What It Means To Love ‘Lion’ As A Third Culture Australian

"I wanted so badly to belong, instead of eternally straddling two countries, two cultures."

Lion might not have won any of the six Oscars for which it was nominated, but it certainly won viewers’ hearts. I’ve seen it twice, and each time the cinema melted into a deluge of tears — men, women, over-caffeinated film critics, it didn’t matter. The film has even waltzed past the likes of Strictly Ballroom to become one of the top 10 highest-grossing films in Australia. It’s an astonishing success, to match an astonishing tale.

If you’re one of the five people who haven’t seen Lion yet, it follows the true story of Saroo Brierley. As a child, Saroo fell asleep on a decommissioned train that carried him more than 1,600 kilometres away from everything he had ever known. He wound up in a Calcutta orphanage, from which he was adopted by a Tasmanian couple. Then, 25 years later, he found his birth family through a combination of exhausting diligence and the then-fledgling Google Earth technology.

Lion, the film adaptation of Brierley’s autobiography, feels like an antidote to the whitewashed shows that populate local television screens, and a palatable version of the modern migrant experience in this era of painfully calcified immigration policy. It’s a gift for third-culture kids, on an eternal quest to find out where they belong.

Identity and Anzac Biscuits

Lion is far more than Brierley’s search for his family — it’s the tale of a young man’s hunt for his identity, his struggle to reconcile his past in India with his present in Australia. I interviewed Brierley for The Weekly Review earlier this year, and we spoke at length about the profound melancholy of being between two worlds and none. He instantly knew what I was talking about; it was far and away his longest response, and you could see him tense up from the barrage of memories. This portion didn’t make it into that interview, but he absolutely nailed an experience endemic to so many third-culture children.

“Here you are in reality, and all of sudden you have that juxtaposition where you’re lost in nostalgia, being in India and going through that hardship,” he said. “Some people, especially my friends, would notice that I wasn’t with it — I was there, I was listening, but I was also in another world trying to understand what [the memories] meant, because it was affecting me so much. Not to the point where I felt the need to express it or tell anyone — it was a jigsaw puzzle that had to be reconfigured and populated before I could extract it and put it together.”

I love that answer. Not just the languid, waking-dream quality of it, but that last line — on one level, he knew just how far away he was from an answer to who he was, because he was still in the process of forming the question. But his struggle went even deeper than that, into the guilty second-guessing that can accompany this sort of self-interrogation: why do I feel this way? Where is home, really? And will this ever stop?

I’ve asked myself those questions my whole life. I have an Australian mother and a Malaysian father; she met him on a tropical stopover on her way to visit the UK, and he spent many of his early pay cheques calling her long-distance. During this period, he had a neat afro, clip-on earrings, and a propensity to order Coke instead of alcohol in bars. My mother laughs about this, until I point out that it was a combination effective enough for her to stay in Malaysia for three more decades.

My maternal grandmother lived with us for most of that time, and she and my mother provided many of our core stories and treats: compilations of poetry by Henry Lawson and Banjo Patterson, magnificent plum puddings every Christmas, and a complete set of Footrot Flats (technically from New Zealand, yes, but required reading for anyone with farmers in the family).

It might sound surreal to think of Anzac biscuits cooling in a sticky Kuala Lumpur kitchen, but it was perfectly normal for my brother and me. Malaysia is not without its problems, but it is a beautifully multicultural place to have a childhood. I have seen every Young and Dangerous film, still count some Malay songs among my favourites, and once donned my gran’s old cycling cap to recite Mulga Bill’s Bicycle to an utterly bemused school assembly. But which of these experiences were mine, really? It’s hard to describe the feeling — so much bliss, persistently haunted by the notion that I was a tourist in the country where I was born.

Adding Up The Separate Parts

Looking back, the things that are especially bizarre are the memories of white privilege, of being a brown kid given special treatment because of the colour of his mother’s skin. In primary school, prefects would pull me out of line during assembly because I was all sweaty from playing football during recess, which was expressly forbidden; I’d be let off because it was the curse of my inherited genes to perspire in a tropical climate. I’d go to the shops with my mother, and the shopkeepers would be sunshine and happiness; but show up with my dad, and I’d be shadowed down every aisle.

This chasm grew wider as my brother and I got older. When we were teenagers, he said something to me that I’ll never forget: “No matter where we go in the world, we’re going to be minorities”. It made me disconsolately lonely then; even now I feel like I can’t fit the full impact of that statement into my skull. I wanted so badly to belong completely to something, instead of eternally straddling two countries, two cultures. I wanted to fit in, just for once.

In Australia, it didn’t matter how much culture we’d absorbed, or how much we thought we fit in — our names and our hybrid accents set us apart. As children in Queensland, passersby would compliment our mother on our tans. As adults in Melbourne, the colour of our skin was just another way to be different.

In 2012, I took a job at a newspaper in Beijing. For the first time in my life, I didn’t feel like I had to maintain the high-wire act of proving my authenticity to myself and everyone else. I was completely foreign, and it was complete freedom. The euphoria lasted until the end of my contract, when I decided to do some travelling. When I flew in to the USA from London, the immigration officer couldn’t comprehend how the four young women ahead of me in the queue — all of whom had Tamil names — were actually English nationals. They were reluctantly allowed through, but my face and name in combination with an Australian passport proved entirely too suspicious. I missed my connecting flight as the questions about my background grew more and more incredulous, but I could empathise with the misgivings. Most days I have them too.

Watching Lion felt like a revelation. Saroo Brierley’s circumstances are vastly different from mine, but I was dumbstruck by the way the film lingered on his discomfiture, and how eerily familiar that discomfiture felt. It wasn’t just that he felt he didn’t belong — he didn’t know if the separate parts of him could ever add up into something whole. It’s a torment endured by so many migrants and so many children of migrants the world over: this queasy, lurching suspicion that someday someone is going to find out just how disconnected you feel and expose you for the utter fraud you are.

A Story About Bridging The Gulf

On repeat viewings, it’s the way Lion is constructed that makes it enduringly special. It spends half its running time on Brierley’s childhood, with the tremendous Sunny Pawar acting his little heart out. He’s born into utter poverty, but it’s a joyous time in his life, and the film paints it as such. He has so much to do and see, so many adventures with his elder brother, so much love from his mother.

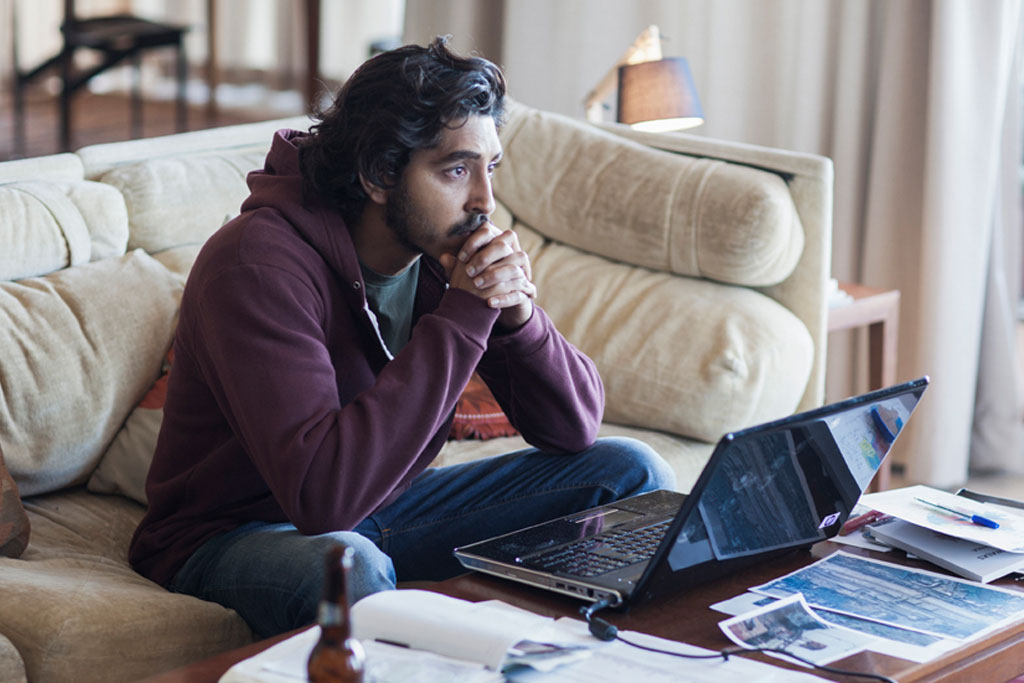

When we first meet adult Saroo, as played by Dev Patel, the Australian iconography is complete. He’s got the accent (courtesy of MasterChef, of course), the surfboard, the Melbourne sharehouse packed with uni friends. Instead of mining the gulf between these stages in his life for pathos, Lion does something far more special: it counts both as equally valid, never intimating that one is lesser or that one should be sacrificed to boost the other.

It’s a bold move, to look so tenderly at an upbringing so far removed from these shores, and count it as part of the Australian experience because it was experienced by an Australian. Quite apart from the horrific treatment of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, it is the tragedy of immigrant nations to keep revisiting the cycle of violence and intolerance upon each successive wave of immigration. Lion’s going to cure racism in Australia as much as the Obama administration cured racism in the USA, but it’s heartening to see this story embraced as much as it has been. Never mind that it hasn’t even been 50 years since the end of the White Australia Policy; it hasn’t even been a decade since so many Indian students were bashed in Melbourne that it became an international incident.

Sure, Lion is a film written and directed by white Australians, and you get the feeling that Brierley’s adoption by white parents helps makes it palatable to some. But there’s a reason Lion has been as successful overseas as it has been in Australia — it’s the messy, heartbreaking, joyous tale of a human being. It’s so well-made, so well-acted, that it’s hard not to empathise with the on-screen Saroo Brierley. And it’s hard not to appreciate where he is now, in person.

“I’m a product of my mum and dad, and my adoptive parents, but I also have a mind of my own,” he told me. “I want to create an identity of my own.” He’s looking forward, choosing his own adventure, and that’s a beautiful thing.

—

Hari Raj has worked as a journalist and editor in Malaysia, China, and Australia. He tweets about pop-culture ephemera at @jarirah.