We Asked The “No” Campaign Who Religious People Should Be Allowed To Discriminate Against

If people should be able to refuse same-sex couples, should they be able to refuse interracial couples?

If you’ve been following the marriage equality debate at all, you’ll know that one of the key arguments of the No campaign surrounds “religious freedom”. The campaign often talks about a hypothetical Christian baker or florist, who might be forced to service a same-sex wedding against their genuinely held religious beliefs.

It’s an argument that opens up a whole lot of other questions.

“Genuinely held religious beliefs” are a deeply personal thing, and can vary from person to person, and faith to faith. For example, there are some Christians out there who might still think that an interracial couple shouldn’t be allowed to marry.

There might be a baker who doesn’t like Jewish people, or perhaps a chauffeur who hates Muslims. Should they be allowed to refuse to work for the wedding of a Jew to a Muslim?

And how far do these “religious freedom” protections go? If the baker and the florist can say no, can a printer refuse to print the invitations? Can a cabbie refuse to pick up guests after a long night of drinking and dancing at their friends’ wedding? (this question has actually been asked before).

If you can refuse to serve a same-sex wedding, what else can you refuse to do? Can you kick a couple out of your business for holding hands? Can you hang a “gays not welcome” sign in your front window, just to avoid any awkwardness?

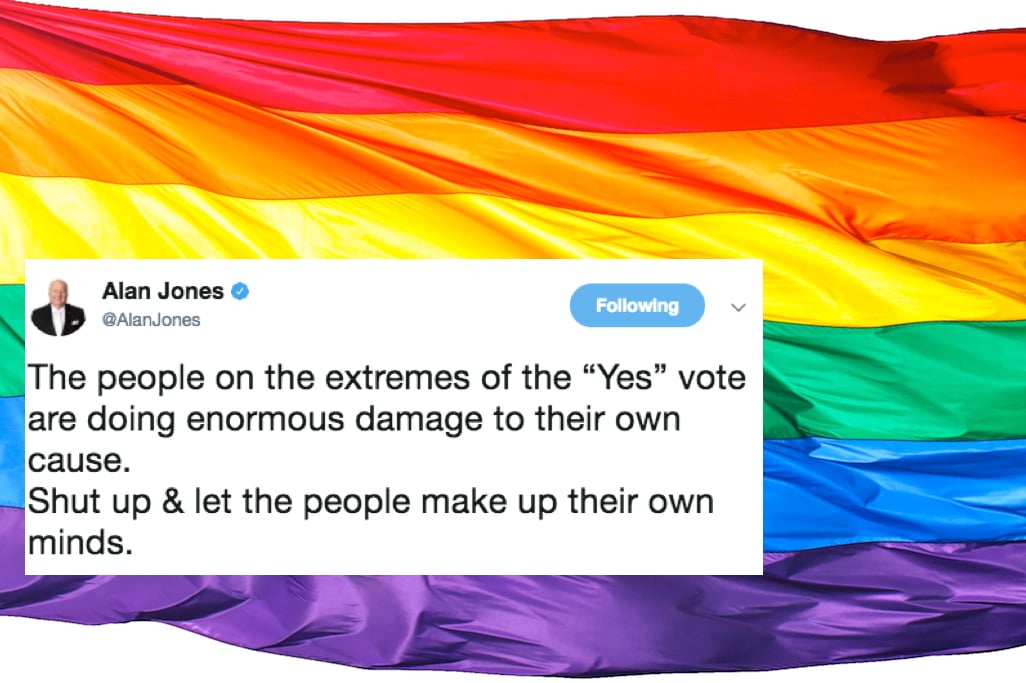

Lyle Shelton from ACL says ‘homophobia doesn’t exist much in Australia’ at National Press Club MORE: https://t.co/aJVd793yvc pic.twitter.com/IlKWlcBFWX

— Sky News Australia (@SkyNewsAust) September 13, 2017

Is This Really The Australia The No Campaign Wants To Live In?

I asked the official No campaign about this last week. Here’s the answer they gave, in full:

“Freedom of speech and religion should be extended to all Australians, not just to members of the clergy. In countries where marriage has been redefined, the consequences for expressing traditional views on marriage have become more serious.

“People have been kicked out of university courses, fired, denied business or employment or forced to resign for saying what they think, and those who have chosen not to participate in same-sex weddings have been fined or dragged through the courts to answer bigotry charges.

“In this campaign already, we have seen advertising and creative agencies make public pledges to not work with our campaign. Although disappointing, we respect their right to decline to use their creative talents to share a message with which they disagree, and we believe this right should be extended to all Australians.”

So no specific answer on the hypothetical interracial/Jewish/Muslim couples about which I asked.

But Today They Couldn’t Avoid It

In their televised address to the National Press Club on Wednesday afternoon, two of the leading No campaigners, Lyle Shelton from the Australian Christian Lobby and Liberal Party vice-president Karina Okotel, were directly asked about all this.

Here’s the question, asked by Herald Sun journalist James Campbell, and their answers, which we’ve slightly edited for clarity.

Campbell: “Just following on from your point about religious protections. If Parliament were to enact a law which granted [a baker] the right to refuse to bake a cake for a gay wedding, would those… what would stop someone, say an orthodox Jew, refusing to bake a cake for a Jew/non-Jew marriage? Or someone who had a religious objection with an interracial couple from making use of the law to protect, basically to exercise their prejudices?

Would such a law, for example, allow hotels to refuse to rent rooms to gay people or interracial couples or mixed religious couples if that was the religious objection of the own? How would you stop someone taking that law and taking it to that extreme?”

Lyle Shelton: “Well, it’s a hypothetical. But it is a fair question. I think people… we’re told that there’s no consequences to changing the definition of marriage, that people’s freedoms won’t be affected but I think you won’t be allowed to believe what you believe about marriage now, and for that to be the same, if it changes. Particularly if you want to live that out publicly in your business or whatever.”

Campbell: “With all due respect, no small number of people hold the positions that I described. What would stop them utilising such a law?”

Shelton: “Well, I think you’d be talking about a law, hypothetically, that allowed people to continue to believe the same thing about marriage. It would be specific to that. I don’t think anyone is suggesting that there should be racial discrimination, I certainly wouldn’t be.”

good question from Herald Sun: what would stop exemptions allowing people to refuse inter-racial marriages? #npc #auspol

— Paul Karp (@Paul_Karp) September 13, 2017

What Shelton appears to be saying here is that while he would never want to see people discriminated against on the basis of race, and while he certainly would not want to see that, he believes it’s important for religious freedom to be protected.

He says he wouldn’t like to see people discriminated against, but he doesn’t say if it’s possible that it could happen in his ideal world, in which religious freedom is protected absolutely. Karina Okotel then gave a short response.

Okotel: “The issue, I suppose, is fundamentally about religious freedom and whether that is an important thing to protect or not. My view is that it is exceptionally important. If we lose that freedom, then what does that say about democracy and the country we live in?”

It’s still not really clear what the consequences of the No campaign’s vision of religious freedom would be.

So We Called Shelton

Shortly after speaking at the NPC, Junkee gave Shelton a call to clarify his position.

He iterated that under no circumstances would he want to see a world in which racism was entrenched in legislation. He’d like to see religious freedom legislation that pertains specifically to freedom around weddings and its attendant industries.

“If it’s based on race, I don’t think that’s right,” Shelton said. “By virtue of the fact that you’re asking that question, it shows that there’s a lot of uncertainty around this.”

But when Junkee put it to Shelton that his version of Christianity might not be the same as someone else’s vision of Christianity, and that under his proposal, both versions of Christianity might be protected by the same religious freedom laws, he said it would be up to someone else to argue where the line should be drawn.

“They’ll have to go and lobby for those. I don’t think the parliament would go and facilitate those sort of things,” he said. “That’s not for me to decide. You’d have to ask the parliament and the legislators, [but] that’s absolutely not one of the consequences I’d like to see.”

¯\_(ツ)_/¯