What We Learned From Interviewing The Most Famous Interviewer In The World

#1: It can be a hard choice whether to take a cheese sandwich off a Nazi.

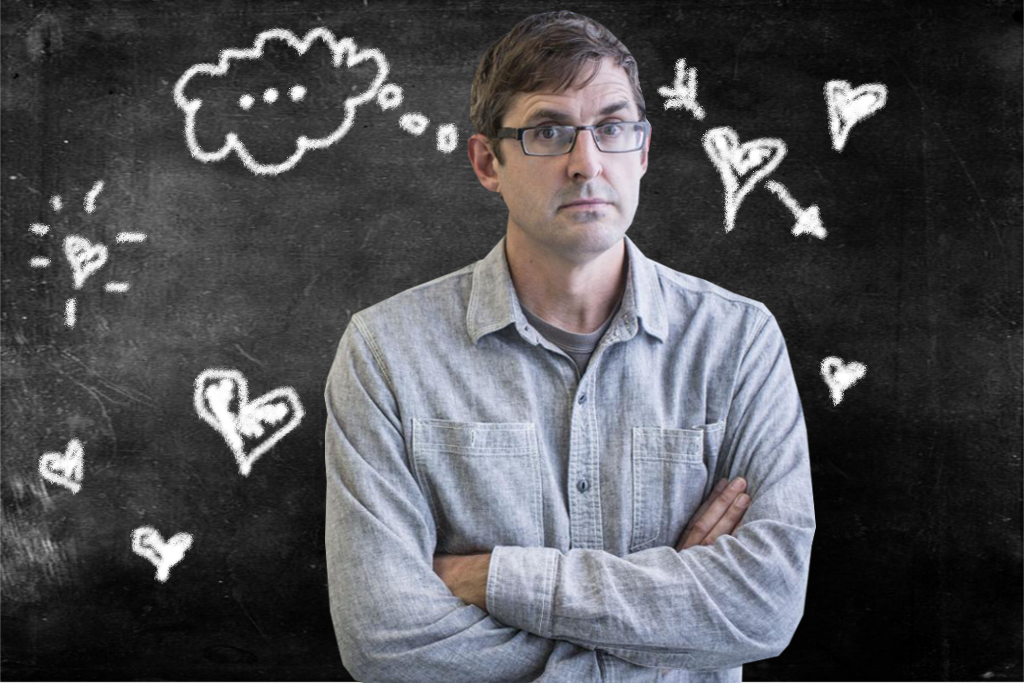

It’s strange talking to Louis Theroux, even over the phone.

Not because he’s gained international notoriety as a dogged documentarian, seeking out diverse and often controversial topics — or because of the phone delay. It’s because, after watching all of his Weird Weekends, his When Louis Met… series and his BBC specials, as well as his recent feature film My Scientology Movie, I feel as if I know Theroux quite well.

This is a feeling that’s persisted as I’ve followed his documentaries over the years, so much so that I wrote an embarrassing ode to him called “My Date With Louis” (*shudder*) on my university blog years ago. And it’s something I know many other fans can identify with because, when Theroux launches a documentary, he is so personable and genuine in his inquisitiveness, you feel as though he is your friend.

Of course, he’s not — he’s just an expert documentary filmmaker who has trouble understanding what publication I come from. “It sounded like you’re from Junkee,” he says when we’re finally connected via a spotty phone link. “Is that right?”

“I am from Junkee, yes.”

He pauses for a long time before asking, “What is Junkee?”

Theroux isn’t asking to be rude, he’s just being his naturally inquisitive self — he even tells me at the end of the interview that he’ll “look out for Junkee”. Which makes me even more nervous to interview him. How do you interview a famous interviewer?

Louis and Morality

Theroux is a deep thinker, and he answers every question I throw at him with a great deal of care after assuring me many times “That’s a great question”, like a friendly university tutor.

It’s easy to see how his personable nature might suck you in and make you safe if you’re one of his documentary subjects, many of whom might not be entirely comfortable being interviewed. Theroux often seeks out subjects that many would consider controversial, taboo, even fringe — though Theroux himself rejects this identifier when I quiz him on it.

“Fringe could be misunderstood, I suppose,” he muses. “You know, as humans, we’re quite weird creatures. And that’s maybe why I resist the term ‘fringe’ slightly. Because it’s as if we’re all fringe, we’re all grappling with the mysteries of our own psychology to do with human mortality, our urge to harm ourselves, our urge to harm others. Anger, hatred, tribalism, resentment, weird sexual impulses.

“We don’t want to just give carte blanche to groups that espouse hate.”

“And so if we’re honest, those impulses reside in all of us. So I try and choose subjects that will allow us almost to experience some of those vicariously, and also maybe create a little bit of understanding when you see how extreme these situations can be for other people.”

Extreme is a good way to describe some of Theroux’s more high-profile subjects, including a group of Neo-Nazis in California, Ultra Zionist nationalists in East Jerusalem, and the infamous US hate familial group the Westboro Baptist Church, about whom Theroux recorded two separate documentaries, The Most Hated Family In America and America’s Most Hated Family In Crisis.

While it’s fascinating — as well as a little sickening — to get an insight into these extreme institutions, I wonder if Theroux feels there is a danger in giving hateful ideologies a platform.

“You know, I think that’s a good thing to worry about,” Theroux tells me, characteristically careful in his response. “It’s a good thing to think about, and a good thing to be aware of, that we don’t want to just give carte blanche to groups that espouse hate, and put them on the airwaves without criticism and context.

“I think, for me there’s a couple of questions: and one is sort of about the level of power that they exercise, right? So with the Westboro Baptist Church, yes, they have a platform, they are known by millions of people around the world. But they are hated; no one needs to bring the news that the beliefs of the Westboro Baptist Church are hateful and wrong. It’s always good to be reminded, but I’m certainly not breaking the story where the Westboro Baptist Church are concerned.”

I feel he’s being a little too modest here. As an Australian, I didn’t register any news about Westboro before I saw Theroux’s documentaries (two of my favourites) on the subject.

Theroux clarifies again, “I think what is interesting is to sort of add a little colour and context to that, so you understand why people arrive at those positions. You attempt to understand the things that go along with that, which is breaking up of families, children being raised in a hateful atmosphere, people sort of sabotaging their own lives. And also some of the motivations that allow people to continue in those lives. The self-affirmation that comes from being in an embattled minority group.”

Louis Up Close and Personal

It’s interesting Theroux has mentioned this “self-affirmation”, because one of the things that makes his Westboro documentaries so compelling is how Theroux grapples onscreen with people. He is always on camera, often living, working and interacting with the subjects of his films, which is unusual as many documentary filmmakers prefer more observational filming methods.

“Partly it’s just a case of how I came to be doing the work that I do,” Theroux says. His first on-screen job was as a correspondent on Michael Moore’s television show, TV Nation. “I didn’t feel I was ever in a position to make documentaries in which I didn’t appear. I’d say, ‘I want to be a correspondent who is not on camera, who does sort of cinéma vérité segments.’ They would just be like, ‘Have you lost your mind? What do you think correspondent means?’

“Having started that way, I got into a habit of it. And it turned out that actually there’s real value in being on camera — hopefully not in a narcissistic way, but you can actually be present. Some of the situations are heightened for viewers because they have their guy they recognise.”

“Do you say, ‘No, take your cheese sandwich and shove it up your jacksy?’ Or do you say, ‘All right, but let’s talk about this Neo-Nazi thing?”

Theroux and I discuss one famous scene from his documentary Louis And The Nazis, where it appears Theroux might be in danger from a group of antagonistic skinheads who decide he is Jewish.

“There’s sort of a geeky guy from Britain with glasses, and he’s surrounded by Neo-Nazis who really don’t like the look of him, right? Suddenly you’ve got more drama, and much more strangeness. It all flows much more, becomes a much more interesting proposition.”

I ask Theroux if he feels his mission is in illuminating this “strangeness” to which he keeps referring. “I wouldn’t put it like that,” he says. “I think I would say that I am trying to almost create a sense of tension and conflict in the viewer by taking subjects and stories that take people to really extreme emotional territory, but from a position of identification or a position of empathy.”

He returns to the Neo-Nazis, asking me to imagine going among them and discovering some “human qualities”. “You sort of think, Well, that do I do with this? Someone I totally disagree with and they’re offering me a cheese sandwich and saying, ‘Sit down and put your feet up’. Do you say, ‘No, take your cheese sandwich and shove it up your jacksy?’ Or do you say, ‘All right, but let’s talk about this Neo-Nazi thing because it feels like a really bad idea’.”

I’m not sure I totally agree with him that these extreme ideologies need for us to recognise their “human qualities”. But Theroux insists that “You’ve got this strange sort of doubling: the way you act intellectually and the way you act emotionally. And it throws up all these interesting and rather troubling dilemmas.”

I ask Theroux whether it’s difficult to avoid becoming too involved with his subjects. “It is some,” he reflects. “It’s both difficult and also the whole point. I mean that’s the whole idea, to get close to the people who you may have seen on TV but not yet in a rounded human way.”

Theroux likes to think of it as “immersive journalism”, but with “an emotional immersion, and a feeling of intimacy”.

Louis’ Latest Project

One of Louis’ latest extremes is one that taps into a social phenomenon that Australians will find uncomfortably familiar — the drinking culture. Louis Theroux: Drinking To Oblivion analyses drinking culture, and what happens when it goes beyond what’s considered socially acceptable.

He is very enthusiastic when I mention Australia’s drinking culture, and tells me, “I drink probably more than I should, and I try to be open about that in the program, mentioning how much I drink and the way in which many of us, myself included, exceed government guidelines on how much you’re supposed to drink — which always seem to be unrealistically low, if I’m honest.

“I think I was interested in a drug that many, many people can consume legally, socially, as families, with friends, marking the most important moments of our lives. As always I was looking to take it to an extreme place, a place where it was life-threatening and beyond that, a place where it sabotages one’s entire set of relationships, pushes one’s friends and family away.”

He tells me his subjects in this film “are not drinking for pleasure, they are drinking almost to disappear, or to make everything disappear.”

But, of course, access does not guarantee results, so I ask Theroux how he works to open up his subjects once the access has been granted. “I try and be approachable, I try and be a pleasant and attentive interlocutor, you know, someone who’s talking to them and isn’t just there to make the program. You know, sometimes it’s about doing stuff off camera, just sort of building relationships and letting people know that you are interested in them, not just professionally but in a human way.”

He pauses again before concluding, rather modestly, “And that’s about it. You know, you stick around long enough and hopefully you’ll get the story.”

—

Louis Theroux: A Different Brain and Louis Theroux: Drinking To Oblivion are available to stream now on ABC iView. A portion of Theroux’s back catalogue is also available to stream on Stan.

—

Matilda Dixon-Smith is Junkee’s Staff Writer. She tweets at @mdixonsmith.

–

Love film and TV? We’re holding our inaugural Video Junkee festival in July, a new annual event for lovers and creators of online video. Video Junkee is on July 28 & 29 at Carriageworks in Sydney, featuring keynotes, masterclasses, screenings, interviews and more. Tickets are on sale now.