‘Citizenfour’: The Edward Snowden Documentary You Need To See

Director Laura Poitras doesn’t just document the story of Edward Snowden, but actively participates in it.

That’s pretty much the overriding feeling one gets from watching Citizenfour (2014) — likely to be the most important documentary of the year, and maybe next year too.

With this film — which just came out in the US, but is TBC in Australia — director Laura Poitras doesn’t just document the story of Edward Snowden, whose whistleblowing revealed classified surveillance information about the operations of the NSA, but actively participates in it as it unfolds.

“From now, know that every border you cross, every purchase you make, every call you dial, every cell phone tower you pass, friend you keep, article you write, site you visit, subject line you type, and packet you route, is in the hands of a system whose reach is unlimited”, reads one of the many emails Snowden sent to the Oscar-nominated director before filming began. “I ask only that you ensure this information makes it home to the American public.”

This top-secret collaboration between the film-maker and her protagonist lends the film a unique quality that separates it from a mere segment of Four Corners drawn out to feature length. Produced by Steven Soderbergh, and featuring a bass-rumbling music score that utilises Nine Inch Nails’ Ghosts I-IV, this is essential viewing — and hopefully those who need to see it do.

Anybody interested in politics should be following the world of documentary filmmaking right now. It’s an exciting time for the genre that, like, Citizenfour, has found its filmmakers actively participating in the very revolutionary acts they are documenting. Silvered Water, Syria Self-Portrait (2014), for instance, documents the Syrian revolution through the assemblage of over a purported 1000 individual videos filmed by Syrians on their mobile phones and uploaded to YouTube. One scene shows the director’s camera being stolen, only to have the thief be shot minutes later on the street by the military.

In Citizen Four‘s opening sequence, it is revealed — through emails, encrypted and decrypted on-screen — that Snowden deliberately targeted Poitras, figuring she was most adept to handle the task of documenting his act of governmental defiance. Journalists Glenn Greenwald and Ewan MacAskill join them in a top secret Hong Kong hotel as they plan the leaks and subsequent interview that is to be released to the media. “My personal desire is that you paint the target on my back,” Snowden tells Poitras, eager to inform the world that it was he and he alone who took the initiative to tell the world about the NSA’s global spying ring. True to form, the government were soon swarming on Snowden’s girlfriend and family. Poitras worked on the film in Germany to avoid American visa issues. Greenwald’s partner, David Miranda, was even detained at Heathrow Airport in 2013 under the guise of national security.

Citizenfour is perhaps the boldest move by a documentarian since Iranian filmmaker Jafar Panahi, placed under house arrest for propaganda against the Iranian government, had his housebound doc This is Not a Film (2011) smuggled out of the country on a flash-drive hidden inside a cake. For those who hold a (perhaps naïve) respect for politicians, the film will play like a nightmare. Snowden himself certainly tries to drive the message home, claiming any technological device within reach is likely to be hacked or bugged, covering himself in a blanket to use his laptop, playing up the potential insidiousness behind a hotel fire alarm test, and remaining secretive when relaying information late in the movie about who in Russia is giving him protection (he is smuggled out of the country by Julian Assange, who has a brief cameo).

In America, the movie is being released the week before Halloween, and is likely a hell of a lot scarier than anything Annabelle (2014) or Ouija (2014) have to offer. A.O. Scott of the New York Times calls it a “tense and frightening thriller that blends the brisk globe-trotting of the Bourne movies with the spooky atmospheric effects of a Japanese horror film”, while Dan Walber of Nonfics labelled it “not entirely unlike a superhero movie”. David Edelstein even goes so far as to suggest you “don’t buy your ticket online or with a credit card.” Filmmaker and Bush administration rabble-raiser, Michael Moore, hailed the film as “brilliant, damning.”

World premier of Edward Snowden doc, CITIZEN FOUR, just ended to a long and rousing standing ovation at Lincoln Center. Brilliant, damning.

— Michael Moore (@MMFlint) October 11, 2014

This film doesn’t tell the entire story. It doesn’t go into allegations that Snowden deliberately sought out a position with the NSA-affiliated company Booz Allen in order to “get access to the crown jewels, the lists of computers in four adversary nations – Russia, China, North Korea and Iran – that the agency had penetrated.” Nor does it detail the many more documents, believed to be upwards of 1.5 million level 3 classified, that were leaked by Snowden after the events of Citizen Four. The film doesn’t attempt to probe the hows or the whys regarding the NSA’s actions — or how governments around the world, like Australia, utilised their processes to their advantage, and even against their own people.

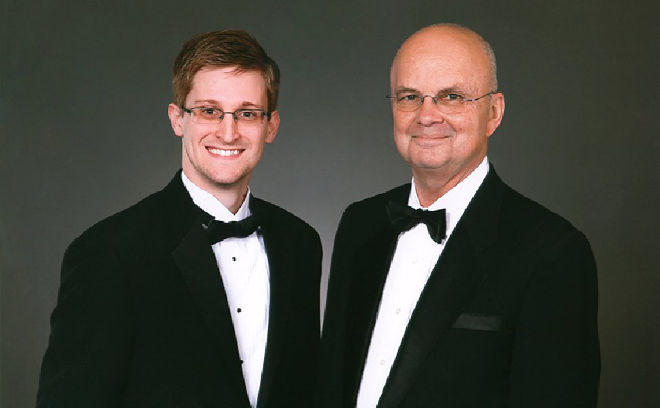

And personally, I would have liked to have known how Snowden felt when he took this photograph with NSA chief General Michael Hayden in 2011.

In spite of all that, Citizenfour is unmissable: a key document in the story of the NSA that future generations will find not only invaluable, but perhaps even unbelievable.

And the moment that reveals Snowden as a Selena Gomez fan is priceless.

–

Citizenfour is out now in America, with an Australian release date TBC.

–

Glenn Dunks is a freelance writer and film critic from Melbourne, who is currently based in New York City. He tweets from @glenndunks.