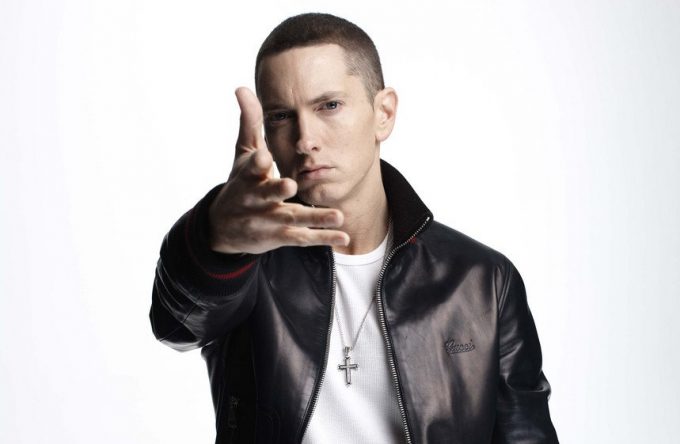

Stop Expecting Eminem To Be Better. He Never Will Be

'Music To Be Murdered By' is another stale facsimile of a style that barely worked in the early 2000s, littered with dud lyrics and cloying, backwards humour.

Late last week, Eminem surprise-dropped what appeared to be his boldest reinvention yet.

Music To Be Murdered By, his eleventh record, draws on the work of Alfred Hitchcock, who Eminem giddily called “Uncle Alfred” on his Twitter account. ‘Darkness’, the album’s lead single, cribs from the music of Paul Simon.

Elsewhere, on the relaxed ‘You Gon’ Learn’, the man makes a crack about Slowpoke and Pokémon. From the outside, it seemed like the most dangerous man in rap had finally embraced his new role: that of a Hawaiian-shirt wearing dad.

That was the initial buzz, anyway. But within a few days, as listeners cracked the relaxed sheen of the record, they discovered the same old man. The aforementioned ‘Darkness’ is told from the perspective of the Las Vegas shooter. ‘Unaccommodating’, the album’s most controversial song, contains a ham-fisted reference to the Manchester bombing that has already been slammed by victims’ families and the mayor of that city. And the thing is littered with the same old anachronistic vocal crutches: songs about using and discarding women; about girlfriends as status objects.

So no, Eminem hasn’t really changed. But why should we expect him to?

This bait-and-switch has been the name of Eminem’s game for at least the last decade. The man’s discography is a constant series of reinventions, each less convincing than the last. Encore is a pale aping of past glories; Relapse a “comeback” record. Recovery tried to be harder. Then Revival tried to be softer. For at least a quarter of his career, the rapper has been trying to find his own sweet spot again, mostly by tearing up what he attempted in the past.

Yet somehow, for some reason, we keep expecting Eminem to do better. We keep buying into the hype. When the critics swooped onto Music To Be Murdered By, they trawled it for comments on our current moment, somehow expecting a man mired in the early thousands to say something to say about the culture or our times. Jon Dolan of Rolling Stone noted that the record has an unusual amount of “intellectual, thematic, and emotional elbow grease.” Alex Petridis of The Guardian called out ‘Darkness’ as evidence that Eminem “is still capable of being a potent force”; a kind of arch, abrasive critic of our times.

In fact, Eminem is none of these things, and his record’s supposed venom lies all in its surface. A half-hearted gesturing towards gun control aside, Music To Be Murdered By is another stale facsimile of a style that only just worked in the early 2000s, littered with dud lyrics and cloying, backwards humour that Eminem hasn’t gotten to work for him for at least 20 years. Maybe the most interesting thing you’d like to say about it is that it’s offensive. But it’s not even really that.

None of that is surprising. But somehow, we are still surprised. So the question remains: why do we expect anything different from Eminem?

Eminem Is Not Your Woke Hero

Eminem is, if nothing else, an exceptionally skilled self-promoter. The man has spent his career building up mythologies, grand stories of his own talent, hardship, and his natural drive for success. These are stories that have soaked into the cultural firmament — that keep us searching his tea leaves for some promise of future portent.

And these are not just outright lies, or deceptions: Eminem was skilled, once. You only get to bend people’s ear for so many decades if you had something to make them sit up and pay attention in the first place, and Mathers did that like no-one had done before. In a recent throwback Pitchfork review, Jeremy D. Larson notes that Eminem’s abrasive, uncouth style electrified the culture. “Whatever he’s become since, there can be no question that Eminem was one of the greatest to ever do it,” Larson writes.

Darkness is why Eminem is still one of the most important writers in all of music. Great great storytelling song on the Las Vegas massacre

— Keith Nelson Jr (@JusAire) January 17, 2020

In fact, it’s impossible to tell Eminem’s story without acknowledging the bite and energy of those early records; his sheer energy as a freestyler. Everybody who knows anything about Eminem, or has seen the surprisingly gritty 8 Mile, knows that he had to prove himself in underground rap battles, and those early scuffles with his peers lent him a near-unrivalled skill for finding a barb.

The stretch comes not when critics try to reckon with the man’s tools, but how he has chosen to use him. Eminem might reflect the culture of his times, but he is no commentator on it. Yet the man himself has carefully fed the expectation that he might be, vocalising his support for gay marriage and dipping his toes into anti-Trump politics.

And, in turn, his most loving critics have taken up the work, arguing that the rapper has the ability to properly contend with the behaviour of his own fanbase in an age where too many disaffected young men are being radicalised.

Eminem used to be cool, now he’s just corny and trying to stay relevant by using leftist politics mixed with edgy lyrics. Rapping about the Manchester bombing was so fucked up.

— *✭˚・゚✧*Queen Rach*✭˚・゚✧* (@rachel_morgan97) January 18, 2020

In a longform article designed to reckon with Eminem’s political impact, writer Alexis Petridis wondered aloud whether the man might have his finger on the cultural pulse. “Did he merely mirror – or, with the ridiculous Slim Shady, even satirise – the rise of the angry white man, or did he help drive it?” Petridis wrote.

The answer is neither. Eminem’s never properly backed a political opinion in his entire life, and his recent output proves that. That’s precisely the problem. These days, we don’t even want him to be good. We just want him to be interesting. And for the last two decades, he hasn’t even been able to manage that.

Eminem Built A Career out of Regression

Eminem’s brief time in the critical sun came in the early thousands. By that stage, hip-hop had finally begun to permeate middle-class culture — the genre explosion in the early to mid-’90s had finally reached the always slow-on-the-uptake critical establishment.

Just like Elvis had done decades before him, Eminem capitalised on an art form that had already been perfected and honed by talented African-American performers. In doing so, he gave a genre that had once seemed scary and underground an approachable Caucasian face.

Everything about the early mythos he built for himself was designed to appeal to alienated but rich American youths. He was dangerous, but not actually. Shocking, but in the way that a fart in a church is.

Even back then, the man styled himself as being without artifice. His career was one built on a kind of cultural conservatism. Years before, Marlon Brando had drawled that he’d rebel against whatever you had. Eminem was that ethos lathered over a blonde crew-cut and packaged in chunks that parents could hate, but still comfortably buy for their kids in a Walmart.

The smartest and most radical Eminem ever got was starting a song with a series of puke sounds. And the joke, always, was on the people who took him seriously.

A Dull Machine of Hate

By around 2005, Eminem had generated a tidal wave of anxious press. He was America’s boogeyman — the dangerous influence leading America’s children astray with his homophobia and his misogyny.

Certainly, Eminem’s frequent use of the word ‘faggot’ was harmful. He helped normalise a slur, turning a word coded with years of life-destroying discrimination into a playground insult, spat by bullies who didn’t even know what they were saying. But, as with everything that Mathers has ever done, there’s not anything substantive enough in his hatred to even properly pick apart.

I don’t believe that Eminem hates gay people. I don’t believe that he hates Donald Trump, either, even though he released an unsatisfying diss track about the President. Hatred requires some kind of interaction with the outside world; some understanding that things happen outside your own head. Eminem has never once acted like he knows he lives on the planet Earth. When he says something cruel, the subtext is always the same: look at me.

He’s been playing that act for decades now. But the Eminem show closed down a number of decades ago, replaced by artists like Kanye West and Tyler, The Creator — controversial figures whose music earns them the right to be discussed with seriousness.

Indeed, in a lot of ways, Tyler should have the last word on Eminem. Back in 2013, Tyler was the subject of one of Eminem’s more repugnant lyrics — “Tyler create nothing, I see why you call yourself a faggot, bitch,” Mathers rapped on ‘Fall.’

That generated some outcry. But Tyler didn’t care. “We were playing Grand Theft Auto when we heard that [line],” Tyler told The Independent. “We rewound it and were like: ‘Oh.’ And then kept playing.”

Eminem’s no boogeyman. He’s no vile, homophobic, hateful demon. He’s just a sad old man who has yet to wake up to his own lack of influence; a suburban dad who spends his time walking hangdog circles inside his own ego.

Joseph Earp is a staff writer at Junkee. He Tweets @Joseph_O_Earp.