I Marched In March. Now What Happens?

There are benefits to taking like-minded individuals and making a community of them -- but only if it forms the basis of a sustained, cohesive action.

This article was first posted in March 2014.

–

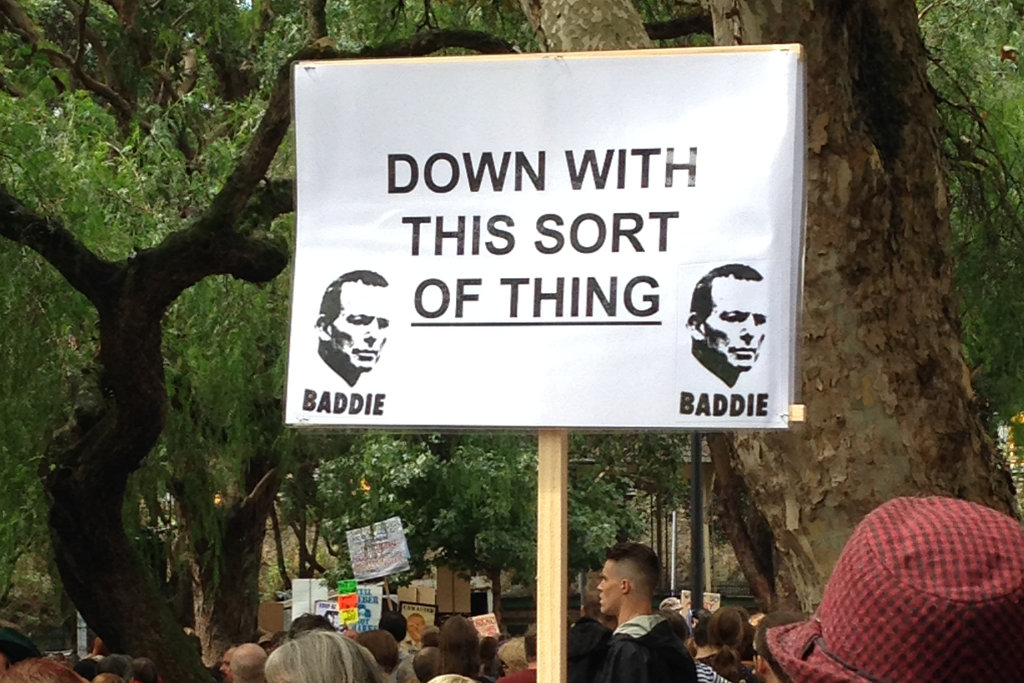

Yesterday I attended the Melbourne edition of the March In March. I wasn’t exactly sure of what I hoped to achieve but, having written a few things on the internet about the less impressive aspects of Tony Abbott’s tenure, I thought I should extend my advocacy into the physical realm. So I went.

The crowd was immense – estimates ranged between 20,000 and 30 million – and it spilled all the from the State Library steps to the Hungry Jack’s on the far side of the Latrobe and Swanston Street intersection. Once the walk started, the column extended down Bourke St from Swanston to the steps of Parliament. It was a spectacle. I joined in the chants and everything, and it felt good. Afterwards though, I couldn’t shake the sense that the feeling-good bit was the only real take-home of the exercise.

We walked down Swanston Street, so it’s possible that some shoppers were moved by our chants, and joined our cause. Television cameras were present, so it’s possible that someone with no prior interest in the issues might have caught a snippet of Van Badham’s excellent speech, and it’s possible that that snippet might have then precipitated an engagement in the debates surrounding offshore detention within this previously unengaged hypothetical person.

More likely, though, this unengaged hypothetical person would have seen the footage, heard the chants, and concluded that it was nothing more than protesters protesting, as is their nature. More likely still, the footage would have blended into the background noise of this hypothetical viewer’s life, alongside the vitriol of shock jocks, the duplicity of politicians, and the sarcasm of fast-food cashiers.

My Problem With The March In March

On March 15–17, the March In March protests took place at over thirty locations around Australia. Its purpose was to express “A statement of no confidence in the Abbott Government from the people of Australia”. The movement proclaims itself as a grassroots, non-partisan movement, which is fine, but I didn’t really expect a stampede of Liberal and National voters to join in. I completely empathise with the expression of no confidence as well, but let’s not forget that the majority of the voting public preferred Tony Abbott as Prime Minister only seven months ago. Furthermore, as Simon Copland has already discussed, the movement finds itself unwittingly adopting the tactics that Abbott himself used in opposition against Julia Gillard. To care about the state of one’s country and the policies enacted in one’s name is admirable, but to protest against the prevailing conditions of reality seems a little quixotic.

So, why protest? To effect change, obviously. Protest is a drastic action, an extreme expression of democratic will, to be resorted to when other avenues – voting, petitioning, lobbying one’s MP – are exhausted or ineffective. It’s also known as “direct action”, but its effects are diffuse. Protesters position themselves as the voice of the people in an attempt to lend weight to the more visible advocates of a cause, or to gain sufficient media attention to establish their cause on the public agenda.

But I don’t see how any of the above measures could play out as a result of March In March: the anti-government position already has some notable advocates – the Opposition, for example, along with those among the fourth estate whose favour hasn’t yet been bought. Besides, how can you expect to influence the legislative decisions of those in power when, ultimately, your issue is that they possess legislative power?

The Moral Vanity Of The Protester

As such, I am not convinced that such an action would amount to anything more than a howl into the void – and yet I can completely understand the howl’s cathartic power. Howling feels good: it releases a sticky, dense rage from deep within. When one is made to feel impotent by a government that governs as if it were still in opposition, whose agenda seems to consist purely of posturing, point-scoring and score-settling, howling can feel like the only option. So what’s the problem then, Ed? Why don’t you just let the people howl?

There is nothing wrong with the expenditure of righteous noise and energy, nor is there anything wrong with attempting to reconcile one’s actions with one’s beliefs: most of the time, such a reconciliation is all we can hope for. It is moral vanity, though, to claim a higher motive, when such a higher motive is an afterthought. Would anyone be honest enough to admit that they’re popping down to a protest for a bit of an endorphin release? Would anyone grab the megaphone and say, “Thanks for coming out, I’m feeling a lot less tension in my shoulders, ta”?

This is my concern with March In March: that a benign but essentially selfish act is being mistaken for a selfless one, and an emotional act is being mistaken for a political one. No doubt there are benefits to taking like-minded individuals and making a community of them, of sharing unmediated perspectives in a highly mediated society, but only if the initial coming-together forms the basis of a sustained, cohesive action.

Protesters Gonna Protest

There is a more pragmatic reason to think carefully about the efficacy of the traditional protest marches, though. In merely playing the role of a protester, one runs the risk of consenting to the lopsided power relationship between protester and protested against: to brutally paraphrase Baudrillard, the easiest way to entrench power is to perform powerlessness. ‘Haters gonna hate’ is an infuriating expression, but it performs a similar function. It allows the acted against to define the actor by their action, delegitimising them and what might have been a perfectly reasonable critique.

When used strategically and harnessed correctly, anger can be a political weapon — but those who employ anger indiscriminately often reduce their dissenting voice to a feeble croak through over-use. Similarly, those that use a non-partisan rally for partisan purposes, or to grind their particular niche-issue axe – such as the ever-present Socialist Alliance, or the anti-international adoption group that kept offering me pamphlets on Sunday – are guilty of garbling the message that is being conveyed.

Where Next For Activism?

Marches are not a dead form of activism, but they are far more effective in specific instances. Pride marches are a great example, because the ends (greater visibility for a minority group) are tied up in the means (said minority group parading through the centre of town). I dearly hope that a protest against Victoria’s brand-new anti-protest laws is organised as well, for the same reason: the ends (the right to protest) and the means (a protest) would be one and the same.

Picket lines work on a similar principle: the existence of a picket line furthers the protester’s objective, which is to hinder access to the institution or site that one is protesting against. Though they have radically differing objectives, the actions of picketers acting against the construction of Melbourne’s East-West tunnel and those trying to hinder operation of the Melbourne Fertility Control clinic have both enjoyed success in their campaigns.

A sense of legitimate grievance is obviously important as well. For instance, a shirtless sit-down protest by Victorian cab drivers won a host of safety reforms after one of their colleagues was fatally stabbed. When a group of pensioners mimicked the shirtless tactics of the cab drivers to protest the lack of an increase in pension payments in the federal budget, it failed to gain quite the same traction.

Unquestionably, though, the most successful direct action of recent times has been that of the artists who boycotted the Biennale of Sydney. Their action was a response to the Biennale’s major sponsor, Transfield Holdings, which holds a stake in Transfield Services, one of the subcontractors currently overseeing the management of the Nauru and Manus Island detention centres. The artists saw this sponsorship arrangement as an exchange of their cultural capital for Transfield Holdings’ capital-capital, legitimising Transfield Services and implicating the artists in the actions of both Transfield organisations. The boycott compelled the board of the Biennale to sever ties with Transfield Holdings and Luca Belgiorno-Nettis, the chairman of the Biennale board and board member of Transfield Holdings.

Many commentators have gleefully pointed out that the artists are shooting themselves in the foot, by discouraging all corporate investment in the arts through their intransigence. I would argue, though, that the shooting-oneself-in-the-foot bit is what makes it such an effective protest. The Biennale artists who have maintained their boycott have sacrificed a wonderful opportunity in the name of reconciling their beliefs with their actions, which makes it much harder to dismiss their act as that of a naïve rabble – though it hasn’t stopped some from trying. The action was highly directed, rather than diffuse, and they used their standing as leverage. Maybe most significantly, the artists’ action wasn’t directed at those formulating policy, but at those who carry out the dictates of those policies. Popular among the likes of Sea Shepherd and anti-logging groups, this might be the site at which less radical forms of activism will play itself out in future.

While such actions place a burden on those at the bottom of the food chain, they are attractive because they force all of us to examine the ways in which we unwittingly undermine our own ethical positions on a day-to-day basis. Chanting is fun, but I’d argue that a sustained self-examination is a lot more useful.

–

Edward Sharp-Paul is a writer from Melbourne. He has been published in FasterLouder, Mess+Noise, Beat and The Brag, and tweets from @e_sharppaul.

Photo by Steph Harmon.