The Rot Starts At The Top: The Problem With De-Platforming The Far-Right

Facebook is only part of the problem when it comes to stopping far-right extremism.

So, Facebook has finally come to the realisation that white nationalism and separatism is not actually the same as national pride. In a long overdue move, “praise, support, and representation of white nationalism and separatism” will now be banned on the platform.

This comes after growing calls for social media platforms to moderate the content on their sites, including from Scott Morrison, who, following the massacre of 50 people in Christchurch, wants social media companies to “write an algorithm to screen out hate content”.

Politicians in both Australia and New Zealand have come together to put pressure on big social media companies, to “ensure their technology products are not exploited by murderous terrorists”. The Coalition government, in a world-first move, will even be introducing a bill to Parliament this week, where social media executives based in Australia could face up to three years in prison and billions of dollars in fines if they fail to remove “abhorrent violent material” in a timely manner.

While this mounting pressure has evidently forced Facebook to take action, it raises the question about smaller social media platforms, particularly those that serve the furthest fringes of the alt-right, like Gab.

What Is Gab?

Founded in 2016, Gab is a relatively small social media platform “dedicated to preserving… freedom of speech”. The site has a largely far-right user-base, with figures such as Blair Cottrell joining after being ‘de-platformed’ from other widely used sites like Facebook and Twitter.

Gab came under fire after the 2018 Pittsburgh Synagogue shooting after it was revealed that the accused shooter maintained an active account on the platform, and used it to announce his intentions. Until this event, in September 2018, the website’s logo was Gabby the frog, fashioned after the appropriated Pepe the Frog alt-right meme.

Gab has groups like ‘Guns of Gab’ (for firearms enthusiasts), ‘Free Speech’ (self-explanatory), ‘Great awakening’ (dedicated to #QAnon, a far-right conspiracy theory that details a plot by a “deep state” against Trump and his supporters), and ‘Anything Goes’ (where…well…anything goes, so it’s “not recommended for snowflakes”). Moreover, Gab actively welcomes users who have been banned from other platforms.

A recent report authored by the Network Contagion Research Institute (NCRI) and the Anti-Defamation League’s (ADL) Center on Extremism, found that major Twitter bans corresponded with the highest peaks of new memberships on the social media site and directly contributes to increased participation. Analysis of the usage of the word ‘ban’ by Gab users suggests that new users are in fact highly motivated by animosity against Facebook, Google, and Twitter.

Savvas Zannettou is a PhD Candidate from Cyprus University of Technology and a member of the NCRI. He says that sites like Gab, 4chan and 8chan — where the alleged Christchurch shooter posted about the attack moments before it took place — will not take any action to mitigate the spread of hateful content on their platforms.

This is “mainly because they don’t have the resources and because they are not really interested in solving the issue.”

On platforms like Gab, disaffected former users of mainstream social media platforms are able to disseminate their ideologies in various ways without the threat of moderation.

“Memes have evolved into an extremely powerful weapon that can transmit weaponised information…or political ideology with the goal to influence opinions.”

“First, as also seen by Christchurch attack, a popular and seemingly effective way to disseminate ideology is via memes. Memes have evolved into an extremely powerful weapon that can transmit weaponised information…or political ideology with the goal to influence opinions. Users on such platforms also extensively share news articles from alternative news sources that have debatable credibility.”

The dissemination of political ideology specifically is where the problem on Gab and other platforms arises. According to a recent study, Gab is used to disseminate information about world events. The majority of hashtags used on the platform are about Trump, news and politics, with the most popular ones including “AltRight” and “Ban Islam”.

It is through the “constant trolling and sharing [of] hateful comments against specific communities like Jewish people and Muslims they create a constant hateful atmosphere against specific populations,” Zannettou says.

Essentially, users, through the spread of memes and fake news are able to live in a virtual white nationalist world fuelled by male ego and fear of the ‘other’.

When asked about the practice of ‘de-platforming’, Zannettou says that “banning these people is not a solution since they will eventually migrate to other platforms and still be able to disseminate their ideology.

“These people will always find a way to gather and coordinate online even if we ban all ‘alternative’ social networking platforms today. Censoring out 8chan will not help since users will migrate to other communities who can be seemingly neutral and possibly private.”

But if de-platforming is not the right solution, and mounting government pressure is not bound to make an impact on the executives of these fringe communities, then where do we go from here?

The Sickness Starts At The Top

Dr. Clarke Jones is a Senior Researcher at the Australian National University and while he thinks the government is moving in the right direction and believes social media sites have a responsibility to shut down hate speech quickly, he argues that we cannot just focus on social media.

“The narrative starts at the top and gets fed through the media into social media. You’ve got to remember where the fire is lit and how it is spread into other platforms, social media being one of them.

“The narrative starts at the top and gets fed through the media into social media. You’ve got to remember where the fire is lit and how it is spread into other platforms, social media being one of them.

“The rhetoric around refugees and immigration is, as portrayed by the government, that they’re somehow criminals, terrorists, like they have a choice and they’re trying to jump the queue. That’s just not true.”

Part of Facebook’s new shift is to redirect those searching for certain phrases related to white nationalism to Life After Hate, an organisation whose mission it is to help people leave hate groups. The purpose of this is to send individuals who may be prone to developing these ideas to educational resources.

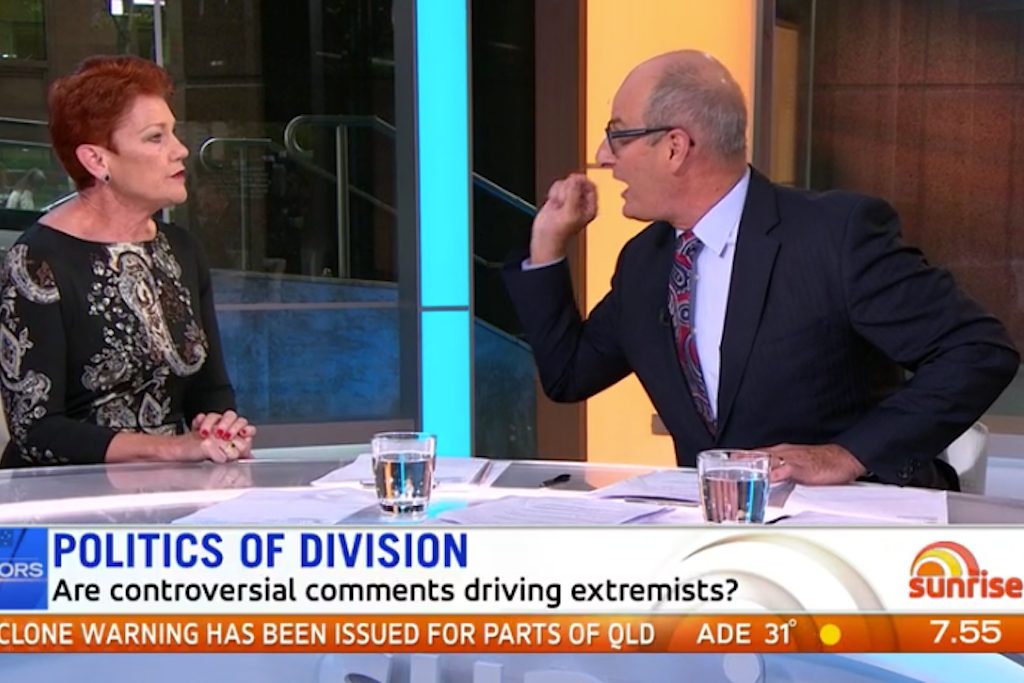

However, as Jones emphasises, the problem does start from the top and must therefore be addressed there. In recent years, we have seen a rise in Islamophobic rhetoric propagated by our politicians. Instances like Fraser Anning’s “final solution speech” and Pauline Hanson’s burqa fiasco may spring to mind as key examples of this. However, rhetoric around refugees and immigration by members of the major parties contribute to islamophobic incidents which may range from abusive words to physical violence.

“The idea that there’s a threat, that we have an immigration problem making it harder to get a job, houses, and cars, has been created. All of these things create a false narrative that there is something being taken away.

If you’ve already got someone who is struggling, who is feeling that they’re losing something, that they’re being marginalised, and they’re vulnerable to messaging they see on these sites, they can become violent.”

His research has found a variety of risk factors that make certain individuals less resilient to imagery and propaganda on these sites. These include low self-esteem, low self-control, less cognitive ability, and lack of protective school environment where, if the resilience is not created by the age of 25 or 26, the individual is vulnerable.

While a combination of these factors can create the basis for individuals to act out in a violent way, what we often see in the media is a search for these factors to justify the violence. Here, Jones emphasises vulnerability “does not necessarily lead to a line of action associated with radicalisation”, so we must be careful.

As for ways forward from the Christchurch attack, Jones says that the government has not shown enough action. “There is a lack of understanding about Islam, and divisive terms are used which feed into the right-wing narrative.

At what point does the government come down on this? Because the back of action reinforces and legitimises these fringe views. It’s almost as if the government says it’s okay.”

Rashna Farrukh is a Canberra-based journalist. You can follow her on Twitter @rashna_f but she probably won’t tweet very much because she prefers to lurk instead.