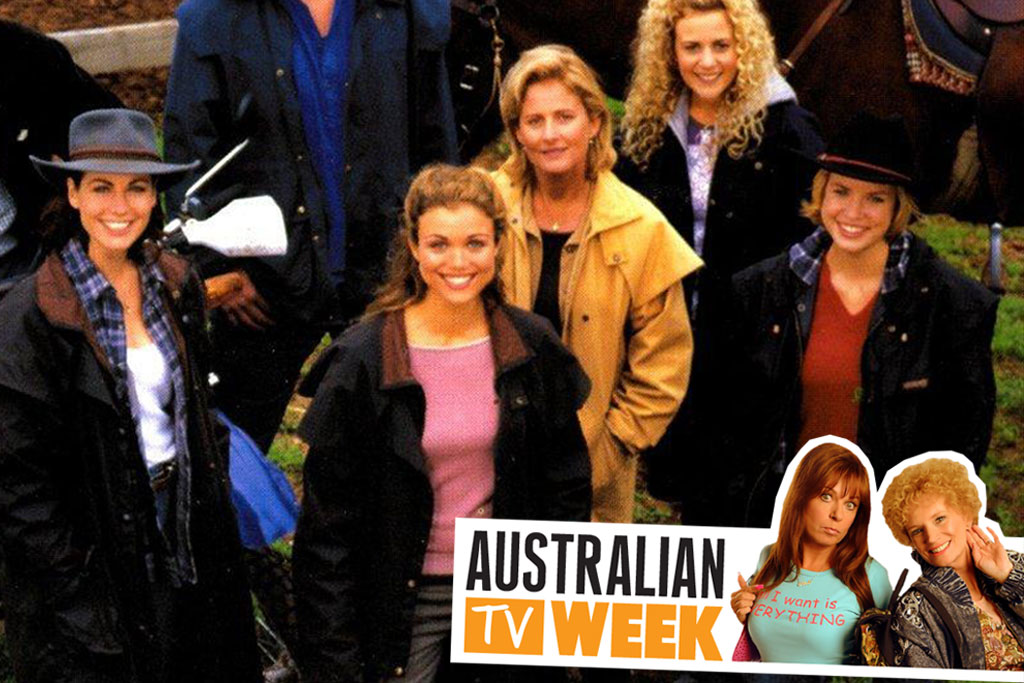

‘McLeod’s Daughters’ And Feeling Real Grief About Fake TV Deaths

I was embarrassed to be so obviously affected by something that I knew logically, had never even happened.

This week we’re celebrating the very best of Australian TV. You can check out our list of The 60 Greatest Australian TV Shows Of All Time right here.

–

I remember watching the television in horror, curled up in the corner of our old green couch in my nightie, unable to look away even though I wanted to very badly. I remember feeling the complete and utter weight of this tragedy as though it had happened to a relative, not a made-up character. Even though I knew that what I was watching wasn’t real, I was feeling very real feelings — and a lot of them. I held back tears, embarrassed to be so obviously affected by something that I knew logically, had never even happened.

I was ten years old, navigating the peak of my horse-crazy phase, and completely obsessed with any media available to me that might quench my thirst for equine representation. The Australian series McLeod’s Daughters, set on a large cattle farm in the Australian outback called Drover’s Run, and based around the lives of two half-sisters Claire and Tess (played by Lisa Chappell and Bridie Carter), fit my criteria perfectly.

On this particular night, Tess, Claire, and Claire’s baby Charlotte were driving their ute out on the Drover’s Run property, on their way to gather supplies for a party. Suddenly, as these things always go, Claire had to swerve the vehicle to avoid a wild stallion, and the ute ended up balancing precariously on the edge of a cliff. What follows is a nail-biting scene in which Tess slowly removes herself and the baby from the car — but cannot manage to release Claire, whose leg is trapped beneath the steering wheel. Claire tells Tess to look after Charlotte, and the car topples violently over the edge of the cliff.

The death of a television character is a memorable, confusing, and often traumatic experience for a young person to go through for the first time. And it’s not surprising – a child can barely grasp the concept of death itself, but pair this with the fact that they must try to understand that fiction ≠ reality and you’ve got yourself one bewildering, emotionally bitter cocktail.

Having just consumed this cocktail for the very first time, I was fixated; I couldn’t stop picturing Claire’s partner Alex abseiling down the cliff and discovering her (realistic) corpse. I couldn’t stop feeling sorry for Alex, who had — conveniently — planned to propose to Claire just that evening. I couldn’t stop worrying about Charlotte’s future and how Tess could possibly go on with the guilt of surviving the accident that killed her sister.

Not a single audience member wants to witness the intense, overwhelming suffering that, in reality, would occur after an accident like the one that resulted in Claire’s death. We watch television as a form of escapism, not as a reminder of the horrific things that life can present to us. We crave the drama in short bursts, we love to feel and cry — but not too much! Too little, and we don’t care about the characters or anything that happens to them. Too much, and we are too reminded of the suffering that we inevitably, painfully have to endure in our own lives — and we turn away.

“Death has always been a potent element of storytelling,” writes Debra Oswald, co-creator and head writer of the Australian series Offspring. Indeed, the shock death of Patrick Reid, beloved beau of main character Nina Proudman and father of her unborn child, was met with genuine grief, disbelief and even anger from fans of the show. Demands for an explanation were made across social media in the aftermath of the episode entitled ‘Goodbye Patrick’. Monumental plot moments such as these always split audiences and generate controversy, for better or for worse.

Dramatic television is mostly just a contrived adaption of the most exciting bits of real life. Claire and Patrick’s deaths were constructed to evoke serious emotion from the audience. Having done this so successfully (McLeod’s Daughters was the most popular drama program on Australian television in 2003, and the most recent season of Offspring garnered an average rating of 1.027 million viewers per episode) there really was no need to show the true ramifications of the real and prolonged grief that these characters would have suffered.

And as such, I recall that the characters in McLeod’s Daughters moved on from this tragic event quickly, and new characters were introduced to fill in the gaps and bring a refreshing light-heartedness to the farm. Similarly, in the wake of Patrick’s death Nina Proudman had an unborn child to birth, and save for a few heart-wrenching moments in the following episodes where she was visited by Patrick’s ghost, her life continued as well.

I wish that I had allowed myself to just feel the feelings that Claire’s death provoked in my little heart. Instead, I was embarrassed and confused by them. I was so convinced that because Claire was a work of fiction, my grief was redundant, even foolish. I wish I had understood that it’s so common, and so okay, to love a character so much so that you mourn their loss.

That old saying ‘it is better to have loved and lost, than to have never loved at all’ sums it up, really. Allow yourself to fully love your characters while you still can – before they get squashed by a tree branch, fall into a grain silo, or just simply fake their own death to throw off the hitmen on their tail.

–

Eilish Gilligan is a musician and freelance writer from Melbourne, Australia. She loves all things pop culture and tweets at @eilishgilligan.