I’m Australian And I Want To Feel Safe Too: A Message For The Australian Media

"I, like many others, don’t want to feel scared due to the way I look and the way my name sounds."

“I think for the safety of citizens here — I think [closing Australia’s borders to Muslims] it’s important,” Today Extra host Sonia Kruger said on Monday morning. The comments came during an appearance on Today in which the TV personality discussed the topic: “Do more migrants increase the risk of terror attacks?” This came in response to a column by Andrew Bolt. And, though Kruger was immediately challenged on her claim by co-host Lisa Wilkinson, another question remains: why was she speaking on the subject in the first place?

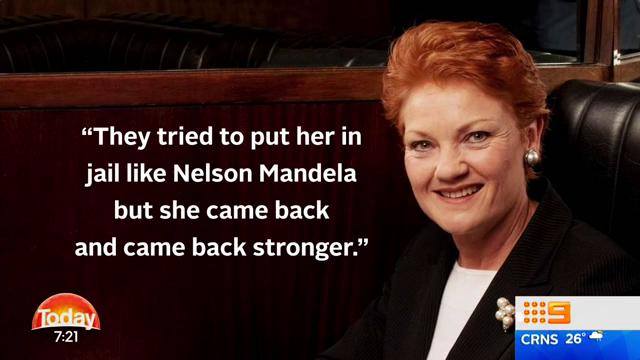

This is the latest in a series of questionable decisions by Australian TV networks in their coverage and discussion of terrorism. After the Paris attacks that killed 130 people last year, Pauline Hanson was paid to appear on Channel 7’s Sunrise as a commentator and used it as a platform to voice her calls for a Royal Commission into Islam. It’s part of a disturbing and persisting trend: apparent non-experts giving ill-informed opinions to a wide audience. And now, more than ever, we know what’s used to stir controversy and attract viewers like this can have harmful effects on Australia’s constituents.

–

Terrorism, Media And Bigotry: I’ve Been Here Before

Appearing on ABC’s Q&A on Monday night, audience member Khaled Elomar explained how he suffered abuse only recently, since Hanson’s views had been given plenty of air in Australian media. “I work in Cronulla. I have worked there for eight years. I absolutely love the place,” he said. “Only recently, after your rhetoric has came on board the media, almost every day I get called a Muslim pig because of you.”

With all due respect @PaulineHansonOz, what is basis of your islamophobic feelings? Hate, Fear or Ignorance? #QandA https://t.co/BjSjuzVf13

— ABC Q&A (@QandA) July 18, 2016

What’s worrying here is that this is somehow the new norm. When a prominent figure (usually a leader) starts making blanket statements against a group of people in the name of “free speech”, it can lead to a rise in attacks against the population in question. You don’t have to go as far back as Nazi Germany for an example — there was a surge in hate crime in the fortnight after the recent Brexit outcome, which was heavily campaigned for on immigration fears.

Right now, things are scary for people like me (and Khaled). They’re scary because we’re worried we may be vilified and attacked purely based on appearance, irrespective of whether we’re religious or not.

I’m a French-Australian, and the attacks in the country of my mother’s origin have affected me. I have family there, my roots are French, its history and culture are embedded in my identity. I’m also Moroccan. In fact, I landed in the North African nation a few days before the Paris attacks as further details rolled in through the news. Foreign media were quick to point out the attackers’ ethnic heritage, as if providing reasoning for why they would attack a European nation: “Belgian nationals of [insert other nationality] origin”. The other nationality was predominantly Moroccan.

Many Moroccan people inside the kingdom weren’t happy with this. “They weren’t Moroccan. They weren’t Muslim. They were crazy,” many said on the streets, in the cafes and between friends. Indeed, reports eventually stated that the attackers drank, smoked and did not attend mosques.

In the aftermath of the attacks, we were flooded with explainer pieces. Why did this happen? Why France? And like Bolt, many were pointing to the country’s North African ‘Muslim’ population. In December, I returned to a country I hardly recognised — and this was most apparent when hanging out in groups of ‘North African-looking’ people. There was a militarised presence in most public spaces and busy transport fares, but it was the suspicious looks and racial profiling that really hit home. This had been brewing for some time. The Charlie Hebdo attacks occurred earlier that year.

Many of the Muslim population in France predominantly identify with its North African heritage, mostly from Algeria and Tunisia. In line with its laicité mandate, France doesn’t collect religious affiliation data, but it’s estimated 5-10 percent of the population is Muslim; the largest proportion in Western Europe, as Bolt pointed out in a column on Monday.

Life is becoming increasingly hard for them. In an attempt to explain possible frustrations the youth face, one man told me: “They [the young Maghrebis] have no hope. Their parents, their grandparents came here to build France [and] they were placed in these ‘quartiers de désespoir’ [suburbs of no hope] where there was nothing. Then, when the jobs disappeared, they were left with less than nothing.”

This is a grim view that not all share. A sentiment that most agree with, however, is their isolation from “the French”. As a young man [from one of the suburbs of ‘no hope’] put it: “They don’t respect us, what more can I do to be French? Even if I was to renounce Islam, which I would never do, I still wouldn’t be French in their eyes.”

–

The Current State In Australia

In Australia we have a completely different set of circumstances. Our history with migration is different, we don’t have a large unemployment rate, and there (arguably) aren’t the same large sprawling suburbs of “no hope”. Our Muslim populations are diverse, largely educated and quite small in comparison — just 2.2 percent. But the results are largely ending up the same. Hate crime is becoming common, far-right racist groups are on the rise and with that rise comes feelings of seclusion and fear. The media play an important role in this; they’re meant to inform the populace so that they can make informed decisions. Instead we see opinion pieces and poorly-contextualised content that often arbitrarily links Islam with terrorism and classifies Muslims as a singular ethnicity before demonises them in kind.

Bolt, whose writing inspired Kruger’s on-air statement, was incorrect in saying that France gets attacked because it lets in the most Muslims. The latest attack in Nice seems to have been claimed by ISIS, even though reports so far indicate that the lone-wolf attacker was not affiliated with the terrorist organisation. The success of ISIS is in creating confusion by claiming countless attacks.

Islamic Studies academic Dr. Shakira Hussein recently said in an article published in Crikey, that we shouldn’t be surprised by Hanson’s resurgence. The political spectrum has been pushed so far to the right that little differentiates One Nation’s policies with Liberal party hard-right factions, she contends. A look at Cory Bernardi’s plans for a right-wing youth organisation is a clear indication of that.

Since 9/11, attacks on Muslims have increased to a point in this country that organisation such as Islamophobia Watch have sprouted to mitigate the resurgence. A survey by University of South Australia’s International Centre for Muslim and Non-Muslim Understanding found that, though most Australians had low levels of Islamophobia, 10 percent were classed as “highly Islamophobic” with “negative and hostile attitudes towards Islam and Muslims”.

In France, as in many other countries, it’s gotten to a point where there is little distinction between who is classed as Middle Eastern looking and who is classed as Muslim, where those who look Arab or North African are more likely to face Islamophobic vilification. Here, you will face Islamophobia if you look visibly Muslim; if your religion is obvious on your person (by the clothes you wear, by the way you shave your beard etc). This is just as bad.

I, like many others, don’t want to feel scared due to the way I look (btw, I can’t change that) and the way my name sounds because of a climate of fear and hate propagated by people like Kruger, Hanson, Bolt and countless other personalities all too common on our TVs. Both they and the people giving them the platform haven’t taken the time to explain the complexities of the multitude of issues involved in acts of terror, and this isn’t going to get any better for anyone until that starts happening.

Sonia, I’m Australian and I want to feel safe too.

–

Scheherazade Bloul is an independent writer and researcher. She is currently undertaking a thesis exploring online female Muslim identity in Australia.