Controversies And All, Is ‘Moana’ The Ultimate Blueprint For Diversity In Film?

We speak to the Polynesian cast and crew behind the movie.

Moana is being hailed as a Disney masterpiece and already smashing box office records in the US. But the arrival of the big mouse’s first Polynesian princess hasn’t come without its controversy.

First, there was backlash about the physical characteristics of Maui — the demi-God voiced by Dwayne ‘The Rock’ Johnson — adhering to cultural stereotypes of obese Polynesians. Then there was the ill-conceived ‘blackface’ Maui bodysuit, which was quickly pulled from shelves. While those considerable issues might have been enough to sink other family-friendly blockbusters, the film has soared over the crest of expectation like its plucky teenage heroine does the waves of the South Pacific Ocean. And a big part of that is down to the people who created her.

Moana is directed, written and produced by the filmmaking duo of Ron Clements and John Musker. They’re responsible for saving Disney animation from the brink of destruction in the late ‘80s with The Little Mermaid in 1989 followed by Aladdin in 1992 and Hercules in 1997. They stumbled with Treasure Planet before finding their feet again with the near-perfect Princess and the Frog in 2009, which coincidentally gave Disney its first African American princess in Tiana.

Ron and John are two old white guys and they’re receiving a lot of the acclaim for Moana, which is one of Disney’s most diverse and progressive films to date. But there are many brown people who breathed life into this story of Polynesian myths and legends, and some of the film’s biggest victories land squarely on their shoulders.

The Oceanic Story Trust

Disney has definitely fucked up in the past when it comes to representing non-alabaster cultures on screen (see: Pocahontas), but they’ve also succeeded (see: Lilo & Stitch and Mulan). The key difference between their triumphs and failures, they seem to have realised, is making sure the kinds of people in their stories are also involved in the film in as many ways as possible.

Moana had the largest amount of time and money committed to any non-white story in Walt Disney Animation’s history (the film took between four and five years to make and cost $150 million). To ensure they were getting as much right as they possibly could, they also created the Oceanic Story Trust — an advisory group providing cultural input into the film’s production.

“We have a long history and knowledge and mana,” says Tiana Nonosina Liufau, who was one of the experts recruited for the group and the choreographer of all the dances and character movement you see in Moana. There are other consultants too, she says, covering everything from “tattoo and voyaging” right through to “legends and myths”.

“I think for me, when I heard there was going to be a Polynesian film, it was important that there were people involved from the source who are very well-versed or had dedicated their lives to some facet of Polynesian culture — whether that be language or body art or textiles or dancing.

“I’m just extremely impressed with the team this film has. It’s exciting because, for a lot of people, it might be their first introduction to Polynesian culture. It’s humbling because everyone I’ve met on the team has taken so much time and energy and effort and heart to understand a lot of the essence of our Polynesian cores and values.”

Ron, Jon and a crew undertook an initial research trip to Samoa, Tahiti, and a number of the other 1,000 islands that make up Polynesia to assemble this team, and the Trust worked on the film from initial concept right through to story and post-production. This influenced a countless number of decisions. It was the Oceanic Story Trust, for instance, who vetoed the original design of Maui which had him as a bald demi-God — something that was jarring to several experts in the trust as mana (power) is held within the hair.

With thousands of years worth of culture, history and mythology to draw from, Tiana understands the film isn’t going to please everyone. Her hope, however, is that they tried their absolute best to make Moana reflective of the Polynesian people.

“What would be super important for the audience to take away from this film — and for me as a dance teacher — is that people understand that our movement is more than aesthetically pleasing,” she says.

“The most important thing is that it tells the story, it perpetrates the teachings of our ancestors, it mimics mother nature, the ocean, fire, land, animals, how our body is only secondary to the poetry, to the text. That’s what really important to me.”

The Cast

Although much of the character concept art had been loosely decided upon beforehand, animators at Disney didn’t officially begin the process until they had a voice to animate to. These actors breathed enormous life into Moana’s cast of characters — from Dwayne ‘The Rock’ Johnson (who hails from Samoa) to Moana herself (Hawaiian teenager Auli’I Cravalho in her first screen role).

Yet it’s the Kiwis who really steal the show: Temuera Morrison joins the long list of formidable Disney dads as Chief Tui, and Rachel House who you probably best know from the films of Taika Waititi (“no child left behind”) stars as Gramma Tala. House brings across all the magic and humour that’s usually enthused into her live-action work, becoming the wisdom and wackiness that fuels Moana’s dreams.

Flight of the Conchords’ Jemaine Clement is another scene-stealer, at one point even getting his own glam rock solo. For the Kiwi native of Maori heritage, Moana was an extension of something he and Waititi had tried to do over a decade ago with their award-winning stage show The Untold Tales of Maui.

“I know that some [Polynesians] think it’s really cool, and some will be watching it with crossed arms going ‘okay, let’s see how they do this’,” says Clement. “Even when Taika and I did our Maui play — a lot of Maori films and plays are very serious and we were doing something that wasn’t — it had a lot of jokes in it. At first when they heard we were doing a comedy about Maui they were suspicious, they were telling us we shouldn’t do it. And then when we did it, those exact same people were like ‘this is the kind of thing we should be doing’.

“A lot has been said lately about representation on film and I think it’s going to be really cool for Polynesian kids to see some Polynesians heroes.”

Music sits at the core of every Disney princess movie and Moana’s soundtrack is just as multicultural as its cast with the trifecta of talent: Lin-Manuel Miranda, Te Vaka and Mark Mancina. While Mark brings the Hollywood polish and experience gained from working on blockbusters for decades, it’s Lin-Manuel and Te Vaka’s collaboration that shines through.

Te Vaka are the bar-setters when it comes to contemporary Pacific music and the New Zealand-based group fuse the modern with the traditional in a way that makes the soundtrack — from the introductory numbers through to the centrepiece ‘How Far I’ll Go’ — feel contemporary while acknowledging everything that has come before.

The Crew

For story artist David Derrick, working on Moana was a dream project. Sure, he’d been a part of blockbuster animation productions before (namely Rise Of The Guardians and How To Train Your Dragon) but Moana was the job of a lifetime.

“Part of my ancestry comes from Samoa, so for me I had to go back to Samoa when I was working on this film with my family — on my own time and dime — and just immerse ourselves in the life and culture,” he says.

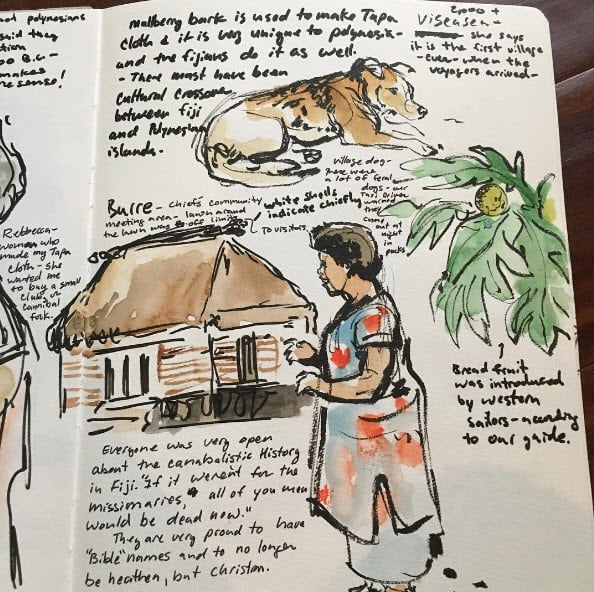

Derrick filled notebooks with drawings and notes as he documented his time back home and when it came round to animating the film, he wanted to infuse his culture into the very DNA of the movie. One of the ways he did that was slipping his grandfather’s Tapa — a treasured Samoan barkcloth — into the movie (keep your eyes peeled for a scene where Moana is walking through her village and a group are folding a large piece of material).

Yet for Derrick, who is a father himself, Moana represented more than just where he’s from: he wanted it to represent where his future was going.

“Moana doesn’t wait for anyone to rescue her,” he says, grinning. “But I’m totally biased because I feel like she embraces a lot of our best qualities. You know, I went and bought the doll for my daughters a few weeks ago. She’s so beautiful and great and I put it up on my Instagram, like, she’s an action hero! This is an action figure, not a doll — she’s a warrior.”

A photo posted by David Derrick (@davederrickjr) on

Zootopia director and writer Jared Bush had a big 2016, wrapping up his animated feature and jumping straight onboard to screenwriting duties on Moana. He echoes Derrick, emphasising the importance of both the film’s cultural context and feminism.

“We wanted to evolve the concept of ‘princess’ for this movie,” Jared says.

As millions flock to the cinema to meet this latest brown version of a Disney hero, it seems safe to say they’ve succeeded.

–

Moana is out in cinemas on Boxing Day.

–

Maria Lewis is a journalist on The Feed SBS and author of the Who’s Afraid? novel series available worldwide. She’s also the co-host and producer of the Eff Yeah Film & Feminism podcast.