It’s A Great Time To Love Stand-Up: On Netflix, John Mulaney And The Decline Of The Sitcom

More has changed over the past couple of decades than you might first think.

In the three years following the end of Seinfeld, Jerry Seinfeld got back into stand-up comedy and tried to pull together an hour’s worth of new material. Early on in Comedian, the 2002 documentary which recorded this tour, he asks if anybody in the crowd is thinking about becoming a stand-up comic.

“Does anybody here want to be a comedian?” he asks, locating a man near the front row who may have nodded. “You sir?” Seinfeld, taking a Seinfeldian pause, puts it to him dryly: “Well, this is what it is. You can’t get bigger than me.” Gesturing to the laughing crowd, he says, “Look at this — still, shit. Always shit. That is lesson number one. It’s always shit.”

The point of Seinfeld’s remark, and really of the film itself, is that stand-up comedy is a dirty game in which hitting the big-time ultimately does little for you in the long-term. For counterpoint, the film also contains a parallel story: that of Orny Adams, a younger and more neurotic stand-up who wants to feel the renown of a successful comedian so badly he overlooks his own talent. This is primarily because Seinfeld got what Adams wanted most of all: a sitcom with his name on it. Until recently, the career trajectory of a successful stand-up comedian was expected to culminate in a TV sitcom. The actual work of stand-up was the real stuff — the real art — but it didn’t provide the comedian with the same audience as a long-running sitcom could.

More than a decade later, other forms — including podcasts, on-demand streaming services and digital media platforms like YouTube and Twitter — have disturbed TV’s cultural dominance. Because Jerry Seinfeld was never a great actor, and comedians are not necessarily comfortable working in the TV industry, it’s worth considering the economic and technological changes that have conspired to free stand-up from the sitcom, and what this might mean for the future of comedy.

A True Comeback Kid

There is perhaps no better argument for the decline of the comedian-as-actor than the career of John Mulaney, whose new special The Comeback Kid was produced and released by Netflix a few weeks ago. Mulaney has written for SNL (where he co-created the popular character Stefon with Bill Hader) and he released his first comedy album, The Top Part, in 2009. The Top Part is obviously the work of a young artist, but it’s still an exciting showcase of his talent, featuring some terrific material about eye transplants and Law and Order. The centrepiece of the album, though, is Mulaney’s closer about a “wonderful family restaurant in Chicago”, the Salt and Pepper Diner:

When Mulaney’s first hour-long TV special, New in Town, was released by Comedy Central in 2012 it seemed to confirm his promise, and many started wondering when he would get his own show. The next year he shot a pilot for NBC that was eventually picked up, swapped networks, and then cancelled by Fox. Mulaney, which was cut short by the network after only 13 of its 16 episodes, had (in the comedian’s own words) “a very small but disloyal following”.

Part of the problem with Mulaney — why it felt so offensively disappointing — was because it completely lacked the acuteness and ingenuity of his stand-up; in aesthetic terms, it sat somewhere between a ’90s sitcom like Seinfeld or Friends and their modern-day multi-camera counterparts, perhaps one of Chuck Lorre’s series, a Big Bang Theory or a Two and Half Men. If you are a comedian, this is about the very worst place you can find yourself. Mulaney was derivative, unfunny and — because it was largely based on routines from New in Town — it retroactively tarnished much of his stand-up work.

After its failure, Mulaney retreated back into stand-up like Seinfeld and so many others before him, spending most of this year touring material that would eventually constitute the bulk of the new special. The fact that he sought solace on the road and on tour, calling stand-up “freeing”, only serves to confirm the opposition between stand-up and TV that has operated for so long in comedy. But the success of The Comeback Kid suggests that the market forces of network TV that once determined things in comedy have ceased to exert the total control they once did.

Shot in the imperially beautiful Chicago Theatre, The Comeback Kid radiates the significance of a return to the field because that’s precisely what it is. Chicago is the city where Mulaney grew up, and he conducts himself according to the auspicious logic of a home-ground advantage. The production values are high, and you can see the Netflix money in the small cinematic touches: the rich cinematography and a brief but electric score by Grammy-nominated composer Jon Brion.

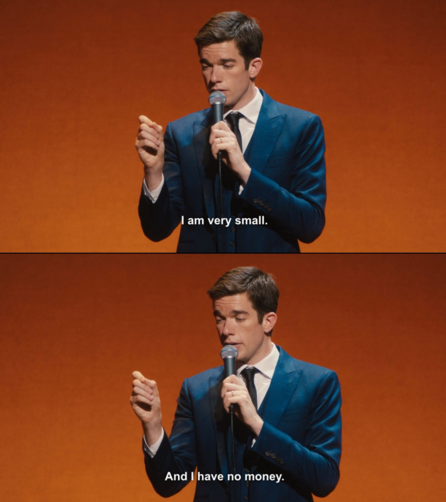

One of the distinguishing qualities of Mulaney’s stand-up is his ability to temper the inherent meanness of observational scrutiny with a winningly self-deprecating boyishness. In New in Town, Mulaney opens with a bit about how, at the age of 28, he doesn’t look any older “just worse”. “Honestly, when I’m walking down the street, no one’s ever like, ‘Hey, look at that man!’ I think they’re just like, ‘Woah! That tall child looks terrible!’” In The Comeback Kid, Mulaney is older (32), married (he jokes about the pleasure of being able to exclaim, “That’s my wife!”) and the creator of a savaged creative endeavour (Mulaney). Despite all this, Mulaney’s endearing sense of his own naivety remains.

Again and again he returns to this childish posture, as much of his best material — the Salt and Pepper Diner, the “fuck da police” bit from New in Town — is drawn from childhood memories, and is aided by his capacity to exaggerate his own youth.

The roominess of the Chicago Theatre’s stage also reveals Mulaney to be an even more assured performer than he was in New in Town. In the opening bit, he instructs the crowd, who offer him a standing ovation, to conserve their energy. “Because we’ve all made a happy birthday sign…” he says, as he mimics that all-too-familiar incapacity to judge the appropriate size for the letters on a birthday card. In his spectacular closer, about a meeting with Bill Clinton just before he became president, Mulaney again strides back and forth across the stage, his long arms and legs nimbly rotating and gesticulating as he describes his mother (Clinton’s one-time almost-lover), using her son as a human shield to plough through secret service agents and “fat Chicago Democrats” in order to meet the presidential candidate.

Mulaney’s comedy succeeds because of his skilful capacity to be at once self-effacing and utterly confident. As in his joke from New in Town that he is as bad a driver as a “hundred-year-old blind dog who’s texting while driving and drinking a smoothie”, a typical Mulaney bit begins with a line like, “When people make fun of me, I deserve it….” Of course, all comedians make use of this paradox to some degree: they put themselves down, but here they are, on the stage, commanding our attention.

What’s The Deal With All These Stand-Up Specials?

Stand-up specials are curious things. They’re at once comedy’s purest form and its emptiest: an anthology of a comedian’s best material, balanced precariously between the amount of rehearsal required to perfect it and the effect of spontaneity required for it to be funny. (One of the perverse things about watching Comedian is seeing Seinfeld repeat the same jokes over and over and over again, and hearing the crowd continue to laugh even as they grow excruciatingly unfunny to us.)

Watching a special, your laughter is guided by the laughter of the audience who heard it live — the people, that is, who had a slightly better time than you. Some comics avoid them completely to avoid “burning the hour”, or using up all their best material. A special is also the best way to experience a stand-up’s work — at least when compared to the experience of seeing that same work translated inconsistently into a bad sitcom.

The audience for these purer forms of stand-up comedy is rapidly growing. This is clear at the grassroots level of websites and podcasts like Australia’s own Sweetest Plum, as well as in corporate initiatives like NBC’s recently announced “cult-comedy app” Seeso. Netflix has invested in this by paying for new specials like Mulaney’s, and has now made an enormous catalogue of them available to a wider audience than they might otherwise have known (including, if I may briefly recommend them, Chelsea Peretti’s One of the Greats, Aziz Ansari’s Live at Madison Square Garden and Bill Burr’s I’m Sorry You Feel That Way).

While promoting his own special Oh My God in 2013, Louis CK spoke about his experience touring Australia. Noting our reputation as the world’s most prodigious illegal-downloaders, he traced our willingness to steal back to a lack of supply. “Everybody in the world is like, ‘Take my fucking credit card and just let me have the thing, and I’ll pay!’” he said. “But if you’re going to be a pain in the ass, fuck you! I can steal all of it!”

Though the release of legal streaming services like Netflix, Presto and Stan in Australia has yet to fully bear out this argument, CK is right to suggest that there is great demand for new forms of comedy. The popularity of Netflix specials, and deliberately experimental comedy as diverse as Rob Delaney’s tweets and weird cinematic TV shows like CK’s own Louie, indicates that we care less and less about whether comedy comes to us in the recognisable format of the sitcom. We ask only that it be as funny as The Comeback Kid.

–

The Comeback Kid is streaming now on Netflix.

–

Joshua Barnes is a writer from Melbourne. His work has appeared in Kill Your Darlings, The Point, Voiceworks and on All the Best Radio and he tweets from @j___barnes.