“This is a doughnut. It is very sweet, and very good. But if you’ve never tasted a doughnut you really wouldn’t know how sweet, and how good, a doughnut is… Transcendental meditation gives an experience much sweeter than the sweetness of this doughnut. It gives the experience of the sweetest nectar of life. As Maharishi says, those who don’t know, they don’t know. Those who know, they enjoy.”

– David Lynch, Meditation Creativity and Peace

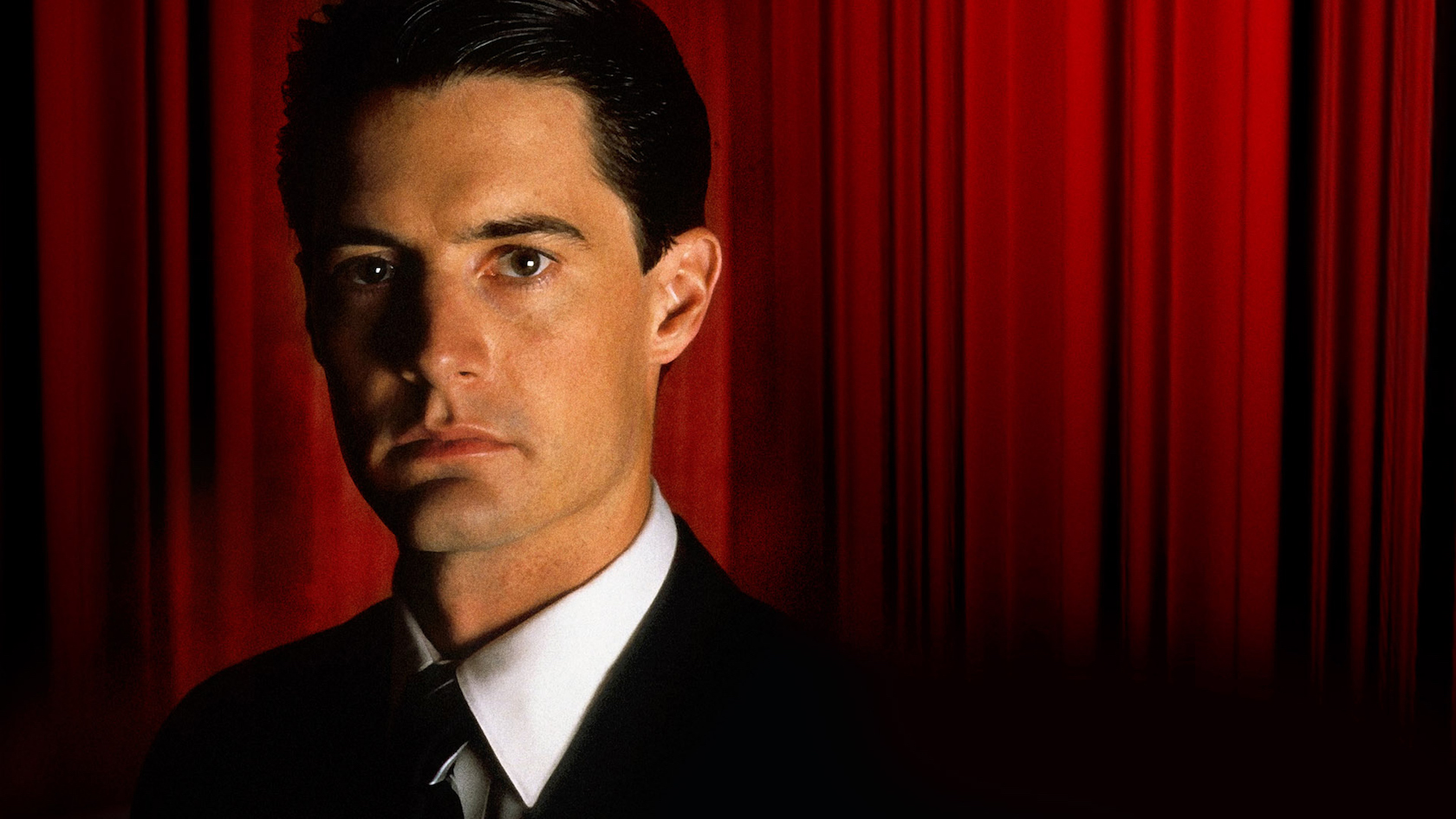

Three months ago, I began writing an article about watching Twin Peaks in the age of the hot take. I couldn’t bring myself to finish it. Every episode of the new season told me not to write it; that my hot take about the futility of hot takes regarding Twin Peaks was in itself futile. The further I fell into Twin Peaks: The Return, the truer this felt. I was Agent Cooper talking into a tape recorder, but there was no Diane on the receiving end.

David Lynch is the master of uncertainty — a currency greatly devalued in the time of the listicle, the call-out, and the recap. That uncertainty grabbed me from the start of the new season, but as it increased with the low thrumming sound of the show’s static soundscape, it touched something much deeper than a TV viewer’s desire to know ‘what’s next’.

The Return, I’ve come to realise, is a meditation. It’s structured like the koan poems and paintings of the Buddhist thinkers Lynch loves so much: blurring what we know, to reshape how we know. Within its circularity and declarative befuddlement is an enlightening deconstruction of prestige TV — what it is, how we watch it, and why.

At 17, Twin Peaks changed what I watch, and my way of watching it. It was a communal experience (with friends, swapping theories etc) which revolved around a show which simulated community. Every fan forms their own memories and spaces within the Twin Peaks they keep in their head. Over a quarter century of speculative fandom, our White and Black lodges may differ. So The Return takes the concept of nostalgia, personalises it, and eradicates it — or, if you meet it halfway — reconstructs it. In this typically Lynchian paradox, your experience is singular, familial, and universal.

The Return is, to paraphrase Major Briggs, a vision of light.

That gum you like is going to come back in style

People discuss the legacy of the original Twin Peaks as though it were a beloved high-schooler on a morgue slab. Critics use it as a garnish, measuring rod, and reference point in their quest to give the convulsive explosion of modern television some kind of linearity.

Vince Gilligan (Breaking Bad, Better Call Saul) and Noah Hawley (Fargo, Legion) often have their work compared to Lynch and Frost’s masterpiece. Stranger Things was touted as a Twin Peaks heir last year, because it revelled in nostalgia and anachronistic aesthetics. Twin Peaks, as a descriptor, came to signify ‘quirk’.

As Albert Rosenfield would say, that is the easy pigeonholing of dullards and dumbells. Twin Peaks isn’t a roadmap to weirdness but rather a hammer to the commodification of it, to the desire to sentimentalise it. Think less rose-tinted sunglasses, and more the off-kilter blue and red of Dr Jacoby.

To Lynch, time is not so much a flat circle, but rather, a sweet doughnut.

The Return is designed, like the meditative exercises that Lynch loves so much, to guide you to meaning via profundity. A roving monk amongst static dilettantes and would-be TV auteurs and parable spewing monologuists (hello, Fargo), Lynch dares us to ask if our reliance on ‘higher minded’, more critically-acclimatised television hasn’t bred a new and lethal form of passivity.

Lynch is a true surrealist in prestige TV’s bukkake storm of winking callbacks and Gen-X nostalgia: one with a visual memory and language heavily influenced by TP. A surrealist reduces, rebuilds, and readjusts a text, and therein makes the audience participant. Lynch couples this with eastern thought however, and applies the surrealists’ destructive force with the buddhists’ cyclical interiority to make us, the viewer, re-examine our sense of pace, structure, time itself.

To Lynch, time is not so much a flat circle, but rather, a sweet doughnut.

The original Twin Peaks achieved this in radical ways. David Lynch took 50 years of wholesome American TV watching — the day-time soap, the workplace sitcom, the murder mystery — and warped it. Twin Peaks took long-established television tropes and garnered them with a then-unseen otherness. The image of the nuclear American family decently huddled around the TV set was obliterated.

This continues in The Return which, like the first series, has Laura Palmer’s mother zonked out in front of the idiot box. The trappings of American familyhood are in the static-glare of a TV that was witness to molestation, rape, murder. It is the third, often forgotten, player in the show/creator relationship.

For Lynch, television is both an act of togetherness and atomisation, the dystopic hearth of the atomic age, cluttering our minds-eye with conflicting images of the other, the self, and the desired. It’s the medium in which American exceptionalism both rose and collapsed. The Return uses vivid black and white ‘50s sitcom-soap signifiers, and a harsh digital MacBook tactility in the show’s contemporary corporate sequences. The clash between the two speaks to Lynch’s grand perspective of television aestheticism and is purposeful about the meaning offered by each texture.

Twin Peaks riffs on this within the show by having several scenes of isolated or muted characters absently watching the in-universe soap, Invitation To Love. It binds the original characters, it connects edits, and it prophesies their own melodramatic arcs. Lynch suggests we speak a shared language, if only in isolation.

Twin Peaks was a multi-layered satire of the ‘way’ of television, and why we consume it. Your motivation for watching was ostensibly to discover “who killed Laura Palmer?” — that question was on billboards, commercials, magazine covers, SNL sketches — it was the hook. There’s a reason Laura’s body was found by clueless fisherman Pete Martell (Jack Nance) — he was standing in for us, the viewer, as perennial rube. Laura Palmer was the beautiful magician’s assistant, a misdirection, holding the audience’s gaze while Oz stood behind red drapes, cackling.

“That’s what you do in a town where a yellow light still means slow down, not speed up.”

The Return continues this philosophical satire of TV consumption. The way in which we devour and regurgitate media has shifted dramatically since the death of Laura Palmer, and Lynch isn’t unaware of Twin Peaks’ role in the binge-watch tradition.

Twin Peaks is a show whose younger fans (like myself) experienced it via DVD boxset and marathon sleepovers, excitedly asking “just what the heck will happen next?” between pots of coffee, pie, and cigarettes. But the original run’s tumultuous production schedule made it a show that sparked cravings, while not always fulfilling them. Due to Lynch and Frost’s conflict with the ABC, original fans were left waiting weeks, months, and eventually 25 years between answers.

Again, Twin Peaks strikes two discordant notes, impossibly screaming out to be consumed with the enthusiastic greed of a Renault brother on a coke bender, while working precisely because it is dolled out in a way as idiosyncratic as its content. Back then, it was the looming presence of cancellation and stalled production, now it’s the singularly odd modern experience of having to wait a week between episodes for a streamable show.

The absence of Twin Peaks — waiting for it — becomes a vital part of the show’s effectiveness. We are given time to decode, deconstruct, and decide, or time to do nothing but sit in wonder.

Twin Peaks stretched the pacing of soap-operas and crime procedurals beyond recognition. A steady drip of absurdism punctuated a rigid form that, by 1990, didn’t risk ratings for experimentation. The non-sequiturs and philosophical meanderings of Twin Peaks were designed to lead us off a path: the pace, the sound-mixing, the extended close-ups of swinging traffic lights were designed to create space between the viewer’s base drive for answers, and the humbling peace that follows the unanswerable.

Lynch has long been obsessed with the ‘shape’ of Western storytelling — the quadratic script structures of American film, and by extension, TV. When Lynch’s films follow seemingly familiar story arcs he formulates divergence with the eye and ear. His works ask us to experience the way in which we experience, by throwing us off kilter — be it by soundscape, costume, character, or startling imagery.

Lynch’s work is similar to the zen garden where the meditator is told there are seven rocks, but only six are ever visible. We know the seventh rock exists, but we must learn to accept that we’ll never see it.

“I have no idea where this will lead us, but I have a definite feeling it will be a place both wonderful and strange.”

The Return is a continuation of ideas Lynch has been grappling with for the past two decades, more so than it is a continuation of the Twin Peaks universe. People looking for continuity and meaning between the old series and the new may feel lost — even let down. Lynch’s ideas haven’t been sitting in stasis like Agent Cooper, however.

The Return is the next step in a mode of discovery Lynch has been working out since his early shorts, one that may have met maturity, or as close to surety as Lynch allows himself, with 2006’s Inland Empire. In an interview discussing the film, Lynch said: “There’s a story, but the story can hold abstractions. I believe in story. I believe in characters. But I believe in a story that holds abstractions, and a story that can be told based on ideas that come in an unconventional way.”

The Return, at first, attacked you with its unfamiliarity. This isn’t my Sheriff Truman.

Lynch deals in abstraction ruthlessly, and abstraction by nature is a denial of nostalgia, a denial of ‘straight’ time. That denial makes The Return an otherworldly entity in today’s TV landscape.

When the first three episodes of the new season were released, there was an unspoken sense of ill-ease amongst fans and newbies. This… doesn’t feel like Twin Peaks. The dialogue is sparse, the shots are wide, the digital texture feels decidedly off for a show that most of us remember in a glorified VHS/grandma’s busted tri-colour Panasonic TV haze.

The Return, at first, attacked you with its unfamiliarity. This isn’t my Sheriff Truman.

The nostalgia sneaks up on you like that trash monster in Mulholland Drive. The Return is for the true believers, the truly mad fanclub obsessives: Windham Earle conspiracy theorists who can see a Manson-esque Kyle MacLachlan puke creamed corn into his hands and say “Garbenzola, of course!”. Lynch refuses to be easy, but what sometimes gets mistaken for wilful obtuseness is more akin to explorative introspection — which makes the growing sense of familiarity all the more powerful.

Lynch delivers nostalgic resonance not by highlighting what has changed, but observing what hasn’t. There’s an immense yet subtle chord being struck when Shelly Johnson, observing James Hurley at the Bang Bang Bar, says “James was always cool”. Fans uniformly dismiss James as the show’s cringiest goof (pre-Michael ‘Brando’ Cera), the guy who sings “that song” etc. Yet by the time James himself is on the stage of the Bang Bang singing said song, it’s not a moment of sentimentality nor craving, but one of thundering stillness — one telling us that time is as hot and expansive as Norma’s pies; that for all our questing through the universe, Dakota, and Dougie, the town and people of Twin Peaks are unstuck, and are dragging us into their beatific malaise.

James, as we perceive him as cultural artefact, was formed by the generation that fell in love with Twin Peaks in the age of message boards and MSN. We created a dislocated but well-kept interpretation that unknowingly removed itself from the old intentional corniness tied to that 20th century idea of television and identity. With that moment in The Return, years of smart alec James shitposting left me, this wasn’t my Twin Peaks, but theirs: Shelly Johnson’s, where James was and is cool.

The Return teaches us that familiarity is a personal construct.

“You’ve got a problem of a different sort here, Coop. Two and two do not always equal four.”

Twin Peaks has always explored the frustration that comes with not being given the answer, with the ultimate response being that doubt is a moral good. Lynch aligns us with that idea using characters: those open to uncertainty (Coop, Briggs, Cole, Hawk) are the show’s moral compass — the ones who understand mystery is a matter of acceptance.

The frustrated characters become avatars for the viewer: the teen sleuths driving themselves mad in their search for answers, Sheriff Truman longing for justice, Deputy Andy copping a rock in the noggin mid confused obsequiousness. They’re all flailing in their attempts to follow the winding Dao-lite labyrinth laid before them by a chaotic yet literal parallel universe.

The Return is Lynch taking us on the journey which characters like Donna and Audrey made 25 years ago, the long road to discovery by way of patience. In the new season, as in the old, it’s Agent Albert Rosenfield who articulates the frustration of not knowing, or having the path to knowing in the hands of wishy-washy spiritual journeymen like Cooper and Cole — “fuck Gene Kelly, you motherfucker,” he says, to no one in particular. He remains the show’s knowing wink, literally rolling his eyes at Lynch on behalf of all of us.

Yes, on one level Dougie is the literal answer re: saving Agent Cooper and stopping BOB. But the Dougie side-plot is hilariously drawn out to bring a tease worthy of Audrey Horne herself. Lynch knows we all want Coop back. He’s coming, of course. Maybe. But first share a coffee with Dougie (and by proxy, Coop): brain-dead, startled, curious, desperate to piss. He’s a stand-in for the modern viewer, snapped from one universe to the next, drowning in a torrent of information, lost and bobbing in a stream while glued in place, feeling the familiar as unfamiliar, unable to grasp it — a man out of time, between space, walking into glass doors.

In its collapse of what we expect of TV, movement, and cathartic progress, The Return allows us to reconsider ourselves as consumer and individual. Three minutes of a man sweeping up at the Bang Bang is as key to unlocking this journey as Dougie finally hitting the right pie/coffee/suit combo and reawakening Coop.

“We are like the dreamer who dreams and then lives inside the dream.”

The glacial pacing and collage of profundities is an invitation to dislocate ourselves from the rapidity of modern media consumption, and the austere certitudes of prestige television. The Return says: viewer, walk with me, but know, I am not your foot.

Step out of the lodge and remind yourself that the known can always be unknown. That the log saw something that night. That that gum you like is going to come back in style. That the owls are not what they seem.

Patrick Marlborough is a writer and comedian based out of Fremantle. He tweets at @Cormac_McCafe.

—

You can find every episode of the Twin Peaks revival on Stan Australia. Catch up soon! The finale airs on September 4.