In Defence Of Student Protests

For tactics that are supposedly counterproductive and immature, these good old-fashioned protests seem to be shaking things up pretty good.

In recent weeks, a number of protests organised by students in opposition to the federal government’s proposed tertiary education reforms have caught the attention of the wider community. The reaction from most politicians, media commentators and news outlets has been overwhelmingly negative, with students accused of everything from naivety to laziness to outright brutality.

No matter who was taking the students to task — current Education Minister Christopher Pyne; former Education Minister Amanda Vanstone; or Annabel Crabb, one of Australia’s most widely-read columnists — the consensus seemed to be that street marches, snap protests and hijacking TV programs are vastly immature and counterproductive methods of protest, and that if students want to be taken seriously they should communicate their concerns in intelligent, respectful ways that clearly outline what they are going through, and what they want.

Let’s ignore, for the moment, the numerous times students have either explained the reasoning behind their actions or protested in original and engaging ways — like the “read-in” protest ANU students are holding outside the Vice-Chancelry; the video uploaded to YouTube by the Q&A protesters outlining why they did what they did; or this excellent piece by student activist Tom Raue in the Herald today.

Let’s also ignore that the entire point of protesting in general is to draw attention to the issue you’re concerned about, and there’s only so much you can do to that end without eventually offending some aesthetic sensibilities, or stepping on some toes.

Egad!

Instead, let’s flip this conversation on its head. Let’s explore the environment the modern Australian student faces, and imagine how any reasonable person would react in similar circumstances.

All We’re Askin’ For Is A Little Respect (Just A Little Bit)

Firstly, this latest spate of paternalistic head-patting is neither new nor original. Students are used to being talked down to. In the vast majority of traditional and online media, we are routinely kicked around as the football of choice by any hack politician or commentator looking for an easy target. We know that, because we are students and because most of us are young, our actions will be filtered through a series of exhausted and infantilising prejudices. The contradictions this can lead to are sometimes as bleakly funny as they are ridiculous. When there’s no march on, we’re dismissed as “slacktivists”, too lazy to get off our phones and hit the streets the way real protesters used to. When there is, we’re told we’re doing it wrong, and should use our social media savvy and gadget wizardry to make things happen online instead.

Protests aside, Friday’s jaw-droppingly patronising rant by Amanda Vanstone ticked every lazy, sneering cliche about students — and all young people — in the book. According to Vanstone, students are part of “the me-me-me generation” with a “misplaced sense of self-importance”, who “expect to get heaps more than other kids their age who don’t go to university”. “I cringe at their naivety,” Vanstone writes. It’s difficult to say what is more cringeworthy: that someone could hold such contempt for people seeking job security and opportunity through tertiary education, or that someone who does was given ultimate authority over the future of Australian students for almost two years.

Perhaps it’s this pervasive attitude of thinly-veiled loathing that explains why policymakers and universities feel they can lie to students with impunity. Christopher Pyne’s plans to deregulate uni fees have been so vociferously opposed at least in part because he is introducing them out of the blue, after repeatedly promising — both before and after the election — that he wouldn’t. Presumably assuming that uni students have the attention span of the average goldfish, he abruptly reneged on his promise before having the gall to pretend to wonder “what all the fuss is about” when people began protesting in response.

Pyne is not the only one who seems to assume that honesty is something that young people have not earned. In early 2013, students and staff organisations at the University of Sydney were striking in opposition to plans announced by University administration to cut 340 staff jobs across campus — including over 100 academic staff — based primarily on their research output rather than the quality of their teaching. At several demonstrations, riot police were let onto campus by the University, resulting in a number of arrests and injuries, with one protester having their leg broken. Later that year it was revealed by student newspaper Honi Soit that contrary to repeated denials, there was evidence that the University administration had colluded with riot police at the protests, to the point of police officers being prepared to take instructions from the University itself.

The Bigger Picture

But the frustration of Australia’s students does not just stem from these specific incidents, and our concern is not just for our immediate circumstances. We’re the generation who will see the really nasty endgame effects of climate change and rising economic inequality, and we know that to have any chance at all of dealing with the fallout, we’re going to need all hands on deck. We’re going to have to rely on the brains and guts of our entire cohort, no matter what postcode they were born in or where they went to school — and if people are staying away from universities because they can’t afford to go, we won’t be able to do that anymore. If we restrict affordable higher education to a shrinking handful of elite private schools, the young woman from Blacktown who could revolutionise solar technology will be working night shifts to pay off her HECS debt until she’s in her forties. The kid from the country who wants to make something of himself in the city will have to be content with his part-time job at The Reject Shop.

We know this, but it seems like the people who are nominally in charge of our futures are either completely unaware, or couldn’t give a stuff. We look around and see those in authority treating our futures and livelihoods as playthings; toys to be broken as part of some idiotic political game, even while the constant refrain is that it is we who need to change our behaviour. Therein lies the cruelest irony. We are told to show respect to people who give us nothing but blatant and needless disrespect. We are expected to trust those who incessantly lie to us. We are seriously supposed to believe that those who expose us to the rigorous attentions of the NSW Public Order and Riot Squad have our best interests at heart. We are directed to play our assigned role in an absurd pantomime, a cruel and vicious joke masquerading as a respectable enterprise, and we are punished when we don’t.

We are told to play by the rules when the game is rigged against us.

Boom Boom, Shake The Room

Given all this, how exactly does one proceed? How do you act in good faith towards someone who has no interest in reciprocating? How do you negotiate with people who would rather roll right over you? How do you talk to those who regard you as not worth listening to?

Easy, really: you don’t. You get angry, and you get a bunch of mates together with some textas and some pieces of cardboard and you let people know, in no uncertain terms, that you are getting screwed. And later that night, when you read about it on the front pages of the biggest news websites in the country — even if they paint you and your mates as a scruffy band of welfare bludgers who ruined decent citizens’ day in the city — they can’t do it without explaining why.

Besides, they were going to call us good-for-nothing spongers for the hell of it anyway; they do it all the time.

Sure, maybe the Q&A protest could’ve been a bit more eloquent. Maybe we could’ve sexed up the National Day of Action with a sea of hands or a flashmob, or something similarly TV-friendly. But if we’d played by the rules the way everyone’s telling us to, would we set the news agenda for weeks on end? Would Clive Palmer be rethinking his support of the education reforms, and would Pyne himself be openly admitting he’d have to compromise to have any chance of fee deregulation getting through the Senate?

For tactics that are supposedly counterproductive and immature, these good old-fashioned protests seem to be shaking things up pretty good. Making a lot of noise and getting up in some grills makes people sit up and take notice, and we’re not the only ones who seem to be realising it.

And if it really is hopeless — if there’s genuinely nothing we can do to stop what’s coming — we might as well go down fighting.

–

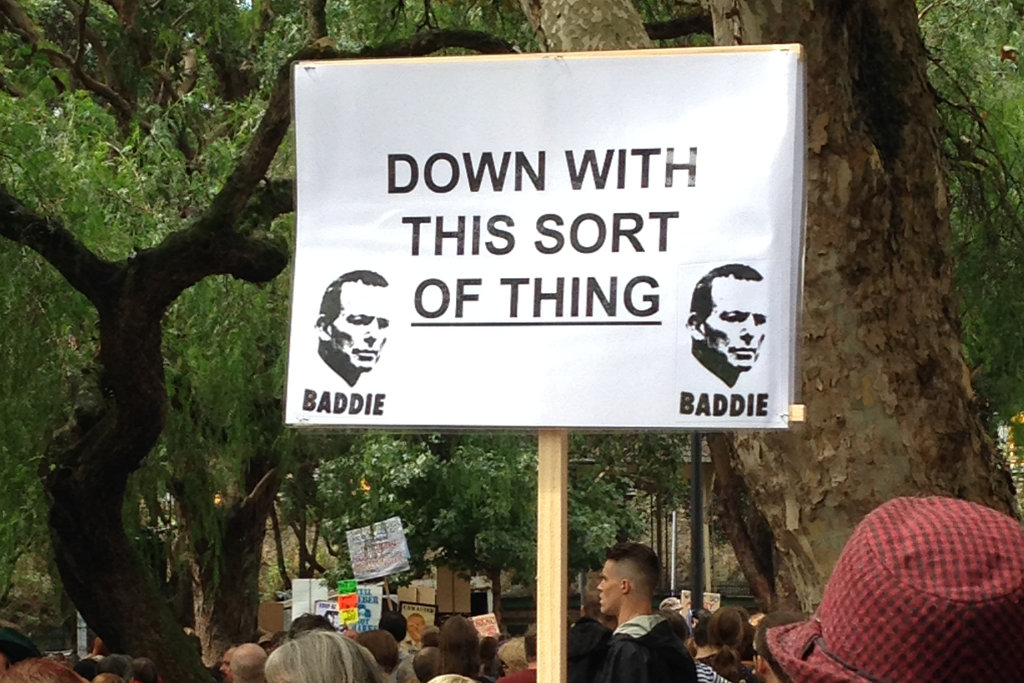

Cover image courtesy of Steph Harmon.

This piece first ran using this photo, from RMIT Catalyst, by Finbar O’Mallon, initially without permission or credit. Our apologies to Finbar and RMIT.

–

Alex McKinnon is a Sydney-based writer and journalist, and former editor of The Star Observer.