Dick Gregory, Jerry Lewis, And The Limits of The Court Jester

“I learned from my dad that when you walk in front of an audience,

they are the kings and queens, and you’re but the jester. And if you don’t think

that way, you’re going to get very, very conceited.” – Jerry Lewis

The comedy world lost two giants last week: Dick Gregroy (84) and Jerry Lewis (91). Dick Gregory was the perfect intersection of radical and standup. A civil-rights activist who combined black humour with the black lived experience, a man who blended punch line and polemic seamlessly. Lewis was a true comic auteur. A vaudeville holdover who brought his rubber-faced antics and surrealist slapstick to world wide audiences. As a filmmaker, he was an obsessive. His comic creations created what would become the filmic language of the big Hollywood comedy blockbuster. They were both, undoubtedly, iconoclasts.

Both stand as vivid representations of comedians as myths because, in their way, they were the figures that forged the comedic archetypes we now see we now see lionised. The truth spitting satirist-cum-ideologue; the manic-obsessive, multi-medium megastar who turned clowning into high-art. Both were at the extreme ends of what an audience want a comedian to be.

And yet, to our generation, they are relics. Gregory is a “comic’s comic,” at least within white contexts. His legacy is often overlooked or misinterpreted. Meanwhile, Lewis is enshrined in the pantheon of comic Gods, yet so rooted in 20th century aesthetics and ideas (see: his misogyny) that he was spoken of in tones usually reserved for the dead, long before his actual death.

It’s a shame, because in many ways these two men shaped the comedy that our generation grew up loving to this day.

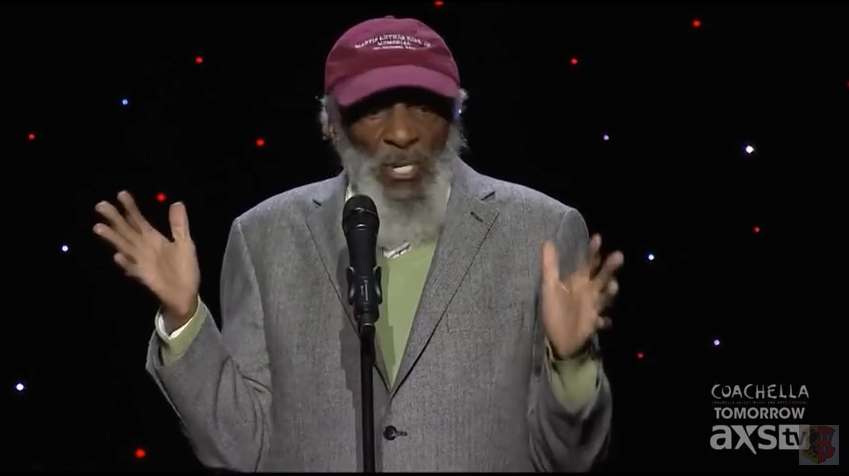

Dick Gregory, The Comic’s Comic

Dick Gregory lived an amazing, revolutionary life. A groundbreaker in comedy and a voice for justice. RIP

— John Legend (@johnlegend) August 20, 2017

Gregory was one of the key figures that brought modernity to standup. He was the first black comic to cross over from the Chitin circuit (the series of clubs where black comedians performed in Jim Crow America) and doggedly maintain his ‘blackness’ while successfully appealing to white audiences. This wasn’t a shtick, this was his life – black culture and language was a vital part of his art, and as such, so was black politics. Gregory not only marched at Selma, he joked about it. “I sat in at a lunch counter for nine months,” a regular bit began, “when they finally integrated, they didn’t have what I wanted.”

“I sat in at a lunch counter for nine months. When they finally integrated, they didn’t have what I wanted.”

As a performer, Gregory was mercurial and effervescent. The progression of vaudeville minstrelsy, Chitin-circuit black spaces, and Gregory’s post-modern self-awareness was like nothing seen before. He beat Lenny Bruce to the punch with acidic political routines that wavered between impersonations, observations, and speculative sketches. And he was black. Gregory created a performative interiority that, until then, had not been afforded to black comics, especially in white spaces. “I never believed in Santa Claus because I knew no white dude would come into my neighbourhood after dark,” he quipped.

“I never believed in Santa Claus because I knew no white dude would come into my neighbourhood after dark.”

He confronted liberal audiences with their hypocrisy in the struggle for black rights. Born and raised in poverty during segregation, Gregory reflected the barbarity of white America with wordplay and jibes. Not many comics of his time were making jokes like, “segregation is not all bad. Have you ever heard of a collision where the people in the back of the bus got hurt?”.

He named his (must read) comic memoir ‘nigger,’ [note: purposefully lower case] telling his concerned mother that “whenever you hear that word, you’ll know they’re advertising my book.” He confronted white audiences with the harshness of the slur: “I said, let’s pull it out of the closet, let’s lay it out there, let’s deal with it, let’s dissect it,” he told NPR in 2000, “it should never be called ‘the N-word.’”

RIP Dick Gregory, A 5 Star General in The War for Human Rights!! Glad to have been in your sphere.

— Samuel L. Jackson (@SamuelLJackson) August 20, 2017

Gregory walked the walk. In 1963 in a Birmingham jail he received “the first real beating” of his life, noting: “it was just body pain, though. The Negro has a callus growing on his soul, and it’s getting harder and harder to hurt him there.” He infamously invited 500 protesters back to his home during the Chicago riots of 1968 to protect them from police violence. He ran for Mayor of Chicago against John Daly in 1967, and the next year he ran for President. Hoover encouraged the mob to whack him. Australian Prime Minister John Gorton refused him entry in 1970, citing him as a radical.

He fasted, he took up conspiracy theories, he spent his whole life fighting something or someone, though ultimately insisted the jokes came first: “humour can no more find the solution to the race problems than it can cure cancer,” he said in an early interview.

If his legacy lays anywhere it’s in representation, in being the first black comedian to truly ‘cross over’ and bring the intimacy and codes of black humour to white audiences. Contemporaries like Red Foxx and Moms Mabley never really made that leap, through no fault of their own. Gregory insisted that Tonight Show host Jack Parr interview him, at a time when black comics were told to do their five minutes, then leave. He changed the narrative, and gave breathing room for performers like Bill Cosby and Richard Pryor to thrive in. Black standup — from Eddie Murphy and Martin Lawrence to Chris Rock and Dave Chappelle — found its way to the ‘mainstream’ (see: white audiences) by way of Gregory’s influence and effort. “I’ve got to go up there as an individual first, a Negro second,” he insisted, “I’ve got to be a coloured funny man, not a funny coloured man.”

Jerry Lewis, The King Of Comedy

Meanwhile, Lewis’s career ran parallel: gargantuan, untouchable, a pop-culture mainstay. At one point, he was the highest paid man in show business. His parents were vaudeville entertainers, he grew up on the white side of the same comic tradition that propelled Gregory. Comedy wasn’t so much a career for Lewis, it was destiny: “funny is my life,” he told GQ.

Lewis blew up quickly. Capturing the electric energy of post WW2 America, still in his late teens, he made a name for himself as the neurotic, wacky weirdo, bouncing off the smooth as silk Dean Martin in an immediately iconic double act – Lewis the shaken to Martin’s stirred, or as Lewis described their artistic cocktail, “sex and slapstick.”

Lewis was the comic that indelibly linked comedy to rock-and-roll and the pop culture zeitgeist: he and Martin’s success was the result of a society that had suddenly elevated youth culture, and taken it from the clubs to the mass market.

After Martin and Lewis’ infamous fall-out, Lewis maintained his stratospheric rise. But he wanted more than madcap slapstick, he wanted to direct. Lewis was a comedic auteur in the tradition of Chaplin. He was a technical wunderkind, he infamously beat every director to the punch with on-set video playback – he knew that production was as vital to farce as a decent pie gag.

But his wit was self-destructively acidic, his obsessiveness often paralyzing. “It is often torture when you have complete personal control,” he wrote, “you answer to yourself once you get it. . . There is no easy way to shake that schmuck you sleep with at night. . . . I have to sleep with that miserable bastard all the time. Very painful, sometimes terrifying.”

He was prone to manic mood swings, he was notorious for flying into white hot rages: “I will do whatever is necessary to make better the stupidity on my part — and therefore go after those who are acting stupid themselves. It’s not popular. You don’t make friends when you do that. And I couldn’t care less.”

“I will do whatever is necessary to make better the stupidity on my part — and therefore go after those who are acting stupid themselves. It’s not popular. You don’t make friends when you do that. And I couldn’t care less.”

Lewis was both genius and clown, and those conflicting roles informed his bitterness, his drive, his doubt, and ultimately his work. In The King Of Comedy Martin Scorsese drew from Lewis one of the most self-reflective performances in the history of film – one of comic as man, mega-celebrity, and failure.

He was a radical, differently than Gregory, but similarly fiery. His comedy was anarchic, his characters were the spoilers of wealthy get togethers and aristocratic self surety. Lewis was the constant fly in the ice-cube of the stuck up and belligerent.

He was the perpetual child and as such fought for childish innocence, once trying to open an (ultimately unsuccessful) chain of cinemas for children. He raised awareness of muscular dystrophy for decades, while struggling with the agony of a childhood limp, busted lungs, and painkiller addiction that stemmed from a particularly nasty pratfall on live TV: “I went for five years and didn’t know where I was. They tell me I did four films, five telethons and a 50-city concert tour. That’s what Percodan is.”

As such, he wasn’t afraid to go dark: his film The Day The Clown Cried is cinema’s most famous missing feature – a film about a Jewish clown in Nazi Germany, who in the film’s final scenes (so the legend goes) entertains children in the gas chamber at Auschwitz. Lewis hid it away from the world in shame. Naïve or not, he was one of the first American directors to dare broach the holocaust as a subject matter. His final film as director, Smorgasbord, was a farce about a man’s many suicide attempts.

For all the tumult and meanness, Lewis created film comedy as we now know it. His films The Bell Boy and The Nutty Professor lay the ground work for the blockbuster studio comedy, particularly those of the 1980s and 1990s. He was the progenitor of Steve Martin, Bill Murray, Jim Carrey, Robin Williams, and yes, Eddie Murphy. He made silliness indiscernible from high art, his on-brand grouchiness remaining present to the end, if ultimately irrelevant.

That fool was no dummy. Jerry Lewis was an undeniable genius an unfathomable blessing, comedy's absolute! I am because he was! ;^D pic.twitter.com/3Zdq9xhXlE

— Jim Carrey (@JimCarrey) August 20, 2017

Two Comedians Who Changed The World

It’s important to remember Dick Gregory and Jerry Lewis in 2017. The two of them did so much to shape contemporary comedy, and the way in which it is consumed. Both men are such immense exemplars of 20th century comedic forms that to truly acknowledge their work is to acknowledge how few great shifts we’ve had since their golden age. It would be reductive to compare Gregory to the similarly polemical cartoonery of Chappelle; likewise Lewis to the high concept struggle for art and meaning via bleak meditativeness of someone like Louis CK.

But I thought of both men last weekend, prior to their deaths, while watching Tina Fey’s ill-toned cake sketch. Gregory once said “hell hath no fury like a liberal scorned.” Shot, beaten, gassed, jailed: Gregory spent most of his energy in the fight against fascism and bigotry. Although Lewis was a misogynist who horribly spouted impotent opinions about women having no place in comedy, Fey made me think of him for another reason. A multi-media comedy business baron whose brand is “no time for your BS” while simultaneously enjoying the BS privilege affords them, Fey’s stunt had a ring of late career Lewis to it. She was, as he often was, a real shmuck.

Through both men we can understand the measure and limits of comedian as provocateur and woke/un-woke canary in the coal mine. In a time when comics are defined by their takes on other takes, the legacies of Lewis and Gregory are vital roadmaps for our critical understanding of comedians, and their ever shifting roles in the cultural discourse. There was a ring of prescience in Lewis’s glib remark: “one day I’ll write the real truth down–the real truth. Then I’ll go to the penitentiary.”

I just hope the nightclubs in the afterlife aren’t restricted.

—

Patrick Marlborough is a writer and comedian based out of Fremantle. He tweets at @Cormac_McCafe.