No, Councils Are Not Banning Gendered Toys And Books From Schools And Libraries

The usual suspects are at it again.

If you believe the latest ‘political correctness gone mad’ story that’s doing the rounds, Australia’s children are part of some bold new agenda that erases gender entirely. But the story’s not quite true. Yesterday, The Herald Sun wrote claimed that “Victorian councils are auditing libraries, schools and kindergartens and urging a ban on the terms ‘boy’ and ‘girl’ in a bid to teach kids as young as three to have ‘gender equitable relationships’.”

It didn’t take long for the story to evolve: pretty soon, Victorian councils were going to ban books and toys as well!

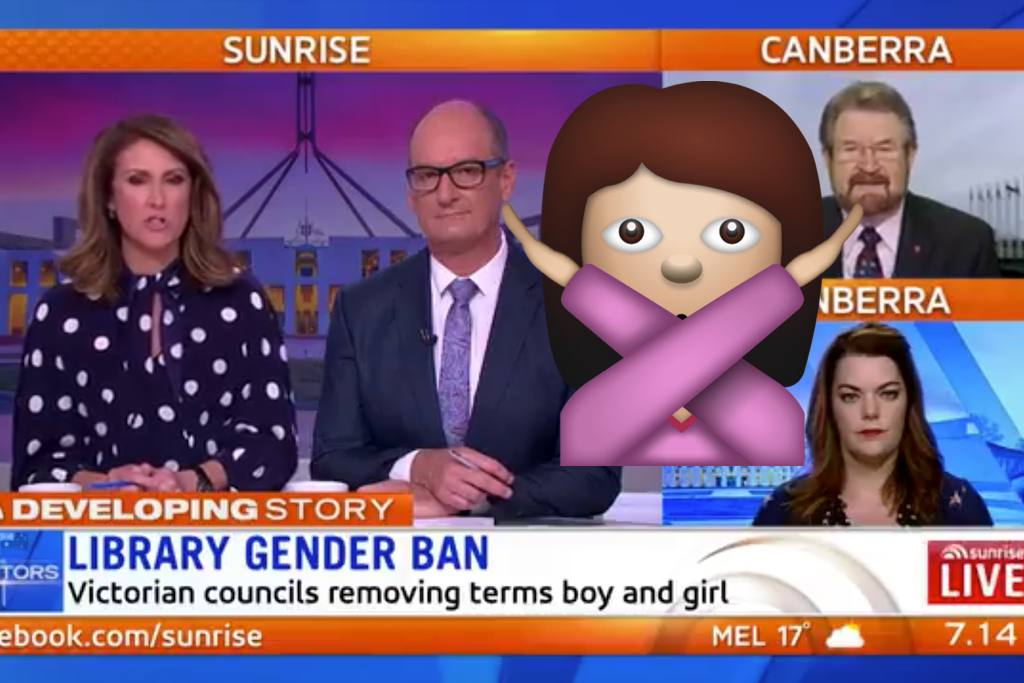

“Councils in Victoria are banning the terms boys and girls as they remove gender stereotyping from libraries and kindergartens,” a Sunrise segment began. “That could see the ditching of Barbie and Thomas the Tank Engine.”

Should libraries and kindergartens be gender neutral..? ?

Senators @HumanHeadline and @Sarahinthesen8 discuss. pic.twitter.com/rNiMYBGDNh

— Sunrise (@sunriseon7) May 20, 2018

Within a day, Sky News, Sunrise, and news.com.au had jumped onto the story, and pretty soon it was trending on Facebook and Twitter.

Problem is, almost every single part of it is wrong.

So, What’s The Truth?

As Mary Lalios, the president of the Municipal Association of Victoria, clarified hours after the Herald Sun story was published:

“There will be no book or toy bans. Kids will continue to read childhood classics like Thomas the Tank Engine at their local library, kinder and childcare centre. We want to expand — not ban — the types of stories accessed by our kids to show experiences beyond gender stereotypes such as girls being the hero who saves the day and boys staying inside on a rainy day to bake,” she said.

The Herald Sun said that two councils, Manningham and Melbourne City, were “among those” urging the ban. But Melbourne City denied the claim.

“Our libraries aim to promote diversity, not censor books,” a council spokesperson said. “None of the books mentioned in media reports have been banned. The books mentioned are in stock at City Library.”

How Did They Get It So Wrong?

In 2016, Melbourne City council asked researchers at the Australian National University to do a literature review on the way that gender bias forms in young kids’ minds. The request was part of an initiative called “Building Resilience Through Respectful And Gender Equitable Relationships Pilot Project”. The plan was to explore how to improve gender equality and reduce domestic violence by intervening at a young age.

The literature review includes a section with recommendations, and that’s where the Herald Sun story was born.

The first recommendation is to “avoid distinction on the basis of gender”, and in one of three sub-points under that recommendation, the authors write “avoid the use of ‘girls’ and ‘boys’ — minimise the extent to which gender is labelled.”

It’s one sentence in a 40-page paper, amongst other recommendations that include minimising television exposure, using story time to introduce themes of gender equity, and avoiding “hyperfeminised toys such as Barbie and Bratz dolls”.

The Herald Sun story dressed up this academic literature review as “new guidelines”, but that’s not true. The research doesn’t appear to have been adopted by any Victorian councils, and many have already explicitly said they would not be taking the most extreme approach when interpreting the research.

One of the paper’s PhD-holding academics has piled on to say how wrong the media reporting originally was.

“Despite reports on the contrary, Victorian councils are not planning to remove any children’s books from library shelves under new gender guidelines informed by our research over the last few years,” Tania King wrote on a University of Melbourne website.

“Research done in 2007 among three to five-year-olds found that at an early age, these kids were able to identify ‘girl toys’ and ‘boy toys’ — and predict whether their parents would approve or disapprove of their choice.”

King reviewed other studies that showed that if children watched more TV, they were “more likely to believe that ‘boys are better'”. And she concluded that existing research should lead to reasonable policy changes.

“We can never remove terms and categories that are a normal part of life such as ‘boys’ and ‘girls’, nor should we,” she wrote. “However, research does suggest that by minimising these distinctions on the basis of gender and making individual attributes and skills a priority, we can help reduce stereotypes, discrimination and bias, and instead, build inclusive behaviours in our children.”