The Australian Music Industry’s #MeToo Moment Is Here, But Can It Last?

The #MeToo floodgates have opened in the Australian music industry in the wake of some explosive allegations - but the barriers to real change remain stronger than ever.

On Friday, July 10, Brisbane artist Jaguar Jonze posted three pictures across her social media.

— Content warning: This article discusses sexual harassment. —

They each contained a post-it note, upon which Jonze — real name Deena Lynch — had written a statement in her neat handwriting.

“It is sad that in my time in the industry, I’ve come across many predators who still abuse their place of power or profile and manipulate the trust people, especially young female musicians, have given to them,” the first note read. “In the last few days, I’ve been hearing so many stories about a particular male photographer who works in the industry.”

“When I was sexually assaulted last year by two producers, I felt alone, ashamed and didn’t know what to do, or where to go,” the second note continued. “I am just writing this to say, that if you have been affected by a similar story and need a safe space to land in this sometimes terrifying industry — please reach out to me.”

On the last note, she wrote that she wanted fans to know she was here for them, that she didn’t want this to happen to anyone else. “Stay safe and assert your boundaries,” she signed off.

But that wasn’t the end of it. Soon, Lynch began to receive messages from other women who claimed to have had similar experiences with the “particular” male photographer mentioned, as well as other unrelated incidents of harassment and misconduct in the music industry. In less than 24 hours, she says, she received stories from 20 women.

“I honestly didn’t realise the gravity of what I had unearthed,” Lynch told Music Junkee. “I’d just heard about this one particular story and obviously it touched more than a couple of women…but it was a really staggering, an alarming amount of women that needed to talk about it and needed to have it addressed, to no longer feel that they were the only ones.”

“I was so shocked at 20, but then it grew,” she continued. “Twenty was just the start of what I was going to unearth, and that in itself blows my mind — because 20 in itself is such a staggering number.”

“I honestly didn’t realise the gravity of what I had unearthed.”

Lynch began sharing these anonymous accounts across her socials, using the same post-it note aesthetic of her original post. The stories, which apparently regarded that same photographer, were disturbing — allegations of harassment, indecent exposure, coercion, unsolicited nude photos sent in messages, and more.

“In the first day people were just sharing things like ‘Oh I felt uncomfortable too, this is what he said to me, I felt he really crossed my boundaries’, but then as time went on the stories just got darker,” Lynch says. “I did that initial post not to call out, but just to hold space — but it became apparent to me that I needed to call it out further. But carefully, around defamation laws. I had no intention on creating the storm it’s created, because I don’t have that presence at all. The reason it’s taken momentum and has grown legs is because of the damage he’s done, and that’s the gross part.”

On Monday, the unnamed photographer at the centre of the furore outed himself. Jack Stafford, who often worked under the username re:_stacks, confirmed to The Sydney Morning Herald that he was the subject of the allegations. Stafford also published a 3000-word apology on Medium, in which he called himself “an abuser” and admitted to exposing himself and initiating uncomfortable and explicit conversations with his clients.

“When the stories first started coming I wanted to dismiss so many of them due to the context they were being portrayed in,” he wrote. “And it appears everyone whos [sic] maybe ever encountered me has a story about something I’ve said or done that was not okay to say or do. I accept that my whole makeup was inappropriate, that my personality was not okay, that even the little things matter, every off joke or statement or moment, every photo, everything, wrong.”

Stafford wrote that he has “shared things that were not mine to share” under the “cover” of art, but he claims he “never did this in a derogatory way”. “Regardless this wasn’t and never is okay, the women in my life who I know, who I’ve worked with, they are sisters, mothers, friends, wives, partners, they need protecting from men like me and I have failed that,” he wrote. “When any woman is hurt by a man, all women are hurt by men.”

“I abused my power. And have displayed pure misogyny in more than just my professional career but also in my personal life,” he continued, before stating that he would never work in the industry again, and that he wouldn’t be seeking legal advice for potential defamation proceedings at this time. “While I’m sure with some shifty manipulative bullshit lawyer I could claim defamation in some of these instances, I absolutely will not go down that path if I don’t have to. I want people to know that,” Stafford wrote.

For Lynch, the apology simply wasn’t good enough.

“He starts off the statement saying ‘I shouldn’t have responded in my stories or whatever, that I should have been listening more’ [Stafford originally responded to the allegations via Instagram] but he goes on to write a 3000 word apology that goes in all directions, that has a thinly veiled threat in there, that victim blames,” she says. “I felt like it really didn’t take into account the gravity of all the damage he’s inflicted onto all of these women. Considering the stories I now have, I know the reality is a lot more disgusting than what he touches on. I think that apology just simply does not cut it at all, or address the trauma he’s inflicted upon these women.”

In a statement to Music Junkee regarding the above comment from Lynch, Stafford wrote that he is “doing my best to learn from this” and is “getting help in many directions”.

“I’ve never meant to cause anyone harm and I’m trying to take accountability for things I deem to be true that are being said about me,” he told Music Junkee. “Though some of these things and/or the context is not entirely true. This has absolutely ruined my life and a lot of people won’t sympathise with that. I’ve not at all had the intent to victim blame and I’m sorry if that’s what I did I’m absolutely learning.

“My ‘threat’ was truly trying to be the opposite of such too. I feel so much of this is intent vs outcome and I’m learning very quickly all at once the power and presence of my being and words. I am not entirely sure what Jonez has been told, and it appears everyone who’s ever met me is now recounting every bad joke or odd thing I’ve said or done and remembering it in a new light. I take this all very seriously and I am truly sorry for the people I’ve hurt.”

Stafford’s full response is at the bottom of this article.

The allegations against Stafford opened the floodgates, and Lynch says she has received “hundreds” of stories from women across the music industry who have encountered harassment and misconduct.

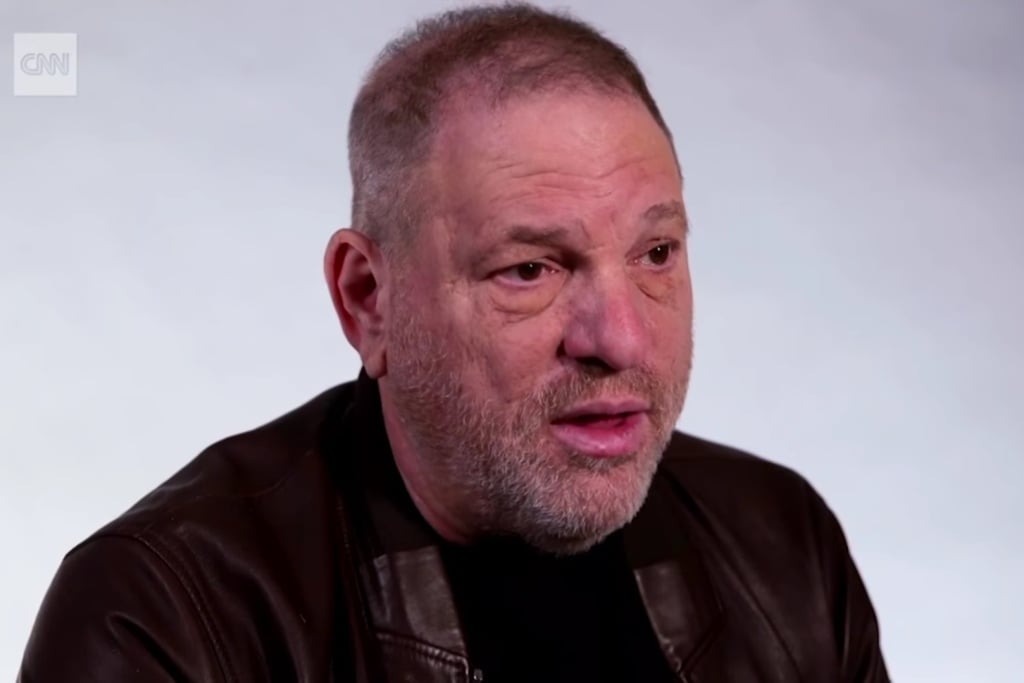

It’s the first real wave of #MeToo allegations to hit the Australian music industry since the movement exploded in 2017 following the downfall of Harvey Weinstein, who was convicted by a New York jury in March 2020 of five criminal sexual charges brought against him. The conviction was a momentous victory — nearly three years after allegations of sexual assault and misconduct were published by The New York Times and The New Yorker, some justice had been served.

The Pulitzer Prize-winning articles in the Times and New Yorker — written by Jodi Kantor, Megan Twohey, and Ronan Farrow, respectively — cracked open one of the biggest social movements in modern history. The shockwaves reached far and wide: public figures like Kevin Spacey, Louis C.K., and Matt Lauer experienced spectacular falls from grace after serious allegations were made against them (although, as in the case of Louis C.K., some have since returned to the public sphere). In the music world, #MuteRKelly began to trend worldwide, forcing Sony Music to drop Kelly from the roster — he’s now facing serious criminal charges.

But in Australia, the movement has been almost non-existent. Don Burke was publicly disgraced after allegations of sexual harassment surfaced in November 2017, but managed to evade any serious consequences — two years later, he successfully sued one of his accusers of defamation. In a now notorious case, Geoffrey Rush was accused of behaving inappropriately towards fellow actor Eryn Jean Norvill during a production of King Lear in 2015. Rush then successfully sued The Daily Telegraph, who published a series of articles about the alleged incident.

In the Australian music industry, the impact has been even less. It’s not that the stories aren’t there — they very clearly are — it’s that the tight-knit nature of the local music industry, and the defamation laws in Australia, are hamstringing any attempts to bring perpetrators to justice.

Defamation, Australia, And #MeToo

The legal concept of defamation is fairly straightforward: basically, if you say anything publicly about someone that lowers their reputation in the eyes of other people, that’s defamation. If the subject is exposed to ‘hatred, ridicule, or contempt’ by comments that you have made, they can sue you for defamation. And in Australia, the bar for what counts as defamation is extremely low.

“Australia is known for being a plaintiff-friendly jurisdiction,” Hannah Marshall, from Sydney’s Marque Lawyers, told Music Junkee. “There are bigger hurdles in places like the UK and the USA which reduce the number of defamation actions there. Just the other day a guy in Perth won $6500 in a defamation action over text messages sent by one acquaintance to another. That illustrates the low bar for actions in Australia.”

“Our plaintiff-friendly defamation laws have effectively killed the #MeToo movement in Australia.”

Laws surrounding defamation are meant to balance protecting personal interests with larger public concerns around free speech and communication, and Marshall doesn’t think Australia is currently getting that balance right.

“Defendants, commonly news publishers and in the case of #MeToo, survivors, have an unreasonably difficult time defending their claims,” she says. “That’s one of the reasons that Australia is viewed as a plaintiff-friendly jurisdiction. It’s also one of the reasons that the #MeToo movement hasn’t had more success here.”

In the US, for instance, the Bill of Rights protects free speech, which makes it more difficult to raise a claim of defamation. In the UK, the plaintiff must prove that ‘serious harm’ was caused by the defamation — that caveat doesn’t exist in Australia. Marshall also points out that stronger protections for publishers are available in the UK and US, making it easier for them to report serious allegations.

“Our plaintiff-friendly defamation laws have effectively killed the #MeToo movement in Australia,” she says. “The Geoffrey Rush case is a prime example of that. There have been no major complaints made since that case.

“Defamation actions allow those accused of sexual misbehaviour to turn the tables back on the complainant, forcing them to prove the truth of their claims in order to defend the action. In many #MeToo cases, the evidence boils down to one person’s word against another’s. The Daily Telegraph’s defence in Rush hinged on whether the judge believed Eryn Jean Norvill’s testimony. He didn’t; and Rush won.”

“I feel really sick that I have all this knowledge and I can’t do much about it…It allows this behaviour to go on hidden, or secretly, or be swept under the rug.”

Publishers that report a #MeToo story in Australia face a massive legal risk. “The cost/benefit analysis for most news publishers, especially after Rush, just doesn’t stack up,” Marshall says. “And for a survivor wanting to tell their story, the emotional cost is exorbitant. Their credibility is judged in a forum ill-suited to the complexity of sexual harassment and assault claims.”

Last year, as part a wide-ranging piece written by Gina Rushton for BuzzFeed News, I outlined some of the problems that publishers like Junkee Media face when trying to report on allegations of misconduct in the music industry. The financial risk for small publishers like Junkee, in most cases, is simply too great — and the lawyers are always waiting to pounce. I told Rushton of one particular case in which we received legal threats before we had even published a story (after publishing we received more serious correspondence) and how music journalists had received letters from lawyers regarding tweets they had written which didn’t even mention the name of the artist or artists involved in certain, much-whispered about, allegations.

“I feel really sick that I have all this knowledge and I can’t do much about it,” Lynch tells me when I ask her opinion on Australia’s defamation laws. “I feel really sick that I’m not able to call it out or tell people…whether that’s younger people entering the industry that don’t know these stories, or people who are placed in vulnerable situations where that kind of foresight would have altered their course entirely. That makes me feel really sick. It allows this behaviour to go on hidden, or secretly, or be swept under the rug — and it makes it quite difficult for me to do what I’d like to do as a person…to protect people.”

Don’t Dog The Boys, Or Dare To Speak Up

Australia’s music industry, compared to that of the UK and US, is very, very small. It doesn’t take long to get to know nearly everyone, and life in the industry is a constant series of parties and alcohol-fuelled events where you’ll bump into them. It’s an atmosphere that makes it very difficult to call out bad behaviour — no one wants to piss someone off only to run into them at a show next week; no one wants to risk harm to their career by talking about someone’s friend. As such, serious allegations are swept under the carpet, the only airtime they receive is being whispered about in tight-knit industry circles.

“There are a large amount of stories from within the Australian music industry that have almost become myth, because they stretch back so far,” music journalist Sosefina Fuamoli told Music Junkee. “They’ll come up in conversations at a BIGSOUND [music industry conference] or at a festival, but there haven’t been many stories taken public to the point where the perpetrator has been named and targeted.”

“I can remember different conversations I would be involved in, or even be privy to, with high powered individuals that would be so inappropriate.”

Fuamoli has noticed changes in industry attitudes over the last few years regarding equality and diversity, but she flags that there’s a lot of work to be done.

“I can remember different conversations I would be involved in, or even be privy to, with high powered individuals that would be so inappropriate, that I didn’t feel comfortable in confronting at the time because I was young and easily disposable in their eyes,” she says. “I think about the people who have been taken advantage of and abused and can only imagine how isolated and lonely it would feel.

“Personally, I’ve not had any experiences of sexual assault or harassment within the industry, though I do know people who have, who have been reluctant to come forward because ‘X knows Y and Y books Z event, and I can’t lose my job’, for example. There is still a reality for many people who work in music here that they won’t have the protection of those at higher levels, and that really needs to change.”

If you’re a man in the music industry, take @JaguarJonze’s actions as a big hint that you need to do better. Back your non-make colleagues. Call out problematic behaviour. Use your power and privilege to speak up. Create safe spaces where these discussions can be had.

— Abby Butler (@abbzbutler) July 12, 2020

And when allegations do get aired, she says, the reaction from those in power is to hush it up as much as possible to avoid it damaging reputations.

“I’m noticing more nowadays that whenever there is a sniff of an allegation surrounding an individual, they’re more likely to be cast out from the flock under another guise,” she says. “They’ve moved on from this project, they’ve been let go from this company…it goes on. Sometimes I don’t even think it’s about ‘protecting the boys’, moreover it’s about protecting assets — like ‘If I run a label and one of my staff has had allegations surrounding them, I’m letting them go not to protect them from public scrutiny, but to protect my brand’.”

“It’s a small industry, so word gets around quick if there’s been enough chat about it,” Lynch says. “But at the same time I’ve also seen it go the other way — it almost seems like the industry protects the perpetrators. It’s such a small pond, and there’s a power structure in that pond, and we don’t want to be upset or be outcasts from that small playing field.”

“I know what it feels like to find the courage to speak up, and not get the level of acknowledgement or empathy or understanding or care.”

Lynch sounds nothing short of exhausted on the phone during our conversation, and admits she’s feeling overwhelmed by the events of the last few days. “It’s just really hit me now. I think I’ve put up a wall over the last few days to just hold space, to listen to every single story, and to give the same amount of energy to every single person who has come forward,” she says, after a long pause. “Because I know what it feels like to find the courage to speak up, and not get the level of acknowledgement or empathy or understanding or care. I know the absence of that can do a lot of damage in the healing process for someone and I don’t want to be a part of that damage.

“I was on my phone all day every day, hardly sleeping, making sure I get to every single one of [the stories]. And that took me to this moment, talking to you, when I’ve realised that it’s…a lot. And it’s really sad, and I feel a little hopeless, because what are the next steps?”

Lynch is right: the way forward is unclear. Clearly, publishers and media outlets need to be allowed to pursue allegations without the constant fear of retribution and financial ruin — and that won’t happen without a serious reconfiguration of current laws. But also, equally, change within the industry itself is desperately needed, and that can only be enforced by the people in positions of power.

“This isn’t an issue that will be fixed by offering more grants or spots on a bill for women and non-binary artists,” Fuamoli says. “If anything, the past year has shown that women/non-binary people in the music industry will not be placated. Systemic change is key.”

Jules LeFevre is the editor of Music Junkee. She is on Twitter.

— Response from Jack Stafford —

I’m doing my best to learn from this and getting help in many directions. I’ve never meant to cause anyone harm and I’m trying to take accountability for things I deem to be true that are being said about me. Though some of these things and or the context is not entirely true. This has absolutely ruined my life and a lot of people won’t sympathise with that. I’ve not at all had the intent to victim blame and I’m sorry if that’s what I did I’m absolutely learning. My “threat” was truly trying to be the opposite of such too. I feel so much of this is intent vs outcome and I’m learning very quickly all at once the power and presence of my being and words.

I am not entirely sure what Jonez [sic] has been told, and it appears everyone who’s ever met me is now recounting every bad joke or odd thing I’ve said or done and remembering it in a new light. I take this all very seriously and I am truly sorry for the people I’ve hurt, Though again I’ve seen things being said about me that are not true. But the sentiment that I need to change is very true, and there are things that are very very not okay, I’ve engaged in multiple therapy sessions which are helping my mental health just. This and a few legal discussions of which I am choosing not to act on. I want other men to be watching this. Again I’ve never ever meant to hurt people but I absolutely understand that I have.

I know my character is being absolutely torn to shreds and no one stands by me and I understand. I really just want it to be clear how sorry I am and how prepared I am to take true accountability whenever and wherever I can. The sheer number of stories breaks my heart that I have made that many people feel uncomfortable around me, it’s truly killing me to think about and I am going to continue to reach out to the people who I can to better understand how they feel and listen to them, and apologise and work on every detail inside of my make up.

I’ve been made out as someone with no feeling, and that isn’t true, it’s no excuse to say for the most part I had no idea this is the experience I was giving people but I more than know now, I hope some people out there remember me as kind and someone who’s always been open to change and that I still am that person willing to change, I am changing.