so to effectively legitimise their practice. Sam Twyford Moore, who wrote an excellent explanation of this phenomenon, described how an artist friend of his had started “getting calls from galleries and curators only once his plane took off from Sydney en route to Berlin — that he had somehow showed some extra commitment by relocating, even though his work had not necessarily changed in shape nor form.”

Click through for the legend of Nick Cave, and the Australian cultural cringe.