From Reality Bites To Walter Mitty: Growing Up And Selling Out With Ben Stiller

A journey into Ben Stiller’s directing career, and what it means to be a sell-out.

Lately you might know Ben Stiller as the current king of family funnymen, in his Night at the Museum and Madagascar franchises, but he started his career way back in the early ‘80s, peddling short mockumentaries and film parodies — viral videos before there was really any pathway for them to go viral.

He parlayed that into two cheeky Hollywood-skewering sketch comedy series — first on MTV, then on Fox, both called The Ben Stiller Show — and when those proved short-lived, he used the residual goodwill to kick start his true goal: a directing career.

But somewhere along the way other interests intervened (along came Along Came Polly, and There’s Something About Mary, and those damn Fockers), and he found himself an international movie star, responsible for more than $5 billion worth of ticket sales.

He’s basically your niece’s Robin Williams and your uncle’s The Lonely Island (or sister’s, or whoever it is in your family who’s old enough to remember Janeane Garofalo and Andy Dick) — and on Boxing Day, he’s back with his fifth directorial effort, The Secret Life of Walter Mitty: a naked bid for mainstream respectability and recognition as a director.

Follow along now as we walk through all five Stiller-directed films, and track his progress from a young subversive to a middle-aged sell-out.

–

Reality Bites (1994)

This Generation X touchstone features Winona Ryder — at the height of her elfin adorableness — as an aspiring documentarian drifting through post-collegiate life. It pretty quickly demonstrates a vein of talent that got neglected once Stiller became a movie star. Like, mainly, that he’s a really good director.

The tone of the film is relaxed and intelligent, and he’s got a fluid, articulate visual style that’s far superior to that of pretty much anyone who directed any of his blockbusters.

The film is a clear expression of anti-establishment values. Lelaina and her friends want nothing less than to emulate the lives of their baby-boomer parents. They drift from job to job searching for a way to live authentically outside of the mainstream.

The will-they-won’t-they sexual tension between Lelaina and her pal Troy Dyer (played by Ethan Hawke) is strained by the arrival of Michael — a young executive at an MTV-esque television station called In Your Face, who wants to romance Lelaina and sell her documentary work to his network. But when he allows her artwork to be turned into a reality show farce, Lelaina goes running into the arms of Troy and they live happily ever after in slacker splendor.

–

The Cable Guy (1996)

This black comedy is probably Stiller’s most under-appreciated film. It is most definitely his weirdest. It features Jim Carrey at the apex of his ascension to stardom (in a role for which he copped the then-highest paycheck ever given to an actor, $20 million), playing a deranged cable television installer who wheedles, insinuates and blackmails himself into the life of mild-mannered Matthew Broderick.

The film is a fundamentally unsettling blend of tones and styles. Carrey does his Carrey shtick, but to anarchic, criminal ends, and Stiller shoots the film with the dark, sleek look of a thriller. Here is Carrey beating the snot out of a young, douchy Owen Wilson:

(For comparisons’ sake, here is Carrey a year later, in 1997’s far more family friendly Liar Liar, replaying the same scenario — only this time inflicting the damage upon himself.)

The Cable Guy is a pretty straightforward critique of America’s pop culture excesses. Just as In Your Face twisted Lelaina’s art past recognition, so television twisted Carrey’s character into madness; he even seems to have forgotten his own name, instead giving out variations on the sitcom characters who raised him, like George Jetson and Ricky Ricardo.

–

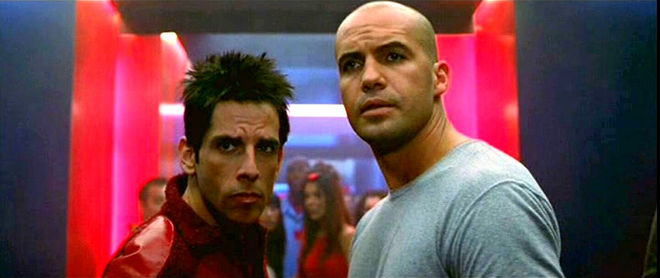

Zoolander (2001) and Tropic Thunder (2008)

In 1998, There’s Something About Mary launched Stiller into comedy stardom. Many starring roles followed, along with those billion-dollar franchises. But his films thereafter show a definite shift in attitude. Having been inducted into a rarified realm of corporate success, Stiller now chose to play along with the establishment.

There are still hints of the subversive voice of his first two films. In Zoolander, a shadowy fashion industry cartel uses political assassination in order to keep its manufacturing costs in developing countries at a profit-spiking low. Tropic Thunder is a spirited joke on Hollywood excess.

As parodies, though, both films are too gentle and inclusive to have any bite. There’s a lot of rib-poking of corporate interests, but the films are ultimately more of an excuse for celebrities and industry figures (now Stiller’s peers) to show up and demonstrate that they can be good sports.

–

But oh well, here’s young Alexander Skarsgard having a water fight with gasoline:

–

The Secret Life of Walter Mitty (2013)

Based on the short story by James Thurber, Stiller’s latest film is the story of a lowly corporate drone with a rich imagination who is forced out of his shell when his job at Life magazine leads him on an international quest for a missing photo negative. Mitty is probably Stiller’s most accomplished work as a visual stylist yet. He pulls off a couple of technically complex action sequences with aplomb, and the landscape photography is stunning; Greenland never looked so good.

The film is also a sincere attempt be the kind of sweet, adult drama now mostly lost in an era of trashy romcoms and flashy blockbusters. If it were set at Christmas, it would have a good chance of becoming a seasonal perennial.

But there’s an unseemly patina of corporatization over the movie. Mitty has maybe the most egregious use of product placement in any recent film. Walter’s journey to self-actualization is bizarrely framed mostly as a journey to having enough life experience to fill out an eHarmony profile. When Mitty calls up an eHarmony customer service rep (played by Patton Oswalt), the film stops cold for a corporate pitch, as Oswalt talks about the dating website’s proprietary algorithm.

Later, the same characters visit an airport Cinnabon, where they enthuse about their cinnamon rolls over lovingly lit shots of the product. It’s weird. Other brands prominently featured, mentioned, or seen: McDonalds, Dell, Papa John’s, KFC, Stretch Armstrong, Heineken, JanSport, Sony, Air Greenland.

In Mitty, Stiller now seems to be suggesting that corporate interests don’t mangle and twist authentic living — as they do in Bites and Cable Guy — but rather that they shape life and give it meaning.

–

So Help Me Out Here. Are You Calling Ben Stiller A Sell-Out?

Well it’s possible to over-state the depth of Stiller’s early anti-establishment tendencies. After all, he cast himself in the role of corporate henchman Michael in Reality Bites. Watching that film today it’s hard to countenance Lelaina’s choice of Troy over Michael, who is sweet and grown-up, although a bit ignorant. Troy is, as Clementine Ford pointed out recently, a major douchebag. We know this because he calls Lelaina ‘honey’ when they argue, he uses the phrase ‘made love’, and because he does a whole bunch of other douchebag-y stuff, like sleeping with women and then ditching them.

But the path from youthful subversion to corporate capitulation still seems clear in Stiller’s films. In some ways, this journey seems like a natural part of growing up. The Cable Guy in particular is the work of a young man headstrong enough to ignore the breach between what an audience expects and what he wants to provide. He was 32 by the time Mary made him a star, and Zoolander and Thunder feel like the product of a maturing guy still horsing around but essentially making his commitment to the establishment known. In Mitty, for better or worse, we find an artist and family man now fully immersed in the corporatisation of his work.

“Selling Out” — that final, irreversible capitulation to business interests at the expense of one’s artistic identity — has always been, like, a fake idea, man. Any artist that wants an audience — any artist that wants to make a living from their work — is going to end up having to make a concession to commercialisation. It’s hard enough to get any project financed at all, subversive or no. As Tad Friend’s June 2012 New Yorker profile of Stiller showed, even with those billions of dollars of ticket sales under his hat, the studios were still reluctant to finance Mitty. This led to haggling over the budget, which probably accounts for the scope of the product integration.

Given the damage wrought by piracy on big-money creative industries, it’s difficult to begrudge artists for cooperating in the monetisation of their product. (Even The Arcade Fire — whose anti-establishment, “live authentically” sentiments could come straight out of the mouth of Troy Dyer — licensed their song ‘Wake Up’ to be used as one of Mitty’s many inspirational music cues.) And it’s hard to hate one guy for towing the line in the face of so much corporate pressure. Whether or not such compromises are to the detriment of the artwork is ultimately for the consumer to decide.

Eventually, making a compact of cooperation with the business interests that control your career is an essential part of having one. Such acquiescence is not always an act of bad faith; it can happen gradually, imperceptibly, as part of making one’s way in the world. It’s easy and cheap to be a subversive when you’re young, as Troy probably knows. But as you get older, compromise become inevitable. Reality bites that way.

–

The Secret Life of Walter Mitty is released nationally on Boxing Day.

–

James Robert Douglas is a freelance writer and critic in Melbourne. His work has been found in The Big Issue, Meanland, Screen Machine, and the Meanjin blog. He tweets from @anthroJRD