Analysing MangoGate: How A Year 12 Facebook Group Became Ground Zero For Harassment And Abuse

It's the weirdest online maelstrom I've been involved in.

“You’re a lil bitch. Suck ma mango dick.”

Over the past 24 hours I’ve been bombarded on social media by scores of angry teens furious about mangoes, culminating in the above message sent to me on Facebook. It’s not the first online maelstrom I’ve been involved in, but it’s definitely the weirdest.

This story has its roots in something very specific: a high school English exam. But how did a two-mark question about a poem evolve into memes attacking a young Indigenous writer, racist and sexist abuse, alleged death threats aimed at the meme creators, identity fraud and the targeting of journalists reporting on a Facebook group?

The answer is messy and complicated but it says plenty about the state of online discourse and the intersection of banter and meme culture.

Mangoes And Memes

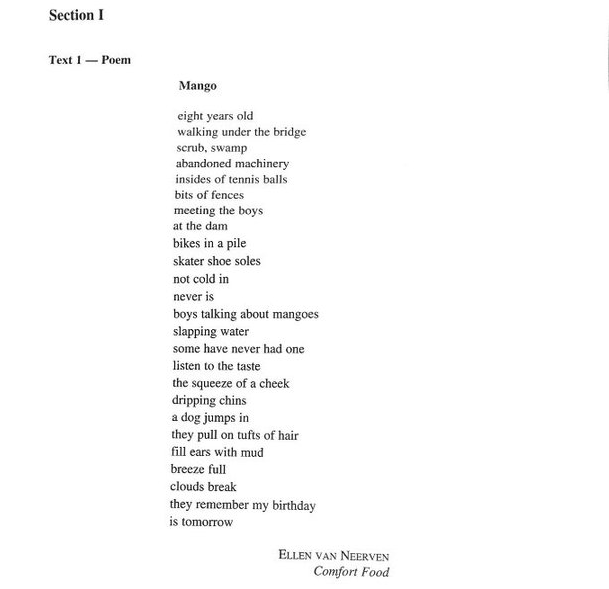

This week tens of thousands of Year 12 students in NSW began sitting their final year exams. The first paper, as per tradition, is the English exam. This year’s exam featured a question, worth two marks, that invited students to respond to a short poem by award-winning poet Ellen van Neerven titled Mango.

Some students struggled to understand the poem or found the question (“Explain how the poem conveys the delight of discovery”) too vague. After the exam, posts and memes making fun of the poem soon began popping up on High School Certificate (HSC) discussion Facebook groups. The biggest group, ‘HSC Discussion Group’, has nearly 70,000 members.

The first posts about the English exam mainly consisted of innocuous pictures of mangoes with captions like “WTF”, inviting fellow students to express their frustration about the poem. But people soon began posting pictures of van Neerven (who wasn’t even aware beforehand that her poem had been included in the exam), shifting the focus of the student’s angst onto her personally. One of the first comments about van Neerven read “hope u choke on a mango”.

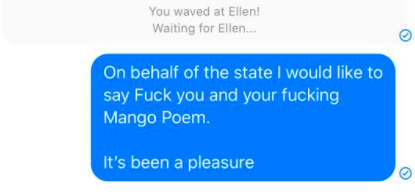

Some members of the group began messaging van Neerven on Facebook and sharing images of the chat. One message read “On behalf of the state I would like to say fuck you and your fucking Mango Poem”. The post received more than 300 ‘Like’, ‘Haha’ and ‘Love’ reacts, and comments like “bitch deserves it”.

After that the floodgates were open. Van Neerven received dozens of abusive messages on Facebook, she was harassed on Twitter by angry students and her Wikipedia page was defaced so many times admins were eventually forced to lock it and prevent further edits.

When van Neerven’s friends attempted to defend her on Twitter, and asked students to stop harassing her, they themselves became targets of abuse. One was called a “stupid Muslim”. Another had her picture posted in the HSC Discussion Group with sexist and derogatory comments discussing her physical appearance. Some received personal messages from students encouraging them to kill themselves.

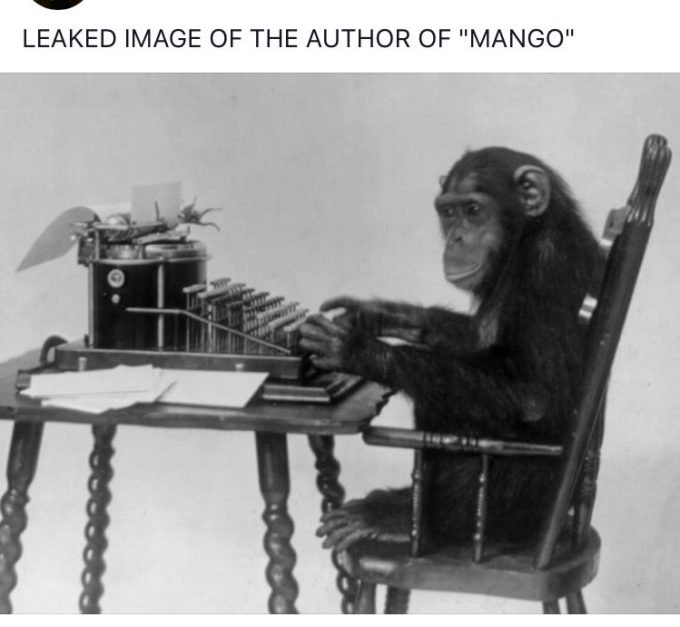

On Twitter a number of Indigenous friends and colleagues of van Neerven shared posts from within the group they found racist, including a picture of a monkey and a typewriter with the caption “Leaked image of the author of ‘Mango‘“. The image became a key focus of subsequent media reporting on the issue.

In a statement provided to Junkee, the creator of that image denied being motivated by racism and said he wasn’t aware of van Neerven’s Indigenous background when he posted it. He said he had received death threats in response to the coverage and accused the media of “vilifying someone who had made a harmless joke”. He said he felt “violated” that people had taken screenshots of his post that included his name and shared them onto a news website.

In a statement provided to Junkee, the creator of that image denied being motivated by racism and said he wasn’t aware of van Neerven’s Indigenous background when he posted it. He said he had received death threats in response to the coverage and accused the media of “vilifying someone who had made a harmless joke”. He said he felt “violated” that people had taken screenshots of his post that included his name and shared them onto a news website.

The HSC Discussion Group was an open group, viewable by anyone with a Facebook account, until yesterday afternoon when it became closed. All the memes, images and posts made in the group were viewable by anyone, including journalists.

Regardless of the intent of the monkey image, the group was populated by posts and comments targeting van Neerven’s race, including a parody of Black Lives Matter and references to her as a “coon” and “abo”. Similar derogatory and racist comments were posted about the people defending van Neerven on Twitter, a large proportion of whom were Indigenous and people of colour.

The Media Covers The Story

The first outlet to cover the issue was The Sydney Morning Herald. The story, and those published by other outlets, were posted into the group and received a mixed response. Some students were upset that the memes and posts they had created (which they perceived as “harmless jokes”) had turned into a national media story. Others bragged about how they had made headlines (“We should be proud. No other HSC year made it into the news for MEMES”).

Some compared it to a 2016 incident when journalist Rachel Corbett wrote about the previous year’s group for News.com.au and focused on the proliferation of abusive memes targeting specific individuals and trolling. Corbett herself became the target of violent and sexist abuse by members of the group after publishing her story.

“Is it too early to crown Ellen van Neerven as 2017’s Rachel Corbett?” one student wrote this week.

After I wrote a story covering the issue and the abuse van Neerven and others had received, I began receiving dozens of tweets and direct messages from students in the group. The messages consisted either of more abuse or earnest defences of the group, arguing that most of the posts weren’t racist or sexist, and the ones that were weren’t representative of the whole group.

A blog post written by a student defending the group argued that the posts directed at van Neerven were a form of literary criticism “albeit completely non-constructive and served rather as pieces to chuckle over in light of our exam.” Many students contacted me to explain that the creation of memes was a form of stress relief designed to take some of the pressure off in a difficult exam period.

While I didn’t find the explanations entirely satisfying — the process of systematically harassing a poet because you didn’t understand or appreciate their work is difficult to defend — I was interested in finding out more about what drove the students to make the posts in the first place, and then defend the group’s behaviour.

The Students Speak Out

After conducting more than 20 interviews with students in the group, including those who admitted to harassing van Neerven and those who called out the behaviour, an interesting tension began to emerge.

Some students viewed the group, despite its huge size and public setting, as a kind of safe space for “kids” to vent about the HSC. While they didn’t condone racist and sexist abuse specifically, they didn’t see anything wrong with students making fun of van Neerven or messaging her.

However other students told me they found the culture toxic and aggressive and expressed dismay at how members of the group were egging each other on to harass van Neerven and her defenders.

“I believe it was taken extremely out of context,” one student told me, referring to the image of the monkey. “[Students were] attempting to vent their frustration that they are unable to understand and comprehend the meaning of the poem, as if it was written by something that did not know what they were doing.”

“On behalf of the dumbasses in my grade, I want to apologise for this disgusting behaviour,” another said. “I wanted to thank you for calling the perpetrators out and highlighting this isn’t just abuse — but racially targeted hate speech.”

“These memes were created for a laugh, or how our year group would say, ‘for the lols’.”

Most of the students I spoke to clearly identified strongly with the HSC Discussion Group, and tried to draw a line between its culture and the instances of abuse.

“The fact that race has been brought into it is simply disgusting and 70,000 people are being condemned for it,” one student told me. “I realise the group itself is a massive platform and is public, so yes people should have been aware that some of the memes and jokes were ridiculous and not funny at all. However most I have seen were innocent and were poking a bit of fun.”

“These memes were created for a laugh or how our year group would say ‘for the lols’,” Cindy, 18, said. “However the negative aspect of this group is that there are a select few who take advantage of the opportunity for their own attention that is why there are completely absurd or nonsensical posts made by students and the abusive and racial comments that have been seen by many already.”

One of the students who privately messaged van Neerven told me he had apologised to her, explaining that he was “just stressed out”.

“At the end of the day we are just a bunch of 17 and 18-year-olds who were trying to make light of a situation,” he said. “On behalf of the state I would just like to say that we are truly sorry for any ill feelings, we may have caused Ms Ellen van Neerven”

However, other students told me that they believed the group had a more serious cultural problem that saw abuse go unchecked, and even encouraged.

“I felt during the first maybe half hour the memes simply referencing a mango were harmless but unwarranted, however they begun to spiral out of control,” Caitlin, 18, said. “I have to be honest I wasn’t surprised jokes included suicide references as that is something our cohort has been involved with over the past two years where suicide was referenced jokingly, which is appalling.

“I strongly believe this cohort has a tendency to bully.”

Another student told me that the abuse was the final straw that had prompted them to leave the page. “I’ve been seeing ‘vote no’ [to marriage equality] memes on the page for months but I just shrugged it off as a small, vocal minority being crappy on an average discussion group,” they said.

“But after seeing torrents and torrents of abuse aimed towards writers — some of whose work I had read and respected — I had to stop contributing to the crap on that page. I’m sending this privately because, although I pride myself as relatively outspoken, I’m terrified of being abused relentlessly if I dare speak badly about the page publicly.”

This Isn’t Over

Despite the critical media coverage and the defences offered up by some students, members of the HSC Discussion Group continue to create and share memes and posts targeting van Neerven and those who came to her defence.

There are also a number of examples where students have posted the social media accounts of journalists they believe reported the story incorrectly, with appeals for members of the group to harass them.

In a bizarre twist, some members of group began creating fake tweets and posts designed to incite further attacks on those who support van Neerven publicly. A fake tweet purporting to be sent from the account of an Indigenous woman read “Someone should give these white HSC students what they deserve, I would be SO happy if these stupid white cunts fucking died. Can someone please do it. #BlackTwitter #IStandWithEllen #KillThem”.

I DIDNT POST THE FAKE TWEET. I have a 140 character limit and DO NOT WISH DEATH ON YOUTH. pic.twitter.com/yXBhm1hCug

— ?️?beckgwen?️? (@ChewbeckaSolo) October 17, 2017

The fake tweet was sent to journalists, including me, by dozens of students as an example of how they were being threatened by van Neerven’s friends and supporters. More fake tweets allegedly from van Neerven’s account were also concocted and shared.

A number of Indigenous women on Twitter have been forced to lock their accounts in response to the non-stop harassment.

Why Should We Care About Any Of This?

There are two seperate, but overlapping, processes that help explain how a Facebook discussion group ostensibly about bonding over final year exams devolved into a organising space used to co-ordinate harassment, identify and target victims and celebrate abuse.

The first has to do with the nature of online discourse, and a lack of understanding of the consequences of certain kinds of online behaviour.

Clearly many students felt as though the Facebook group, despite its large size, was ‘their’ space where they could vent about all sorts of topics, including a confusing question in the English exam. Most of the students I spoke to were shocked at the idea that members of the public, along with the media, would care about the proliferation of abusive posts. Some were at pains to point that out of the 70,000 members “only” an estimated 1,000 had contributed to the harassment directed at Ellen.

“We just like our memes and banter,” one popular post in the group reads.

The focus many students placed on the “majority” of the group not taking part in racist and sexist abuse misses the bigger issue. In pointing out that the group has facilitated and helped provide a space to co-ordinate a sustained (and growing) chorus of harassment, the argument isn’t that every single member within it is a terrible person or a racist. The question is more about whether there is something within the group’s culture, or the way certain speech is promoted and policed, that encourages a particular kind of aggressive behaviour.

The vicious targeting of Corbett last year should have been a warning that something was fundamentally broken within these groups. The episode, along with the recent attacks on van Neerven and others, suggests that there are a core of returning members who are happy to use the group to organise these kinds of campaigns of harassment. In fact, some of the members who encouraged the abuse of van Neerven are the same people who signed and shared petitions calling for Corbett to be “banned from the internet”.

It’s telling that the response from the group’s admins to the recent controversy wasn’t to discipline those who were racist, sexist or abusive, or to call for members to respect the advertised rule to “be respectful”, but instead to change the group’s setting from ‘open’ to ‘closed’. They made it slightly more difficult for the public to see what was going on inside.

There still doesn’t seem be an acceptance of the fact that launching a tidal wave of harassment against a poet was a wildly inappropriate move.

While it’s true that a small number of commenters actually called out the personal attacks, the general mood within the group was to encourage them by sharing and posting examples of abuse and harassment and rewarding the ‘funniest’ ones by showering them with likes and positive comments. Even though group members feel victimised by the media coverage it wasn’t until the stories began to be published that students began to pull back on the direct abuse of van Neerven — though memes and posts attacking her are still being shared.

Despite the fact that the vast majority of members are using their real names, with profiles that link to their schools and workplaces, it seems like the students felt like they were cocooned from external consequences. They didn’t expect their comments would actually cause anyone distress, it was all just banter after all, and they certainly didn’t predict a national media firestorm.

But the students aren’t victims. They might be uncomfortable with the realisation that their posts were easily viewable by pretty much anyone, but Facebook groups — especially large ones — are not secret societies firewalled off from the rest of society. And even if they were, it was the students who broke that firewall by using the group to identify targets of harassment and then pursuing them on different platforms.

Even now, most of the students who have messaged me are more eager to defend the group than condemn the attacks on van Neerven. Leaving aside the specific disavowals of racism and sexism, there still doesn’t seem be an acceptance of the fact that launching a tidal wave of harassment against a poet was a wildly inappropriate move.

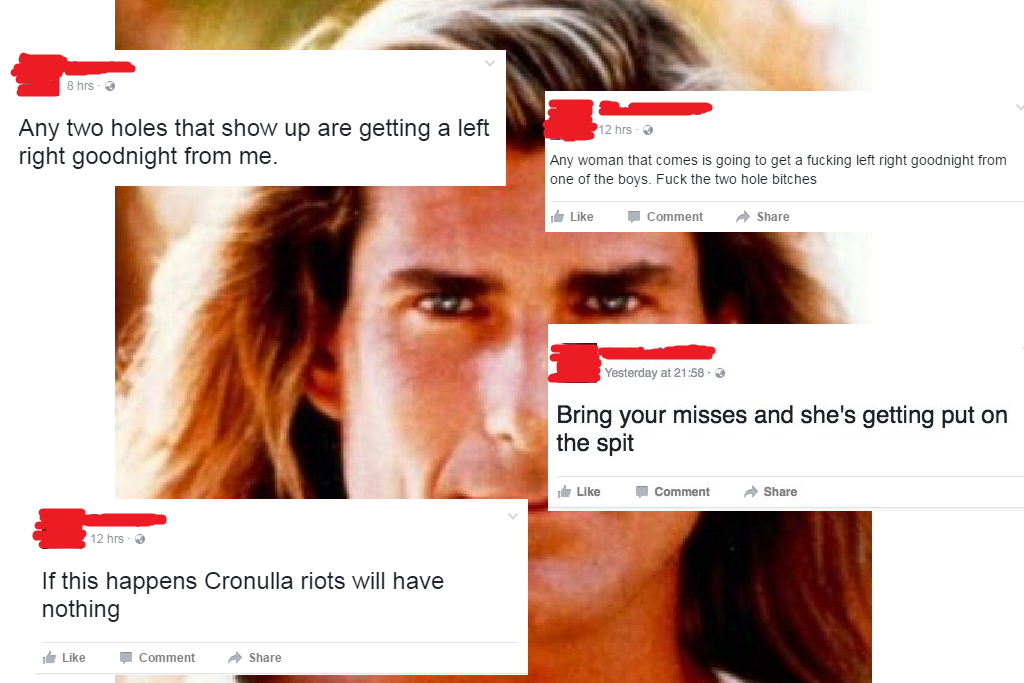

There are similarities to an incident with the ‘Yeah The Boys’ Facebook page last year. The group had been criticised for promoting a culture of violence towards women, and was ultimately shut down after supporters of page threatened to attack women calling them out. Like some of the students in the HSC discussion group, posters on Yeah The Boys didn’t seem to realise that their posts had real-life consequences for the targets of their abuse, and even though they were posting online, they weren’t anonymous. Regardless of the future of the HSC Discussion group, it’s a lesson some of the students might want to learn sooner rather than later.

The other thing to note about these kinds of groups is that even if participants think they’re operating in a bubble removed from the rest of society, they aren’t immune to the same structural processes that influence cultural responses and discourse, like, for example, sexism and racism.

It doesn’t matter how well-meaning some participants might be, a group the size of the HSC Discussion Group is going to replicate the same forms of oppression that exist in the rest of the world. Inevitably there will be racist and sexist language and there will be people who refuse to acknowledge it or excuse it as harmless “banter”.

Most of the students I spoke to seemed to believe that once they explained the monkey image wasn’t “intended” to be racist, the group should be absolved. Again, this misses the point. There were numerous examples of racist posts and memes. While the admins condoned them, some have now been deleted through Facebook’s notoriously inefficient and ineffective reporting process.

The question of whether the group facilitates harassment doesn’t rest on the motivations behind one image. Throughout this whole ordeal the main targets of the abuse have been people of colour, particularly Indigenous women. Now that might not have been a conscious decision on the part of the students, but it’s due to a set of norms they can’t remove themselves from.

This Isn’t Just About A Facebook Group

We know that women and people of colour experience a disproportionate amount of abuse online (and in the real world, for that matter). In this particular context, the additional targets of the abuse were also disproportionately women and people of colour.

Why? Because that’s how this stuff works. When people of colour face a wave of abuse it’s often other people of colour that come to their defence. In this instance it was overwhelmingly Indigenous women who fought the hardest to defend van Neerven, which made them targets of further abuse. One of the first groups to condemn the abuse and support van Neerven was the First Nations Australia Writers Alliance, though other writers’ groups have issued similar statements more recently.

The most vocal defenders of van Neerven, who had their posts and social media accounts shared in the group with comments encouraging further harassment were almost exclusively people of colour. The students can argue that they weren’t motivated explicitly by racism, but the argument doesn’t have much merit when an organised mob is systemically targeting a particular cohort.

It’s not exclusive to this group. It’s a reality of our society. But it’s something those who take part in ongoing campaigns — and those who continue to defend them — need to acknowledge.

So what happens next? There are calls for the Department of Education to intervene and discipline those responsible for the worst examples of abuse. I’m not convinced that appeals to that kind of bureaucracy will resolve the issue of students in these groups acting with a sort of nihilistic impunity for the lols and likes. However, the fact that this is likely to become a more common occurrence in the future may be cause for the NSW Education Standards Authority to reevaluate how they support writers whose work is included in exams.

The broader issue of sexism and racism isn’t something a Facebook group, or any online community, can fix on its own. It plagues society and we shouldn’t expect a community of 70,000 to be immune from it. But, like any community that purports to be a safe and respectable environment for everyone, it’s fair to ask how that sort of culture is being created and enforced.

If students see racism and sexism or instances of abuse and harassment they should condemn it and create a culture where that kind of behaviour is discouraged, rather than encouraged and supported under the guise of “memes and banter”. This doesn’t apply only to the HSC Discussion Group, but to all online spaces.

Hopefully we can take something away from this bizarre saga that’s already caused too much anguish to too many people.

–

Osman Faruqi is Junkee’s News and Politics Editor. He tweets at @oz_f.