Why Australia Won’t Face Up To A Problem Like Chris Lilley

"To admit that Lilley is guilty of a racist act of cultural violence would be to admit that the nation itself is a constantly unraveling act of actual violence."

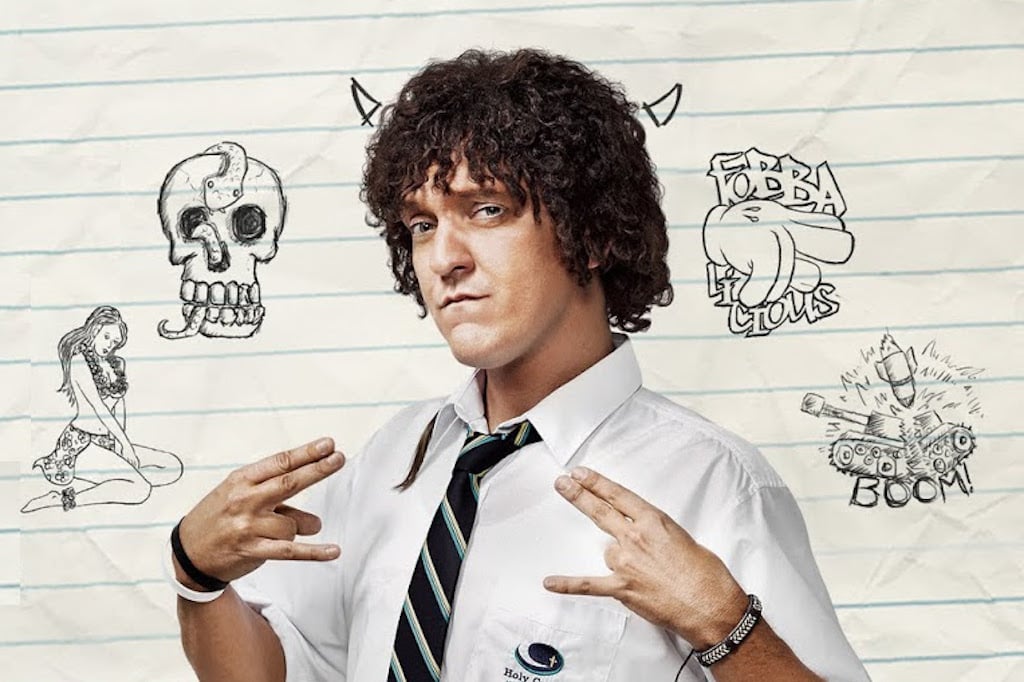

Chris Lilley is a minstrel. Hailed as a genius actor, a startling mimic, an enigmatic artist, and showered with Logies, Lilley is often seen as a wunderkind who took the Australian TV comedy landscape by storm. In the mid-2000s, he elevated social satire to prestige dramedy, capturing the hearts of fans and critics by “going there” and distilling the basic essence of contemporary Australia. Or so the narrative goes. Lilley was depicted as a comic savant: an uncanny reflection of a nation undergoing change.

Whether or not you believe all that, he’s also a minstrel. What was often lost in all the fawning and re-runs was an appreciation of this essential fact. Lilley’s comedy was a continuation of a comic tradition rooted in colonialism and slavery, fundamental to the formation of Western entertainment. It was steeped in a violent cultural racism prevalent in countries where the discourse is directed by a national identity which centres on whiteness (see: Australia.)

Yes, Lilley was a genius minstrel, but a minstrel nonetheless.

What Exactly Is Minstrelsy?

More than just blackface (though that’s of course a large part of it), early minstrelsy was comprised of observational sketches and musical numbers, focusing on the lifestyles and culture of American slaves. As Eric Lott argues in his seminal text on the subject, Love and Theft, minstrelsy was “the first and most popular” original form of the 19th Century: it was an act of cultural appropriation, oppression, and fetishisation. Both the American songbook and the American jokebook — the canons which shape so much of pop culture — have their roots in minstrelsy.

It is important to understand the integral role of minstrelsy to modern comedy. The roots of Western standup and sketch are in vaudeville, and vaudeville was rooted in minstrelsy. The Marx Brothers, Buster Keaton, Harold Lloyd, Charlie Chaplin: all minstrels. The most successful comedy show of its time was Amos ‘n’ Andy: two white men approximating black southern slang to garner major yucks. Bugs Bunny was modelled after old minstrel acts. Mickey Mouse’s face intentionally resembles that of a cork-faced minstrel clown, for God’s sake. There’s a reason that minstrel frog was the one that welcomed you back to Looney Tunes: “welcome back n*ggas,” as Dave Chappelle so eloquently summed it up.

The minstrel tradition didn’t really die off in American comedy (overtly) until the mid-1970s, when most of its greats began to die. Simultaneously, black comedy by black artists (many of whose tastes and influences were shaped by the cultural hegemony of minstrelsy) were becoming ‘mainstream’: Dick Gregory, comic-poet of the black comedy circuit aka ‘the Chitlin Circuit’ (and creator of the standup album), was no longer a fringe act. Richard Pryor was starring in films and filling stadiums. Eddie Murphy’s Raw wasn’t far off. The fate of minstrelsy was all but sealed by the 1990s, where it took on subtler more insidious forms. At least in the US.

In a country where the popular culture is often driven by the exploitation and appropriation of black culture, the demise of overtly racist forms was all but inevitable. In countries like Australia however, where a white majority views any outside perspective as a form of exoticism in a similar vein to audiences of the 19th century, the tradition and tropes of minstrelsy (blackface, appropriation) go largely unchallenged.

Blackface was not an irregular occurrence on Australian TV, even in the 2000s. With the taint of slavery shifted to that of colonialism, the way in which we ‘appreciate’ minstrelsy is slightly different to our US cousins. We are still the nation of the Golliwog and Hey Hey, It’s Saturday. We are one of the few places where the merits of blackface are earnestly debated in the press. Our TV is rife with British imports, which are in turn rife with blackfaced sketches that could be straight out of a circus tents circa 1895: Little Britain, Katherine Tate, and Come Fly With Me all cribbed heavily from the minstrel textbook.

It’s important to understand that Chris Lilley doesn’t exist in a vacuum. The TV culture that allowed Bert Newton to call Muhammad Ali “boy” at the 1978 Logies, allowed Chris Lilley to be showered with accolades for his ‘impersonations’ of black bodies. It will be debated within certain contexts in Australia, the merits will be weighed, critics (particularly those of colour) will be dismissed as hysterics and wankers, and two weeks later your cousin’s mate Devon will turn up to his 21st in blackface as Public Enemy (this happened to me).

The narrative never really shifts in Australia: to admit that Lilley is guilty of a deeply racist act of cultural violence would be to admit that the nation itself is a constantly unraveling act of actual violence.

That admission will never come. White Australia may confess Lilley is “offensive”, but hey, he’s also pretty funny, right?

Is Chris Lilley Funny?

That’s a tough one to answer, hey? Comedy is, after all subjective (or so we are told). As a 14-year-old white boy in a public school, I was Chris Lilley’s dream demographic. On top of that, all I wanted to be was a comedian: my repertoire was heavy in impersonations of cultural stereotypes, my peers, my teachers, and John Howard.

When I first saw We Can Be Heroes I thought “yes, this guy gets it: it all can be skewered”. With Summer Heights High he seemed to reach another plateau: “Mr G is Mrs Clements!” I thought, while high-schoolers a nation over said variations of the same. He was an enviable mimic, and one whose comedy was steeped in the dry pathos of a form that had gone from Spinal Tap, to Working Dog, to David Brent, and beyond.

That dry mockumentary style gave the character’s a weighted authenticity that would otherwise be absent. It’s not racist, you’d tell yourself. Jonah is fleshed out: look at this moment when he is sad about failing school. If Lilley was truly racist, Jonah wouldn’t be depicted as vulnerable. This is funny, we said, but it’s sincere.

Friends, God help you if you laugh at the same things as a 14 year old when you are anything but. God help you if you can’t peer through the fog of nostalgia at a cultural artefact and admit to yourself “gee, that’s actually a little bit shit, and a lot problematic.”

When Chris Lilley debuted the character S. Mouse in 2011’s Angry Boys, the Australian media was filled with milquetoast thinkpieces that dared to ask: “Is S. Mouse Racist?”. The answer to seemingly anyone who wasn’t white and Australian was: of fucking course. S. Mouse was a black rapper. Australians weren’t really bothered with the racism inherent in the depiction until someone showed Lilley’s shtick to a bevvy of black American performing artists, who all had the fair reaction of: what the fuck is this racist shit?

Enter the free-speech brigade, defending Lilley’s right to touch on all and sundry because he is a ‘satirist’. It’s a predictable response. What’s more interesting in the handwringing of the cultural critics of the ‘left’, is the desperation to align Lilley’s portrayals of POC with what they perceived as his genius. Gradually, S. Mouse was seen as permissible but also the limit: Lilley’s mockery of the gay, those with intellectual disabilities, the poor, and the black was fine, but to a point. Bert didn’t mean to call Ali boy, guys. Not like that.

Jonah From Tonga received criticism, but always with equivocation. Almost all critics posited their thoughts along the lines of “genius or racist?”, condemning Lilley’s shortcomings while praising what his attempt to engage in “some healthy introspection”. He was nominated for Most Popular Actor at 2015’s Logie Awards. Our neighbours in New Zealand just banned Jonah From Tonga for its harmful depiction of cultural stereotypes. Why do you think that didn’t happen here?

Australians will more readily admit to being irked by minstrelised depictions of African-Americans than those of indigenous peoples, because the latter asks you to acknowledge a dark truth about our nation’s identity. White Australia favours the cultural labour of American blackness over Australian blackness, not just because we are a nation of middle-class white kids raised on hip-hop. We are founded on genocide, and we persist through genocide. Minstrelsy and blackface have always been an important part of this narrative of violence. It was both a way of humanising and cartoonifying the victims of colonial oppression: it allowed Victorian audiences to say ‘they’re foolish fellows, not unlike us, yet not like us at all’. Therein lies the love and the theft.

In Australia, minstrelsy of indigenous peoples cannot be separated from centuries of violent colonial policy. Jonah is the happy savage, the Uncle Tom, the Uncle Remus, Amos and Andy, and the ‘empathic depiction’ of acceptable post-colonial blackness. He is a bizarre character for a middle-aged white man to play for many reasons, but at the root of it is the violence that the character is symptomatic of, and permits.

Blackface only exists in a vacuum to those who aren’t harmed by it.

People who defend Lilley, and characters like Jonah bring up two points. The first is that he fleshes out these characters, and makes them more than stereotypes. Though I’d argue he doesn’t. The introspective moments of characters like Jonah, S. Mouse, and Ricky Wong (good grief!) are sentimental, sure, but ultimately insincere. Minstrelsy and real empathy can’t truly mix.

Characters like Remus and his various incarnations were given tragic soliloquies too. They lamented the plantation, the slave trade, the cruelty of “massa”. Black comics who adopted the form such as Bert Williams and Bill Robinson performed blackface to black audiences as a way of satirising their own culture. But still, people act as though Lilley invented the idea of rounding out a 2D depiction with moments of quiet reflection.

Pull back the curtain, and Oz is wanking into a sock: critics who act as though Jonah brings a nuanced appreciation of the troubles of the young, poor, and brown are merely attempting to extricate themselves from an act of violence whose DVD covers will wear snippets of their praise like Bill Leak captions — available at all good ABC retailers.

When I think of Lilley defenders (and I was once one of them) I think of seminal music critic Nick Tosches who, like Eric Lott, wrote one of the great texts on the legacy of blackface. Tosche’s Where Dead Voices Gather (2001) is an elegiac reappraisal of the legacy of blackface in what he perceives to be the age of political correctness, done through the prism of his geekish hunt for obscure recording artist/minstrel Emmett Miller.

Tosche makes the most eloquent defence of the form available in print, but what begins as a startling reappraisal of Miller’s performing genius, ends as an uneasy rant about PC censorship and the gravity of cultural appropriation. Tosche argues that the problematic nature of minstrelsy does not discount the quality of the art, and he argues it very well. But ultimately, by separating both the racist and violent connotations of the form from the performer and their body of work, the work itself is not truly appraised. Blackface only exists in a vacuum to those who aren’t harmed by it.

I’ll admit that Lilley is a good minstrel, if nothing else. I don’t think minstrelsy has a place on Australian TV in the 21st century, but I understand that some TV executives and those on the Logies board of directors think otherwise.

For those who are unconvinced, I’ll leave you with a simple test. Watch Chris Lilley’s work with a friend who is a person of colour. Watch Jonah with a Tongan friend, S. Mouse with a black friend, Ricky Wong with an Asian friend, Mr. G with a gay friend, and stew in the tension that rises up between you. Heck, do as I did recently and re-watch Ja’mie with a 13-year-old girl, and watch her cringe as she says, “this guy is kinda a perve” as Lilley attempts to approximate her body.

Minstrelsy, in the end, is the art of possession. Is it really unsurprising when the possessed want the devil out?

–

Patrick Marlborough is a writer and comedian based out of Fremantle. He tweets at @Cormac_McCafe.