“We Want Rights And Respect, Not Charity Or Pity”: Australian Disability Activists Want To End ‘Steptember’

The campaign encourages people to take up to 10,000 steps a day, to raise money for cerebral palsy. But many people with cerebral palsy can't do that.

If you were raising money to help disabled people, what kind of campaign would you run? One that included those people, and didn’t make them feel lesser or broken, right?

Well, according to disability activists around Australia, the Cerebral Palsy Alliance (CPA) has done the opposite.

The Steptember campaign that CPA has run for the last few years launched this week. It encourages people to take up to 10,000 steps each day in September — and to do healthy lifestyle things, like climbing stairs, standing at work, and running — to raise money to help people living with cerebral palsy. The campaign also raises money for research into the causes of cerebral palsy, and “maybe even one day a cure”.

But ask disability activists, and they will point out a few problems with this. The first is that many people living with cerebral palsy can’t actually do any of the Steptember campaign actions.

The second problem is that, although it’s well-meaning, to raise money to help find a cure for cerebral palsy rests on the assumption that people with cerebral palsy need to be ‘fixed’.

And the third problem is that governments and policies should be the ones who make it easier for people to live with disabilities – not the charity of everyone else. Fundraisers like this work from the assumption that disabled people need a pity party to be thrown for them before they can get the gear they need to move around, get to work, or do any of the things other adults do every day. And that’s hardly fair, is it?

This kind of campaign – in both its goals, and its positioning — has roots in the medical model of disability, an outdated mode of thinking that positions disabled people as broken or wrong, and assumes they need other people to swoop in and help.

But there’s a profound shift underway in both disability politics and policy to a person-centred and rights based approach in service delivery — rather than a one sized fits all charity model. For decades, the social model of disability has become much more widely accepted among the disability community. This model understands that it is society which disables people, through lack of access and discrimination. The social model says that disabled people have to be part of the campaigns that involve them; it rejects campaigns that encourage able-bodied people to do things disabled people can’t, with the aim of ‘fixing’ them.

That’s why disability activists, including people with cerebral palsy, are now calling for CPA to end Steptember: because the idea of a campaign about disability that disabled people can’t participate in is insulting; and because disabled people don’t need fixing.

These activists believe that campaigns like Steptember need to be replaced by campaigns that include people with disabilities, and centre on helping them live a better life rather than ‘fixing’ them. Disabled people have just as much right to a good life as everyone else, and shouldn’t have to rely on charity for what they need. But it’s been this way for a long time, and change can be hard.

What’s So Wrong With Raising Money For Disabled People?

This is a good question: it depends on how you do it.

The charity model — be nice to the poor, crippled people over there — reinforces the idea that disabled people are separate from ‘normal’ people; and that being disabled, or ending up in a wheelchair, is a terrible fate to befall someone.

Rayna Lamb is President of Women with Disabilities Australia, and lives with cerebral palsy. “When I started using a wheelchair, strangers were, ‘Oh no, that’s terrible’,” she says. “But my friends were pleased because I could move around and I was obviously in less pain. I can be part of society if I am on wheels, after a lifetime of being told the opposite.”

The group advocating to End Steptember have highlighted why this kind of charity campaign is problematic: because it “segregates and isolates us from others, not only via this campaign but by reinforcing [certain] stereotypes and attitudes.”

The Steptember campaign has used a variety of images and videos in their promotional material that have caused great offence for disability activists, such as this post of a TedX talk about how sitting is the new smoking.

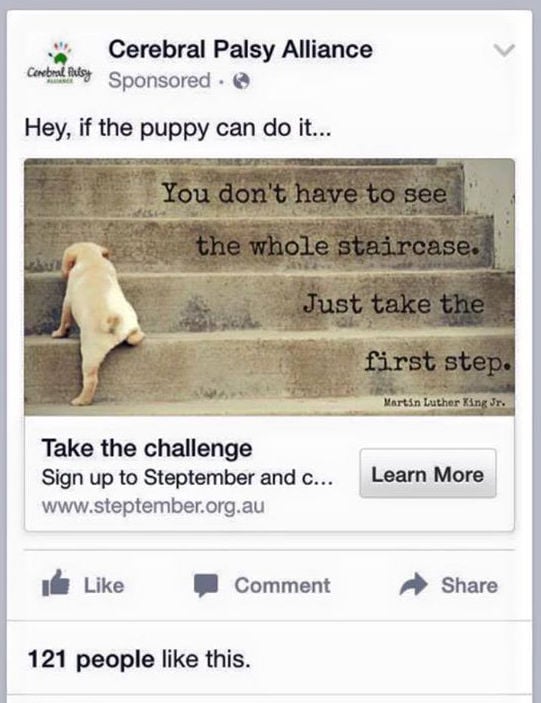

Another Facebook ad has featured an image of a puppy climbing stairs with the tagline “Hey, if the puppy can do it…”

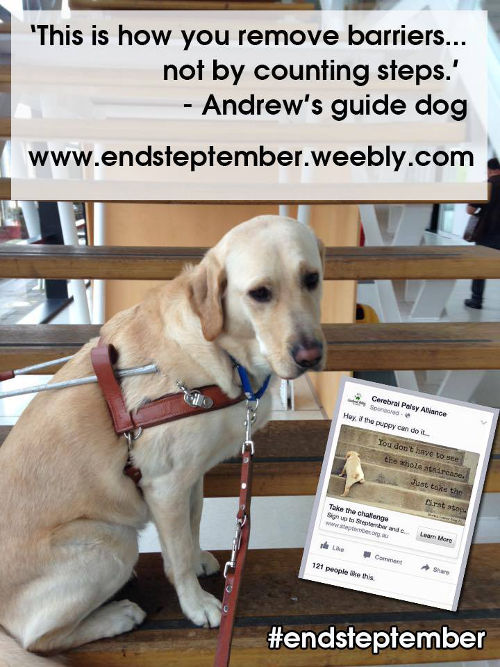

End Steptember activists have responded with images that critique the campaign for its focus on able-bodied people, and highlight how inaccessible steps are from them.

–

Disability activist Jarrod Marrinon also finds images like those used by Steptember distressing. “When I was the same age as the kids in this campaign, if I was getting messages that being in a wheelchair was the end of the world, that would be terrible.”

Marrinon has been posting videos on Twitter and Facebook, asking friends and support workers to join in the campaign against Steptember.

I am not lazy. I am not a dog. End #steptember now! @CPAllianceAU @SteptemberAU pic.twitter.com/2d3k2VFKrG

— Jarrod Marrinon (@jarrodsopinion) July 28, 2015

Jax Jackie Brown is another disability activist who has issues with the framing of the campaign. “[It’s positioned] as if cerebral palsy impacts on my life only in a negative way. This is seriously problematic, from a pride and disability rights perspective.”

Brown describes getting to the age of fourteen, and realising that her cerebral palsy was never going away, despite all the therapy that had been aimed at ‘fixing’ her. “How does a young person start to think about themselves in a way that isn’t negative? This campaign doesn’t teach me how to manage my body, or how it actually moves.”

But Claire Moore, the Head of Communications at the Cerebral Palsy Alliance, rejects this criticism. “We greatly believe that Steptember helps. To engage people who aren’t touched by disability, a hook is needed — often paired with an activity that poses some self-interest,” she explains. “The concept of health and wellness is a huge issue for all Australians, able or disabled. [With this campaign], an individual will initially think, ‘What a great idea – let me get a team together and we’ll get fit together’. However, during the four-week period, they’ll come into contact with the issues facing children and adults with a disability, and have a much better idea of how they can contribute to making our society a better place for all.”

But this raises even bigger issues for disability activist Samantha Connor. “That worries me a lot — because the first time [this individual] may meet a disabled person, they’re doing something for them, not with them. That sends a clear message that we are helpless and pitiful recipients of charity, not people who can work alongside them, play alongside them, live alongside them; that we are to be done to and for, not with.

“We want rights and respect, not charity and pity.”

Nothing About Us, Without Us

Another key criticism of Steptember is the lack of involvement of disabled people in the design and implementation of the campaign.

Claire Day, from CPA, tells me there is only one campaign manager who runs the Steptember campaign. “She doesn’t have Cerebral Palsy, however with representation from across the organisation, a good consultation has occurred and will continue to occur.”

But for some, this isn’t enough: “We need to have people with cerebral palsy involved in every part of the campaign,” says activist Phineas Meere, who has cerebral palsy. “From a marketing perspective, sure, little kids getting wheelchairs sells — but adults getting on with their lives don’t seem to.”

Everything Old Is New Again

There’s a long history, both here and overseas, of these kinds of charity campaigns being challenged by people who have the disabilities they are aiming to help. In Australia in the 1970s, Lesley Hall led protests in Melbourne against the Miss Australia pageant, which raised funds for the Spastic Society — as did Joan Hume in Sydney.

In the US, the so-called ‘Jerry’s Kids’ have campaigned long and hard against the telethon hosted by Jerry Lewis. Again, the problem is not in the fundraising itself, but in the portrayal of disabled people as broken objects of pity.

Sarah Barton, from Fertile Films and Disability Media Australia, is working on a film history of the disability rights movement, and has recorded activists talking about protesting against charities in Australia.

Here, Lesley Hall is describing how she and others smuggled placards into the Miss Australia awards, then stormed the stage:

Lesley spoke to the Sunday Press in Melbourne at the time: “The Miss Victoria Quest emphasises the charity ethic. That people like us are to be pitied and given handouts. Well, we are tired of discrimination and pity.”

The concerns raised about charity model fundraising events back then sound just as relevant today. And Rayna Lamb says, campaigns like this had a huge impact on her as a child. “When I was about twelve, my mother made me go door-to-door to raise money for the organisation I got some services from, the Crippled Children’s Society. One old lady said, ‘There but for the grace of god go I’, and donated. This told me that I was this pitiful, pathetic creature who exists so that people can feel sorry for her.”

This is not the first time these concerns have been raised about Cerebral Palsy Alliance campaigns, either. In 2011, they released ads that discussed the burden of cerebral palsy.

At the time, Todd Winther, who has cerebral palsy, hit back on ABC RampUp: “I’m offended by the advertisement on a personal level, because it suggests that I cannot contribute to society in any meaningful way; that I do not have any positive experiences in my life,” he said. “I am merely a drain on my family and caregivers, because it is all a one way relationship; I am a responsibility to be endured, and not a human being.”

Grit Media, a disability-led production company, produced this response, raising awareness about ‘condescending tools’.

–

The disability rights movement has has long insisted that disabled people must have a seat at the table, and not be the object of demeaning charity campaigns. These days, disabled people are front and centre of campaigns about rights, discrimination and accessibility. Isn’t it time that fundraising campaigns caught up?

President of People with Disability Australia Craig Wallace says, “As disability rights advocates we already know it’s a steep climb, whether by step or ramp, to make inclusion, disability rights and pride a reality. Steptember indicates that the CP Alliance have yet to even mount the curb.”

–

El Gibbs is a writer with an unhealthy interest in Senate Committees. She’s on Twitter at @bluntshovels and blogs at Blunt Shovels.