Junk Explained: Can People Working In Detention Centres Actually Go To Jail For Revealing Child Abuse?

And why would the Labor Party vote for that?

Yesterday a piece of legislation called the Border Force Act 2015 came into effect. Passed by both major parties on May 14, the law mandates the formation of a new super-agency, the Australian Border Force, which essentially merges old Immigration and Customs duties like security at air and sea ports, patrolling Australian waters and running detention centres.

Resplendent in a spiffy new black uniform, new Border Force Commissioner and former senior AFP officer Roman Quaedvlieg declared during his swearing-in ceremony that “our Utopia, our country is under constant threat,” which doesn’t sound ominous and a bit scaremongery at all.

The creation of what roughly equals our very own Department of Homeland Security to stop refugees on fishing boats is weird enough. But what’s seized the public imagination about the new law is the prospect that people working in detention centres could be jailed if they speak publicly about what happens inside them. A section of the Act forbids anyone who’s worked in immigration detention from disclosing “protected information” on pain of up to two years in prison, which opponents claim is tantamount to criminalising the reporting of child sexual abuse.

–

How’s That Going Down, Then?

The fallout to that part of the law has been immense; yesterday more than 40 doctors, teachers, childcare and humanitarian workers released an open letter declaring their intention to continue speaking out about conditions in our Nauru and Manus Island centres, and challenging the government to prosecute them for it. The letter’s signatories and numerous medical organisations claim the gag prevents nurses and other medical professionals from fulfilling their duty of care towards patients, including children.

The open letter has been met with an avalanche of praise online, with the #BorderForceAct hashtag trending nationwide and The Project‘s Waleed Aly lambasting the new law in a video that’s already been watched more than 170,000 times. With that praise has come a lot of accompanying flak for the Labor Party, whose support for the Act enabled it to pass; Labor MPs sympathetic to asylum seekers like Tim Watts and Terri Butler have taken to social media to defend themselves, claiming that existing laws mean workers will still be able to blow the whistle on human rights abuses if they need to, and dismissing media reports saying otherwise as inaccurate.

Backing them up is Immigration Minister Peter Dutton, who claims that the gag applies mainly to personal information like detainee’s real names, and that “the airing of general claims about conditions in immigration facilities will not breach the ABF Act”. There’s also AFP officer Quaedvlieg himself, who’s said he “sincerely doubts” medicos who flout the law will be prosecuted.

So who’s right? Can someone actually go to jail for revealing child abuse in Australian detention centres, or is that a bridge too far?

–

Why Is This Even An Issue?

It varies from state to state, but reporting child abuse in almost all Australian institutions is mandatory. Anyone who works with children, suspects they are being abused or neglected and fails to notify child protection authorities, welfare agencies or the police can face fines, dismissal, disciplinary hearings or criminal charges. These rules are likely to be strengthened once the Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse wraps up, and hands down recommendations; the Commission has been looking into the systemic failings of institutions like the Catholic Church and boarding schools that allowed child abusers to go unpunished, or even enabled them to keep offending, with a view to eliminating those failings as much as possible.

But in detention centres, those rules don’t apply. Workers report alleged or suspected cases of child abuse to the Immigration Department, which has a history of ignoring those reports for up to 17 months. Complicating things is the fact that many of the staff responsible for detainees’ welfare are contractors working for private companies like Transfield Services and Wilson Security, whose staff training procedures are unclear and quite possibly inadequate. Back in May, Transfield executives faced a Senate inquiry into sexual abuse on Nauru and were unable to answer basic questions about how staff respond to sexual assault reports, and how are trained to deal with such incidents.

And there doesn’t seem to be much political appetite to put the “culture of cover-ups” around detention centre abuse under the spotlight, either. A couple of days ago, Greens Senator Sarah Hanson-Young moved an amendment to an immigration bill that would ensure mandatory reporting of child abuse in the Nauru detention centre. It gained support from most of the crossbench, but was voted down by both major parties.

Voting list on amendment to require mandatory reporting of child abuse on #Nauru. Note who voted against. Shameful pic.twitter.com/ie1ORDwExa

— Anna (@werna_) June 28, 2015

Because of these roadblocks, most revelations about child abuse in detention centres have come from whistleblowers leaking to the media or to Parliamentary inquiries — allegations of Nauruan guards assaulting children, security failings leading to sexual assaults, hundreds of cases of self-harm and details about the murder of asylum seeker Reza Berati would likely have never come to light had they not been leaked. If people inside detention centres who want to speak out are legally sanctioned for doing so, hearing about those kind of abuses will become rarer than ever.

–

What’s Actually In This New Bill?

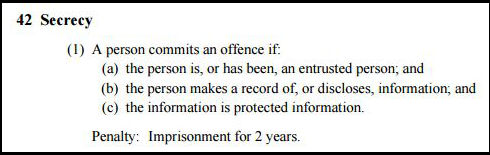

The part of the Border Force Act that has everyone so het up is this bit, Section 42:

An “entrusted person” is anyone who works or has worked in a detention centre, and “protected information” can mean whatever the Immigration Minister or the Border Force Commissioner decides it means. So if one or both of them were annoyed at something politically inconvenient being leaked to the press, Section 42 would be enough to drag a whistleblower to court, provided the person could be found.

To be fair, the bill does provide some exceptions to that rule; an exemption in the bill states that Section 42 does not apply if “the entrusted person reasonably believes that the disclosure is necessary to prevent or lessen a serious threat to the life or health of an individual.” It also gives a pass to any disclosure of information “required or authorised by or under a law of the Commonwealth, a State or a Territory,” or by a court or tribunal. If, for example, the Royal Commission into Child Sexual Abuse, which is considering investigating onshore detention centres, asked a worker to testify, they could spill the beans to the Commission no problem.

Labor MPs are also pointing the Public Interest Disclosure Act, a law passed by the former ALP government which encourages public sector workers to report wrongdoing and protects those who do, as proof that the Border Force Act doesn’t amount to criminalising detention-centre whistleblowing.

But both the Border Force Act and the Public Interest Disclosure Act only protect whistleblowers if they disclose wrongdoing through official channels, and that’s where the trouble really starts. Reporting wrongdoing to a superior — say, in the Department of Immigration — doesn’t mean much if the department ignores it, as they have a history of doing. Moreover, someone leaking to the media won’t find much protection under either of those laws. According to Maurice Blackburn associate in social justice Katie Robertson, it would be up to the defendant to prove their complaint hadn’t been adequately dealt with by authorities — a scenario that’s never been tested before; Robertson says she “wouldn’t encourage” whistleblowers to act as if those two laws would protect them from being found guilty.

In any case, hypotheticals about how a case like this would turn out in court are kind of beside the point; the prospect of being hauled in front of a magistrate and publicly labelled a criminal by the government would be enough to scare plenty of people from whistleblowing at all. Robertson says the Border Force Act expresses a “clear intent to limit information” coming out of detention centres, and given the government’s form in that kind of intimidation it’s hard to disagree; Save The Children workers on Nauru have been deported and referred to police by the Immigration Department for providing evidence of child sexual abuse, and police have investigated journalists reporting on this stuff to try and discover their anonymous sources.

From a political standpoint, it looks like the Border Force Act is going to make that kind of silencing even easier than it is already.

–

So Why Did The Labor Party Vote For It?

GOOD QUESTION, FRIEND.

In recent weeks the Labor Party has very, very tentatively started to make noises about how we might maybe want to possibility consider thinking about not being horrible to asylum seekers all the time. Labor MPs like Anna Burke and Melissa Parke have been pretty vocal about it lately, and last week Opposition Leader Bill Shorten said some very encouraging things in a speech to Parliament:

“Too often refugees are demonised. Still too often the two-decade old toxic, malignant poison of Hansonism seeps to the surface of Australian politics. That genie needs to be put back in the bottle forever…no more dehumanising, inflammatory language. No more false bravado or faux-toughness. Let us no more use some of the world’s most vulnerable people as a prop for politics.”

Problem was, he gave that speech right before the Labor Party voted to help the government close a loophole that could have rendered Australia’s whole offshore detention system illegal; a system which that now-famous open letter calls “a form of systematic child abuse” in itself. Labor maintains its support for the government’s asylum policies is to prevent deaths at sea, but exposing child abuse and horrendous conditions inside detention centres is a separate issue entirely.

It’s also difficult to take the Labor Party at its word considering it’s dropped the principle of non-refoulement, which protects refugees from being sent back to the country they fled, from its draft national platform. Lecturing the government on their harshness towards refugees isn’t very effective if you adopt the policies that make refugee’s lives so hard in the first place.

The ALP’s National Conference is next month, and people inside the party will fight it out to determine what Labor policy on issues like asylum seekers looks like for the next three years. Some are pushing for a more humane refugee policy, while others are looking to introduce even more hardline measures like boat turn-backs — a proposal Shorten has indicated he may support. How that plays out remains to be seen, but Labor have plenty of work to do if their current stance results in laws like this.

–

Feature image via James Fosdike; you can Like and Share it on Facebook via Visualante.