The Importance Of Pop Culture As Comfort (Or Why I’ve Watched ‘Rocky’ Many Times This Year)

It can feel like guiltily like escapism, but the renewal it brings can be crucial.

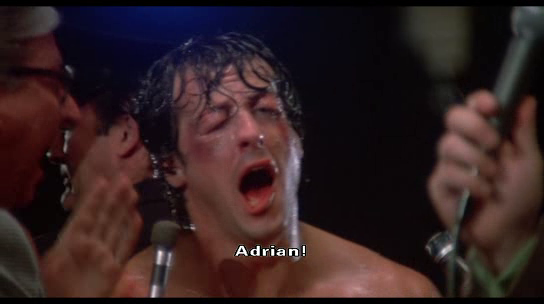

When Donald Trump won the American presidential election, a friend of mine spent the next few days immersed in The Ring Cycle — 14 hours of Wagner. I found the idea masochistic, but I understood the impulse. All that week, after dropping my child off at daycare, I took to my bed with Rocky.

It was a nice break from my Facebook feed, which was lit up with signs of impending disaster, each op-ed seemingly more catastrophic than the next. In between these were articles thrown out like life buoys about the importance of making art; about the value of holding strong to the work we do, work that seems suddenly frivolous in the face of every political crisis and natural disaster.

I didn’t read any odes to communing with art in times of psychic stress, but through my life, this is always what I’ve done. The link between the arts and self-care are strong; a reading list is now prescribed to teenagers in the UK suffering mental health issues, and looking at visual art lights up the brain, even in the tired and depressed. Turning your face away from the news cycle and toward the arts, even for an hour or two, can feel guiltily like escapism, but the renewal it brings can be crucial; a kind of nourishment you may not even know that you need.

And so, for me, it is Rocky.

God, I love this film, and I love every sequel thereafter. Rocky, in and of itself, is a perfect panacea for depression; its narrative arc is pure and clear, its vistas sweeping, its resolution cathartic. Standing alone, untouched by the criticism that dogs the later films, it is beautiful. But seeing the series through gives something richer and more complex, even when (as in Rocky V) nobody’s mind is really on the job.

Rocky As A Story Of Triumph And Vulnerability

Watching all seven films is an immersion; a 40-year ode to a sad would-be boxer with Botticelli eyes, whose only aim in life, when he makes his debut, is to catch the attention of a sad, shy girl.

The vulnerability and ache of Rocky’s emotional landscape is what makes it so easy to slip into when I am feeling vulnerable myself. Coming to this movie as an adult, and watching the series compulsively after seeing the last instalment, Creed, I was completely unprepared for how small the stakes of Rocky’s victory were, and how dark his self-regard.

I had thought, internalising the film’s mythos while I was growing up, and perhaps primed by the sameness of its imitators, that I was coming to a celebration of victory. Instead I found myself torn to shreds — but good shreds, the kind of art that helps reassemble you in a subtly altered way.

No matter how many times I watch this film, I fall almost immediately under its sway; the long slow burn of Rocky’s changing fortunes, his devastating sincerity; the limits of his ambition, his inability to articulate, even to himself, what it is he wants. It is excruciating, and it is tender. The training montages and Sylvester Stallone’s fight choreography are cathartic and wonderful to watch, but they may as well be a makeover montage; the film’s beauty is in its transformation of Rocky from duckling to swan. Its comforts are the comforts of self-esteem, confidence, a place in the world that feels as though it fits.

There are aspects of Rocky, released in 1976, that don’t carry well into the present. There’s one ableist slur that, while deployed by Rocky’s boss Gazzo’s vile driver and intended to illustrate his crassness, completely took me aback. Its politics around women are conservative — second-wave feminism has not touched this film — and it’s hard not to read Rocky and Adrian’s first love scene as deeply coercive. A reviewer at the time of its release described the scene in which Rocky lectures street-tough Marie about her language as ‘supremely touching’, but I found myself completely in sympathy with her rejoinder — “screw you, creepo!”

Its racial politics are equally tricky. Where one reviewer sees Apollo Creed as ‘the template of Black excellence’, another finds a narrative structure based upon a particularly 1970s racism. But no matter how things are positioned in Rocky, as a standalone film, when the other films are taken into account, they move forward.

It’s a given amongst critics, or it was until the release of Creed, that to watch the Rocky films is to participate in a series of diminishing artistic rewards. Stallone’s refusal to let Rocky be, to keep tinkering with the story and coming back to inhabit the character who gave him his first big success, has more or less been universally derided. But it gives me profound comfort that even as the films decline in artistic merit, they find a way to let their characters breathe, to move away from their origins in a way that feels necessary and earned.

Paulie’s racism is addressed in Rocky III, and dissipated by his cantankerous friendship with Apollo. Rocky’s naivety about race is addressed head-on in Rocky Balboa where, in addition to taking Little Marie (the girl he used to scold) under his wing, he forms a close friendship with Marie’s half-Jamaican son.

Women begin to feature more prominently, leading to Apollo Creed’s son, Adonis, getting a love interest who has her own career, her own trajectory, and her own problems to worry about in Creed. The films open their lens to the queer and female gaze, with loving shots of Apollo and Rocky cavorting on the beach, training in crop tops, and revelling in their shared physicality; Paulie and Adrian’s relationship is slowly healed.

I love that Stallone, rather than letting the story stand as a flawed but lauded artefact, pushes his story in a less problematic, but critically disparaged direction. I love that his characters mean more to him than the mythology around one very good film. I love that Rocky, and Apollo and Adrian and Paulie and Mick, get to live and age, to develop calcium deposits on their bones and grapple with their past decisions. It gives me hope for fucking it up, for allowing myself to remain essentially myself, but move, slowly and gradually, towards a better way of being.

That paradox — that progress is essentially about staying true to yourself, while allowing yourself the grace to change — is at the core of every one of these films, and each one teases it out in a way that adds richness and depth. The Rocky movies, boxing aside, are about things we carry in our daily lives; shyness, sadness, frustration, hope. They are stories about bonding with your son, losing your house and starting again, supporting somebody you love through chemotherapy. In these films, small and large acts of endurance and grace are never disentwined; as in life, they can’t be.

And as in life, in Rocky nobody gets anywhere alone. In a way, the films are an explicit refutation of exceptionalism. Rocky isn’t exceptional, at least not as a boxer; it’s not until he’s taken under Apollo Creed’s wing that he really develops any skill. It takes Adrian’s love, Mickey’s coaching, and Apollo’s antagonism to get him into the ring at all. The small crew he amasses, his cut man and his training assistant, all age along with him and are right by his side in his new role of coach, when he takes Adonis under his wing. Though it’s Rocky’s story, none of the members of his immediate community are sidelined to make his victory more spectacular. Instead, their support is dignified, reiterated constantly as crucial to Rocky’s success.

I don’t watch Rocky, curled up and exhausted, and dream of running up the steps to the Philadelphia Museum of Art, horns blaring, fists pumping. Whatever fight is looming, it’s unlikely to be me in the ring; when you’re walloped by depression, sometimes housebound, the action can feel very far away.

Instead, I take consolation from the proximity of Rocky’s loved ones to his success. The idea of emotional labour often gets a bad rap, given that its performed by women and femmes disproportionately, but it gives me comfort in times of political or social crisis that there is work that I can do; that there is something I can contribute, even if it is only support. Self-care, after all, is not an endpoint; it is not a goal in and of itself. We take care of ourselves so that we can carry our community forward, nourished, replenished, and no longer running on empty.

By the last film in the series, Creed, Rocky’s long years of training have boiled down to something like a mindfulness mantra. “One step at a time,” he tells Adonis Johnson-Creed; “One step at a time, one punch at a time, one round at a time.” Fortunes can be made, and lost in an instant, Rocky knows; entire political spheres disrupted; but progress happens inch by inch, and not without the sting of pain.

I think about this a lot, when the world feels overwhelmingly dark, and when any contribution I can make seems too small to be counted. Then I get out of bed, do what I can for the people I love, and see about washing my hair.

–

Jessica Friedmann is a writer and editor living in Canberra, ACT, with her husband and small son. Her writing has appeared in The Rumpus, The Lifted Brow, Smith Journal, Dumbo Feather, Voiceworks, Arts Hub, newmatilda, Australian Financial Review, The Age, Luxury, and more.