Microsoft’s Age-Guessing Robot Reveals How Much Youth Still Matters

So you gave your face to a robot. Why did we just put our insecurities ahead of our privacy?

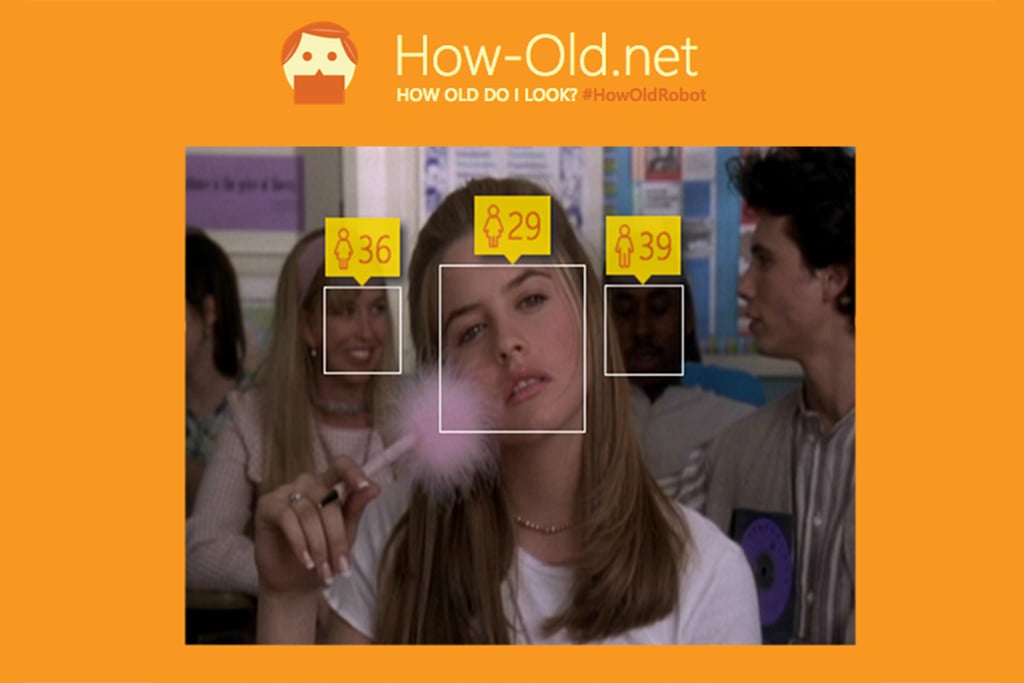

Yesterday, we awoke to the news that there was now a Microsoft robot offering to guess our age. Upload a photo of someone to the How-Old.net website and it detects how old that person looks — and the person’s perceived gender — with varying levels of accuracy.

You have chosen…..Poorly pic.twitter.com/Cnfk27sYy5

— Michael J. Roddan (@MichaelRoddan) May 1, 2015

Microsoft’s Machine Learning engineers took just a day to knock the site together, and then emailed several hundred people about it, expecting perhaps 50 to test it. Instead, it went viral. Very quickly, How-Old.net became a meme to troll public figures, make political commentary, and promote a movie in which Blake Lively stays the same age for decades.

But the speed and scale of the reactions reveal more than a nifty software trick. They show that scrutinising faces for their age — or, more accurately, youth — is still a major way in which we navigate the world and decide on other people’s worth.

–

Did Any Of Us Think About Where Our Face Was Going?

The How-Old.net website is interesting because of the way it leverages our insecurity about how we appear to others to promote Microsoft’s Azure suite of cloud-hosted software for business.

Basically, Azure is a marketplace for application programming interfaces (APIs) — data analysis software components, hosted online, which businesses and data scientists can buy, modify and combine for whatever best suits their purposes. How-Old.net combines several different Azure APIs and is a great demonstration of the modular way they work.

The facial recognition component, developed by Project Oxford, an initiative of Bing and Microsoft Research, analyses the photo and suggests the age and gender. The site also uses the Bing Search API, Event Hubs to collect the data, Azure Stream Analytics to process it, and PowerBI to generate a real-time dashboard display of the data. The website also collects the latitude and longitude from where your pics are being uploaded, and the platforms used to upload them, in an attempt to “observe virality in real time”.

As I’ve noted before in relation to online pop-culture quizzes, we’re drawn to submit to these totally arbitrary assessments by a promise of self-insight that we can then share with our friends. But the organisations administering the quizzes are the ones that benefit from that virality, in terms of mad clixxx and data collection.

And what is Microsoft doing with this information? Basically, whatever they want. If you uploaded a particularly flattering pic, it could even feature in the next Microsoft ad campaign.

fyi this is what you agree to by uploading your photo to http://t.co/c7P3zyJFNz pic.twitter.com/Upy00Qncmq

— Brandon Wall (@Walldo) April 30, 2015

We’re interacting with the website as if it’s just a bit of inconsequential fun, but what uses could it serve that we don’t anticipate?

Skynet monitors response to #HowOldRobot and rethinks strategy; sends back a cadre of sassy bots to subtly sabotage human self-esteem.

— John Bailey (@johnbonbailey) May 1, 2015

Not that I want to be a conspiracist or a doomsayer, but there is considerable reason to be concerned by the amount of data we willingly give away, which governments and corporations retain for their own purposes.

Just this week, an online study of US Spotify users has pinpointed the age at which we stop being interested in new music — 33. Our every click is contributing to a culture of banality, where Big Data offers us only what we’ve previously liked. Our data reveals us in embarrassing detail — but the human impulses that drive our action lie in between those data points. We might like to think we’re not limited by our age; but we’re already circumscribed by our clicks.

And despite intergenerational moral panics about teens oversharing online, younger internet users are actually reluctant to provide TMI. According to a new Essential Report, younger people are far more proactive when it comes to internet privacy measures. For instance, people aged 18-34 are vastly more likely (66 percent) than those over 55 (29 percent) to delete things they’ve previously posted, to use a fake or untraceable name online (51 percent versus 23 percent) and to use a VPN (22 percent versus 5 percent).

–

But We Still Judge People’s Worth By Their Age

Of course, the popularity of How-Old.net isn’t just about what the shadowy ‘They’ do with the age suggested by the website; it’s about what we do with it. How does our understanding of our own age, and that of others, colour the ways we interact online?

A WEB APP TOLD ME I LOOK OLDER THAN I AM SO NOW I HAVE TO SEARCH FOR MY SELF ESTEEM AT THE BOTTOM OF THIS TUB OF ICE CREAM STOP CRYING ADAM

— Adam Liaw (@adamliaw) May 1, 2015

We live in a youth-centric culture that doesn’t value experience, knowledge and prudence nearly as much as innocence, beauty and energy. We grant more attention, respect and authority to those whom we perceive to be youthful. Even the fact that I blame the baby boomers for infecting the entirety of Western culture with their generation’s fetish for youth is also quite ageist, I suppose.

In such a culture, people who struggle to preserve or regain the physical appearance of youth risk attracting only scorn and ridicule. We know the clichés in our ageing bones: grotesque cosmetic surgery and hair transplants; sports cars, leather jackets and leathery cleavage; May-December relationships.

On the internet, we scrutinise people’s faces, just as this website does. And we’re just as inaccurate, just as often. We’re obsessed with the age or agelessness of faces, admiring celebrities who look youthful without appearing to work at it, while damning those whose hard work is too visible. And as Amy Schumer has delightfully skewered, women bear the brunt of Hollywood ageism, while men are superannuated action heroes who merely quip about their advanced age.

Conversely, our culture praises youthful high achievers, from Mozart and Doogie Howser to cute child actors and and 26-year-old filmmaking prodigies. But it’s unfair to regard people as resources for supercharged human capital, and make them believe that if they don’t deliver great things on their ‘talent’ and ‘potential’, they’re disappointing society, not just themselves.

For as long as I can remember I’ve been paranoid about wanting to be young in my field. Aged 14, I frantically tried to write a novel, because I’d read about someone else who published a novel at age 15, and I wanted to beat her. I grew morose brooding about how I was becoming too old to be a prodigy. And I chose a three-year university course because I dreaded the thought of being ‘behind’ my peers by the time I entered my profession. (Of course, I went on to spend a total of eight years at university.)

Now, I’m sad about the ‘young writer’ prizes I can’t win and festivals I can’t attend, and the ‘30 Under 30’ lists I’ll never make.

@BooktotheFuture haha, pretty sure the #VogelsAward judges wouldn't be consulting #howoldrobot to assess entries!

— Allen & Unwin (@AllenAndUnwin) May 1, 2015

I make my living in a virtual space where I compete for attention and respect with people who are much younger than me. And I constantly feel I need to hide my age so that people will be fooled into thinking I’ve achieved more in my life than I have. So you can imagine the sense of joy and vindication with which I greeted my own assessment on How-Old.net.

AWWWW YEAAAAAH FOUNTAIN OF YOOF M8 pic.twitter.com/k3TeSWcHHL

— Mel Campbell (@incrediblemelk) May 1, 2015

That’s how the kids do it, right?

–

Mel Campbell is a freelance journalist and cultural critic. She founded online pop culture magazine The Enthusiast, and is the author of the book Out of Shape: Debunking Myths about Fashion and Fit. She blogs on style, history and culture at Footpath Zeitgeist and tweets at @incrediblemelk.