The Quiet Horror Of ‘Dunkirk’: Christopher Nolan’s War Epic Will Wreck You

'Dunkirk' is the final act of a horror film... but as a full-length movie.

According to Christopher Nolan, his latest film Dunkirk is “not a war film”. On the face of it, that’s patently untrue. Dunkirk takes place smack bang in the middle of World War II, centring on the English effort to rescue their troops from German-occupied France. It’s a film about war. It’s a war film.

Watching the film, though, it only takes a couple of minutes to understand what Nolan’s getting at. The wordless opening scene follows a small squad of English soldiers through the abandoned streets of Dunkirk. Within seconds, they’re slaughtered by gunfire from unseen combatants. The sole survivor, Tommy (Fionn Whitehead), manages to scramble into the Allied perimeter, and down to the beach for evacuation home.

What does he find at the beach? You know that moment in horror films when the characters realise the gravity of their situation? That they’re trapped — in a remote camp by Crystal Lake, in an alien-infested facility, in a neo-Nazi green room — and surrounded by something malicious that only wants them dead? Moments like these are seared into my brain. They’re terrifying in an existential way, recalling those abject moments of dread when we remember our own mortality.

That’s what Tommy finds on the beaches of Dunkirk. Lines of soldiers – tens, hundreds of thousands of men – sprawled across an empty expanse. Hoping for home. Awaiting ships that will be sunk in the channel by lurking U-Boats. Pressing themselves desperately into queues across a ramshackle pier, awaiting the inevitable attention of the German bombers that swoop out of sombre skies. Awaiting death.

This is Dunkirk. It is, as Nolan describes it, “a survival story and first and foremost a suspense film”. But it’s also the final act of a horror film, possessed of the same heart-pounding tension and the same disregard for the sanctity of human life. It’s not as gory as the typical horror movie, or even the typical war movie — the film notably received a PG-13 rating in the US, which precludes much in term of blood and guts. Regardless, this is a harrowing film: an intense, experiential evocation of war.

Experiencing War

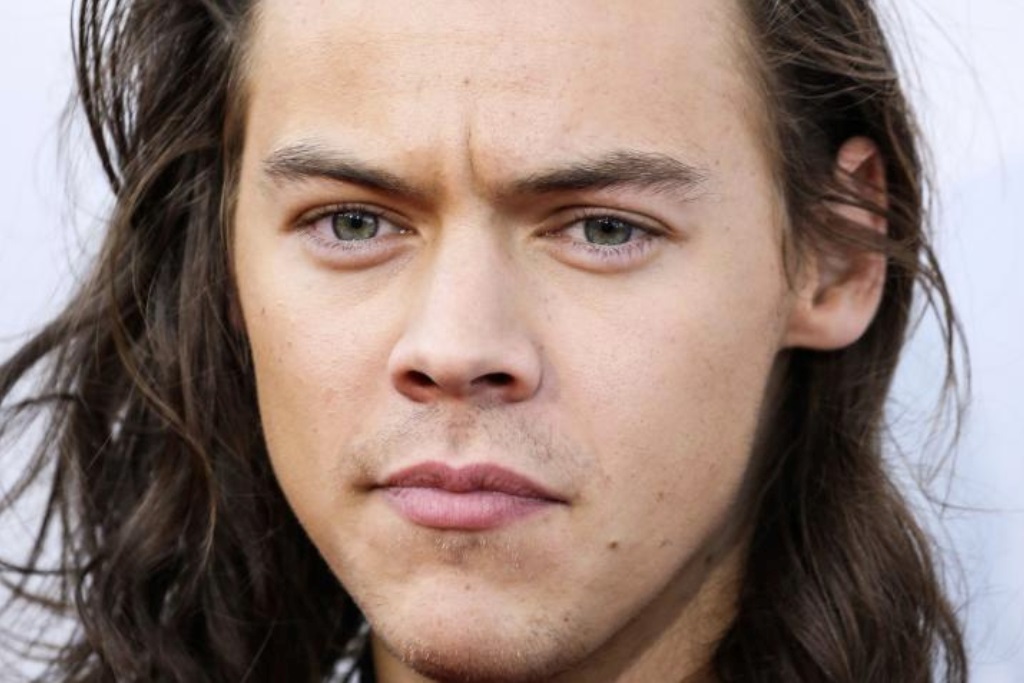

I’m born of a generation with little first-hand experience of war. Nowadays, the average Australian is more likely to have experienced warfare in Call of Duty than firsthand. What Nolan is attempting with Dunkirk isn’t to offer a history lesson to this generation – his film is notably absent any extended consideration of politics or military strategy – but to approximate the emotional reality of war, whether you’re a soldier in the infantry (Harry Styles), a civilian chipping in (Mark Rylance) or a pilot engaging in life-or-death dogfights (Tom Hardy).

In the spirit of great horror films, Dunkirk is a full-body experience. I found myself straining forward as soldiers fought to escape from a sinking ship or ducking with them as gunfire wizzed by overhead. That’s a testament to the film’s formal finesse.

The way Hoyte Van Hoytema’s cinematography captures the vivid beauty amidst the morbidity, the ocean’s opal blue shadowed by the sinking hulls of English destroyers. The way Lee Smith’s editing seamlessly stitches together three distinct storylines, cutting from land to sea to air with breathtaking confidence. The way Hans Zimmer’s score surges and swells and pulls you along with the tide, pulsing and ticking with anxiety-inducing immediacy.

The importance of that craft is evident in the effort Nolan has put into promoting his chosen format for the film: specifically, 70mm IMAX. 70mm film is a now rarely-used high-definition celluloid format (y’know, actual film film) that’s even more rarely-used in IMAX.

If you want to see it in this format in Australia, your only option is Melbourne; Sydney recently began the process of converting to digital IMAX. Critics like David Ehrlich have already asserted that the only way to see Dunkirk is in this gloriously extravagant format, but it’s understandably attracted some mockery for being so prescriptive.

Don't even try to tell me you've seen Dunkirk unless you've physically ingested an entire 70mm IMAX print.

— Sam Adams (@SamuelAAdams) July 18, 2017

you haven't seen DUNKIRK until you've seen it projected onto my enormous ass

— J Rosenfield (@J_Rosenfield) July 19, 2017

Whether or not you care about such format nerdery is probably beside the point; what matter is that Nolan does care about it. And thank God — without him (and the likes of Paul Thomas Anderson and Quentin Tarantino), I doubt Brisbane would’ve gone to the effort of dusting off its 70mm projector for the first time in years. Nolan’s efforts in championing this format are testament to how important the look and texture of Dunkirk is to him.

Silent Storytelling

This emphasis of craft over story feels at odds with the kind of films Nolan’s been making lately. While Nolan’s talents behind the camera are obvious, discussions around the director tends to focus on the intricacy of his narratives — in twisty, convoluted films like Memento, Prestige or Inception — rather than his formal prowess. Dunkirk is, in many ways, a conscious corrective to the overly wordy, exposition-heavy approach Nolan took with films like The Dark Knight Rises and Interstellar.

For long stretches, Dunkirk is entirely without dialogue. The words that are spoken are functional, perfunctory and, often, devastating — as in an early observation that England is hoping to salvage an army of “30,000 men” from the half-million or so soldiers stranded on the beach. The characterisation is similarly sparse; there’s no backstory, no establishing flashbacks, no cuts to worrying wives at home (in fact, there are barely any female characters to speak of). Even the enemy remains ambiguous — the word “Nazi” is never spoken, and the German troops remain unseen throughout.

Rather than rely on the tired tropes of historical films, this is a film grounded in emotional truth.

Horror films tend to humanise their characters; war films tend to valorise them. Dunkirk does neither. I walked out of the film not knowing any characters’ names. That’s by design. As Nolan has said, “You’re not necessarily spending too much time discussing who [the characters] were before or who they will be after.”

Though it ends with a hesitant recitation of Churchill’s famous speech (“we shall fight on the beaches”), Dunkirk refuses to render its characters into symbolic heroes or victims. They’re exceptional by virtue of their ordinariness. Many of these men even act as craven opportunists, looking for any opportunity to get back to England. Rather than depict them as cowards, we’re encouraged to recognise them as normal people, desperate in the face of desolation. That makes it easier to be drawn into the film in the moment, though it does tend to reduce its impact in retrospect.

Without substantial dialogue to tell the story, Nolan leans heavily on Zimmer’s score. It’s an impressive feat of composition: expressive, evocative and undeniable visceral. It’s also, perhaps, a touch overdone: at times the film strains under the bombast of its soundtrack, and its two most memorable moments are found in eerie pockets of silence.

While Dunkirk avoids Nolan’s trademark wordiness, it does retain his common non-linear story structure. The film’s three narrative threads — Whitehead on the beach, Rylance at sea, Hardy in the air — occur across different time frames, taking place over one week, one day and one hour, respectively. At times, crosscutting between these three stories pays dividends, allowing the film to amp up the tension and suggest the tragic scale of the event.

While I found it incredibly effective to say, intercut a downed pilot’s attempts to free himself from his jammed cockpit with a soldier struggling to escape a sinking ship, there are muddled moments towards the end of the film as the three threads interconnect. Still, the film’s most triumphant moment — the simple image of a plane flying across rows of cheering troops — earns its power through the combination and intersection of the three stories.

While Dunkirk might begin in the throes of horror, it concludes with a surge of optimism. The oddly triumphant conclusion comes off as genuine rather than mawkish. Rather than rely on the tired tropes of historical films — photographs of the real-life people, or titles drily explaining the events that occurred thereafter — this is a film grounded in emotional truth.

Dunkirk isn’t striving to immortalise English heroism as a sepia-toned portrait. Dunkirk simply wants to transport you to the battlefield, and experience the horrors that lie there.

–

Dunkirk is in cinemas now.

–

Dave Crewe is a Brisbane-based teacher and freelance film critic who spends way too much of his time watching movies. Read his stuff at ccpopculture or pester him at @dacrewe.