Junk Explained: Everything You Need To Know About The Sony Hack

What got leaked, who did it, and what it means for global security.

If you happened to be trawling through the internet late last week you might have been a little nonplussed if you came across a sentiment like this:

Kim Jong Un is now officially the most powerful man in Hollywood. Please note the time and date in your logs.

— Seth Grahame-Smith (@sethgs) December 17, 2014

As news travelled that Sony Pictures had altogether abandoned its upcoming release of the film The Interview—on account of threats made by a shadowy group of hackers who may or may not have been backed by the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (aka North Korea)—reactions varied from confusion, to outrage, to fear. Directed by Seth Rogen and Evan Goldberg, and starring Rogen and James Franco, The Interview is a comedy caper about a trashy TV host and his producer who, after scoring an interview with the DPRK’s leader Kim Jong-un, are charged by the CIA with assassinating him.

The North Korean government had previously issued harshly worded statements warning against the film’s release (there were more threats made overnight), but nobody really expected anything to come of it.

But then Sony Pictures Entertainment—the studio behind The Interview—was hacked, its data stolen and disseminated online, and, finally, threats were made against any theatres planning to screen the film, and the release was summarily cancelled. So what the hell went down?

How The Hack Happened

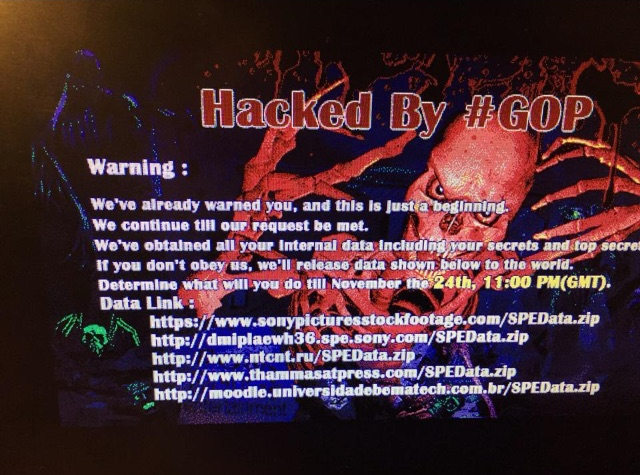

On November 24, the Sony Pictures Entertainment computer network was breached. Employees found that their computers displayed the following image:

The hackers—calling themselves the Guardians of Peace, or GOP (not that one)—had obtained hundreds of gigabytes of Sony’s data, wiping much of it in the process in an attack that an investigating security expert referred to as “unprecedented”.

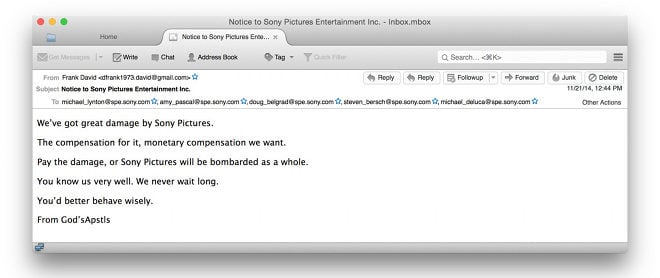

The cryptic-seeming message that “we’ve already warned you” was apparently a reference to an earlier email addressed to Sony executives, claiming, in broken English, that hackers had obtained “great damage by Sony Pictures”, and demanded “monetary compensation” in return (it was signed, confusingly, not by GOP, but by ‘God’s Apostles’).  This earlier email had apparently gone mostly unheeded. We know this because pretty soon the GOP started leaking Sony’s data online, including the emails of its Chairman Amy Pascal, who had seemingly not even read the initial threat.

This earlier email had apparently gone mostly unheeded. We know this because pretty soon the GOP started leaking Sony’s data online, including the emails of its Chairman Amy Pascal, who had seemingly not even read the initial threat.

What Got Leaked?

The leaks began as something like a public inconvenience for the company. Early press coverage revolved around a truculent series of emails between Sony Pictures Chairman Amy Pascal and independent producer Scott Rudin, in which they bickered over the progress of an Aaron Sorkin-scripted Steve Jobs biopic, referred to Angelina Jolie as a “minimally talented spoiled brat”, and made racist speculations about what sort of movies President Obama likes best (they guessed 12 Years a Slave, and Ride Along; because blackness, haha).

This was all pretty scandalous, but mildly so. Pascal and Rudin have since publically apologised, although there’s sure to be more drama mined from their correspondence. Other leaked documents revealed Sony employees’ private information (including Social Security numbers), and their dissatisfaction with the amount of Adam Sandler movies they were forced to work on.

Also exposed: the pay disparity between Jennifer Lawrence and Amy Adams and their male costars on American Hustle. In addition to the leaked documents, the hackers also released entire copies of upcoming Sony films, including Brad Pitt’s Fury, the new Annie remake, and Mike Leigh’s Mr. Turner – which soon found their way onto file-sharing sites. Also leaked: a script for the newest James Bond film.

How Did The Interview Get Pulled By Sony?

These leaks were pretty interesting and made for good press coverage, in a rubbernecking sort of way, but they seemed basically harmless: just another cyber-scandal, in our new, leaky society. But lurking behind it was the ongoing mystery of the hacker’s motives. They seemed to be after money, but the general suspicion that they would be linked to North Korea kept percolating.

The hackers themselves denied having much of an interest in Rogen’s film. In a statement to the Salted Hash blog they said “our aim is not at the film The Interview”, but also claimed, rather contrarily, that the film is “very dangerous enough to cause a massive hack attack”, and harmful to “regional peace and security”. The DPRK government itself denied any involvement, although a spokesperson speculated that the North has “a great number of supporters and sympathisers” worldwide, including “champions of peace” who could perform a “righteous deed” against US imperialism.

At any rate, The Interview wasn’t mentioned among the hackers’ demands until December 16, when another message appeared, warning of the “bitter fate those who seek fun in terror should be doomed to”: “[s]oon all the world will see what an awful movie Sony Pictures Entertainment has made”, the message read, “[t]he world will be full of fear. Remember the 11th of September 2001.”

Although the veracity of the threat seemed questionable—“there is no credible intelligence to indicate an active plot against movie theaters within the United States”, a law enforcement source told the New York Post—Sony cancelled the film’s New York premiere, and quickly advised theatre distributors that they could choose not to show the film at their discretion. Soon four of the five major North American theatres chains—Regal Cinemas, Cinemark, Cineplex, and AMC Entertainment—announced their intention to drop or delay the film, with other, smaller organisations following suit.

And then Sony—perhaps taking advantage of the excuse provide by the theatres’ decision—up and pulled the plug altogether. The studio announced the cancellation of The Interview’s theatrical release (Christmas Day in the US, next year in Australia), adding later that they had “no further plans” for a home video or VOD release. Sony has also done their best to remove all promotional material for the film, with the Facebook page, Twitter account, and official copies of the trailer now deleted.

Who Got Upset?

Phew. Heaps of people. Celebrities and Hollywood figures tweeted their dissatisfaction, including Judd Apatow, standing up for his protégé Rogen; Steve Carrell, who had a North Korea-set comedy in development that was summarily cancelled when the shit hit the fan; Ben Stiller; and Rob Lowe, who cameos in the film. Special mention, basically, to rich old white men, who so rarely (or too often?) get the opportunity to be outraged about stuff and really took this one to heart.

George Clooney excoriated the press for abdicating its duty in its pursuit of the hacking story, as well as the Hollywood bigwigs who refused to sign a petition he circulated in support of Sony. Aaron Sorkin—himself the subject of some unflattering information from the leak—pronounced that the “wishes of the terrorists” had been fulfilled by the American press, who chased gossip and “schadenfreude-fueled reporting” over the real story. Amy Schumer came through with a well-timed callout to Kim Jong-un’s sometime pal Dennis Rodman:

RODMAN, where ya at?

— Amy Schumer (@amyschumer) December 18, 2014

In rather more significant blowback, President Obama said that Sony had “made a mistake” in their decision to pull the film (the studio has defended its decision).

Not so upset: the hackers, who released a statement congratulating Sony on its actions, and generously offering to “ensure the security of your data unless you make additional trouble”.

Who Actually Was Behind The Hack?

The leaks have been traced back to a hotel in Bangkok, Thailand, called the St Regis. An IP address used by the Sony malware to communicate with the hackers has also been traced to a wireless network at a Thailand university. The hackers either could have been at those locations in person, or worked remotely.

Whatever they did there, it probably looked something like this:

For a time, the evidence pointing to North Korea seemed flimsy and disputable. According to Wired, some malicious files associated with the hack were found to have been compiled on a machine using the Korean language, but the language settings could easily have been changed.

Cyber security experts say that the whole event bears many similarities (right down to certain components in the malware code) to the activities of a group known as DarkSeoul, an allegedly DPRK-affiliated group who staged attacks on banks and media companies in South Korea in 2013 — but code like that can easily be sold, or adapted by other users.

Add in the fact that the DPRK had denied involvement, and that the hackers initially requested only money, and the connection to North Korea seemed weak. But then on December 17 US officials announced that it had found North Korea to be “centrally involved” in the hacks, and, the next day, revealed that the government was weighing up a “proportional response” to the DPRK’s actions.

“Centrally involved” is, however, not exactly the same as “they personally did it”; speculation remains that the hackers themselves may be an independent group sponsored by North Korea, perhaps working in collaboration with one or more Sony employees. At any rate, North Korea is known to have a highly sophisticated cyber warfare cell known as Bureau 121, whose 1,800 cyber-warriors are considered the “elite” of the military.

Meanwhile, the DPRK continues to deny its involvement, and has even offered to take part in a joint investigation into the hacks.

Was Sony Justified In Pulling The Film?

For a day or two there it seemed like The Interview might forever be consigned to some vault. Speculation swirled that Sony would never release the film at all, in order to completely write-off the loss for insurance purposes. But in the wake of Obama’s comments, Sony Entertainment CEO Michael Lynton made some noises to the effect that they are surveying alternative distribution possibilities – which could mean a bunch of things, most of them loss-making for the corporation’s bottom line. On Sunday, Sony lawyer David Boies went on Meet the Press and reiterated Lynton’s message.

Depending on whom you believe, the potential loss of The Interview is either no big deal, or a true blow for free expression. The film had begun screening for critics before it got pulled and responses were mixed. Scott Foundas in Variety referred to it as “cinematic waterboarding”; while David Ehrlich, in Time Out, calls the film “hysterically violent” and refers to Rogen as “the most ambitious mainstream comedian in Hollywood”.

For what it’s worth, Rogen and Goldberg’s previous film This is the End (2013) is an underrated gem, including the finest Michael Cera performance yet put to film:

Critics (including Obama) have faulted Sony for succumbing to censorship, but that’s a designation that doesn’t seem to sit quite right. It’s one thing for a government to censor freedom of expression within its own borders, and another thing for a foreign government to go to lengthy, extortive efforts to prevent a film depicting the irreverent, explosive death of its head of state from being distributed. It’s another thing also when said foreign government is notoriously bellicose and erratic, and when said head of state is thought to have a great deal to prove and much to lose.

Some commentators have started comparing the movie to Charlie Chaplin’s The Great Dictator, a 1940 film well loved for its satiric, cutting riff on Hitler right as the Nazi regime was at its height. But World War 2 had already begun by the time that film was released, and the question of the US’s potential involvement in that conflict was an emergent one. The Kim dynasty has been a notoriously cruel and destructive regime—especially to its own citizens—but if Rogen and Goldberg are using their film to make explicit political commentary on the DPRK’s crimes, they have been suspiciously quiet about it. There’s little sense internationally that there’s any sort of appetite for outright conflict with North Korea. Freedom of expression is a great thing to defend but it sure helps if there’s an intelligible motive behind that expression beyond “it’s funny”.

It’s important to remember that this isn’t just about American expression being curtailed – note again the hackers’ alleged statement that the film is harmful to “regional peace”. Sony Pictures does have close links to its parent company in Japan, where the government is currently undertaking delicate negotiations to free Japanese citizens kidnapped in North Korea. Sony Corp CEO Kazuo Hirai had apparently been personally concerned about the movie’s content for months.

Basically, the whole brouhaha is a complete mess and extremely strange, and getting stranger and messier by the day. But it also has much to say about the nature of power in our current era, and the vulnerabilities of the intersection between sovereign governments, multinational corporations, the press, and the culture industry.

And if you find it unlikely that Seth Rogen and Kim Jong-un would be going head-to-head in one of the first major cyber wars of the new millennium, be not afraid. Welcome to the 21st century. This is real life.

–

James Robert Douglas is a freelance writer and critic in Melbourne. His work has been found in The Big Issue, Meanland, Screen Machine, and the Meanjin blog. He tweets from @jamesrobdouglas