Growing Up Gay In Rural Australia Is Hard, But It Doesn’t Have To Be

Thanks to the allies, you have no idea how important you were.

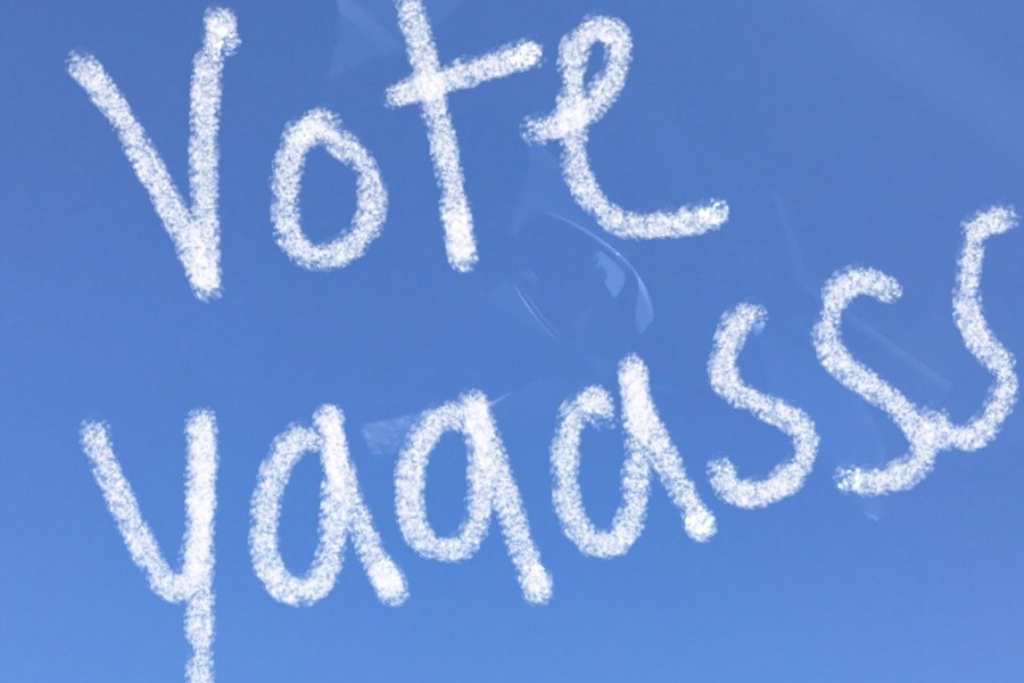

Last week the ABC released an interactive map identifying the level of support for marriage equality in federal electorates across Australia. Deep orange indicated the highest percentage of Yes voters, while deep blue indicated the lowest. As I read the piece, ever the pessimist, I scanned my eyes across the map and rested them upon the bluest spot I could find. It was, at 42 per cent support — the lowest in the nation — the electorate of Maranoa in western Queensland.

I wanted to write this for our beautiful friends and family in the bush, but also wanted something hopeful & positive out there for a moment

— Peter Taggart (@petertaggart) September 18, 2017

Growing Up Gay

I spent 17-and-a-half years in Maranoa. It is where I went to school and where I got my first part-time job delivering newspapers (but mostly getting swerved by cars and swooped by magpies). I traversed the region, visiting its many small towns as a (failed) cross-country athlete and a (successful) teenage public speaker. It’s where I went to the school formal, where I broke my arm on a cricket pitch when I was 10, where I learnt to swim.

It’s also where I first realised I was same-sex attracted and where, at the age of 13, I watched Queer As Folk on SBS in my bedroom, the light from the TV screen obscured beneath a bed sheet for fear of getting caught. It’s where I first heard the word faggot, where I desperately trained myself out of the ‘gay lisp’ and where, for a good five years at least, I prayed every single night that I would wake the next morning and I would be straight and an easier life would be paved before my weary eyes.

“You have no idea what impact even the smallest positive and supportive gesture can have on a young person’s life.”

I can’t truthfully say I was shocked when I recognised that big blue patch on the map. Maranoa is pretty far north of Oxford St, after all. And in my time there, gay people were more often spoken about than they were spoken to. The gay men I was aware of were given cruel nicknames and laughed about. They were not friends, but punchlines. They were poo-pushers and pillow-biters. And when I saw them in the streets or at the shops, I wondered what their lives were like beyond their reputations. I wondered if they were happy, if they were living or surviving.

One thing a lot of gay people around my age heard growing up was this idea that to be gay and unapologetic, you were doomed to live a very lonely existence. You would be ostracised. You would find no real community, no genuine love. As a kid, already feeling isolated by where I lived, I absorbed the idea as fact, as fate. And I believed it for way, way too long, years after I came out.

You Are Never Alone

Of course, the reality is there’s nothing inherently lonely about being gay. Even when it seems hopeless, there are allies to be found everywhere. Yes, even in Maranoa (and a big hello to 42 per cent of you who support same-sex marriage and the 15 per cent who are ‘neutral’). As we barrel through this protracted postal vote campaign, I find myself thinking back to those formative years. I don’t give pause to memories of name-calling or threats, but instead I choose to relive the moments that made me hopeful, the times friends and family, often unknowingly, stepped-up.

“Please know that while at time it may feel like you are completely alone, there are allies everywhere.”

There was my childhood friend, Kellie, the school captain — and though that doesn’t exactly translate as ‘cool’ at every school, she was popular — overwhelmingly so. If we shared nothing else in common, my classmates and I all at least sought Kellie’s approval. In our senior year, as Kellie and I were putting our backpacks away at the beginning of another school day, a nearby group of Year 12s started discussing Brokeback Mountain, which had recently made its way to the local DVD shop. They were telling the usual jokes, mocking disgust at its depiction of anal sex (the sex act that 44 per cent of straight men partake in). As I overheard all this, I had the usual thought — “God I hope they don’t make me part of this conversation”. But as I silently waited for the earth to open up underneath me, Kellie stepped in. As more of an aside than anything else, she said, very matter-of-fact, “well I watched it on the weekend and I thought it was really good”. And the conversation finished. The captain had made her call.

There was Tamara, a teacher in her early twenties. One day in senior art, a student was arguing the case that while gay women in her opinion were “fine” and “relatively normal”, gay men were “disgusting” and “perverted”. I looked down at my sketchbook, flushed, trying to bury myself in its pages. How do these conversations even get started? At this point, the male manual arts teacher — and it’s always the manual arts teacher — had somehow found himself in the room and, entirely unprompted, not only agreed with her but suggested a return to the outlawing of homosexual acts. You know, the ‘good old days’. At the head of the classroom Tamara calmly rested her paintbrush, labelled the argument ‘ridiculous’ and swiftly shut the entire conversation down. The student shrunk into her seat, the manual arts teacher shuffled back toward his hyper-masculine safe space of jigsaws and drills, and to my great relief, everyone moved on to quietly sharing their pastels.

And most importantly there was my mother, Kaye, who stood up to the homophobic rhetoric of my own father. My father was a man who would get up and leave the room if a gay or non-gender-conforming person came on TV, so intolerable did he find their very existence. I considered myself lucky if the storm-out was not accompanied with a swear word or slur. But my mother would combat his behaviour by frequently reminding my sister and I of her gay friends, of the camp art she adored, of the overall worthiness of LGBT people and their positive impact on not just her life, but life in general. She was, and is, my number one supporter and my personal role model when considering how to treat other human beings.

It Really Does Get Better

My heart breaks when I think about every young gay person in rural Australia who does not have a Kellie in the schoolyard, a Tamara in the classroom and a Kaye at home. But if you happen to be reading this and you’re young and gay and closeted and those blinking city lights are too far down the highway to see, please know that while at time it may feel like you are completely alone, there are allies everywhere. They might not be in the next room or even on your street, but they exist and hopefully, at this time more than ever before, they make themselves known to you and the rest of your community.

To the straight allies in the bush, I say this — you have no idea what impact even the smallest positive and supportive gesture can have on a young person’s life. So please use your influence, get out and campaign for marriage equality in your local communities. Remind your neighbours and colleagues about the contribution of LGBT people in your blue patch on the map. Because LGBT people, out or otherwise, are your neighbours, they are your colleagues. They are your nurses and police officers and teachers. And they deserve to know you see them as equal, because over the next two months, they’ll be hearing an awful lot about how they aren’t. Let your voice rise above all the noise — you never know who might listening.

—

Peter Taggart is a writer and podcaster from Brisbane. He is the host of podcast Clip Show and co-host of the Bring A Plate podcast. This post was originally published on Medium.