Nuns, Heroin & The Daily Tele: A Short History Of Australia’s First Supervised Injecting Centre

Today, heroin is something you’re most likely to bring up in an English tute on Trainspotting. But in the nineties, it was a headline-grabber, totemic of disease, terror and death. In the fevered imaginations of Australians, the apocalypse horseman AIDS rode on the back of every needle.

A few years earlier, prime minister Bob Hawke had wept on national TV as his daughter lay wasted in hospital from addiction. By 1999, the epidemic had reached its peak, with a record 1,740 deaths from fatal drug overdoses – 1,116 of which were caused by heroin.

Nowhere was the crisis so bad as New South Wales. In Cabramatta and Kings Cross, ambulances wailed to parking lots and apartment stairwells, as locals grimly scanned footpaths for needles. Police responded by mounting an aggressive crackdown, arresting 300 each month that year for use and possession. They’d even show up with the ambulance at a triple-zero call.

But why call for help if you thought you’d get arrested? Something had to change.

An Act Of Compassion

In an act of civil disobedience, a cadre of nurses, doctors, users and their parents set up a ‘Tolerance Room’ in Wayside Chapel, where users could safely inject. The group hoped to convince then NSW premier Bob Carr that prohibition, intimidation tactics and the brute force of the law weren’t going to cut it. Compassion might.

Following a drug summit recommendation, and despite the condemnation of the United Nations, Carr did end up approving what would be Australia’s first medically supervised injecting centre (MSIC). Set up by St Vincent’s Hospital, it was to be run as an 18-month trial in the epicentre of the crisis, Kings Cross. Here, among professionally trained staff, users could self-administer with sterile equipment. Instead of a jail cell, some of the community’s most marginalised and vulnerable found sanctuary and help.

It was a landmark decision that took a lot of political guts. Like pill testing today, it was a controversial “lesser of two evils” approach – fertilised by desperation, but built on pragmatic, forward-thinking principles that put human life first. The Drug Misuse and Trafficking Act had to be amended to make its operations legit.

Once opened, the facility would be the first of its kind in the southern hemisphere and the first in the English-speaking world. The first clinic in the world was opened in Switzerland in 1986.

The Sisters of Charity Health Service, a Catholic charity, had been invited by the government to run the facility. They hated everything to do with drugs, drug-taking and drug-trafficking but decided to accept.

Nope, sang the Vatican from across the seas. Cardinal Ratzinger – later to become Pope Benedict, the one who gave up the big hat – threatened to blacklist the nuns if they took part in the trial. To do so was to cooperate “in the grave evil of drug abuse,” issued the statement from Rome. Nuns helping users shoot up was hardly a notion without scandal for the Roman Catholic HQ; even if, as one Sister said, it was what Jesus would’ve done.

An Australian First

In 2001, the centre did open, but licenced under a ministry of the Uniting Church in Australia instead. Like the hundred or so others around the world, the clinic was and remains a success for users and the community. Eleven evaluations and reports from five different agencies (including the National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre) found the facility had largely positive or non-adverse impacts on users and the community.

About 200 injections are supervised daily; 6000 overdoses have been managed on the premises without a single loss of life, and many frequent users have accepted referrals for treatment and rehabilitation. Over three-quarters of local business owners and residents are supportive, too.

It soon came to light the needles were dumped as a stunt to discredit the centre.

The Pope wasn’t the only critic though. Particularly during the trial’s early years, commentators, religious groups, politicians and citizens rallied to bring it down. Using millions of tax dollars to fund a junkie’s playground was a policy of a maniac, they said. What were they on? Concerns mounted when ice came on the scene, with staff having to be retrained to handle symptoms of psychosis and aggression.

Many also said that the successes the clinic claimed were overstated. With increasing prices and lower purity turning the noughties into a ‘heroin drought’, of course there were fewer needles being discarded on the street. Of course you saw fewer people shooting up.

True to character, the Daily Telegraph was so eager to dish out moral jeremiads, it forgot what proper journalism meant. In 2006, it published photos of 100 “potentially deadly blood-tainted needles” in a bin near the clinic, using them as evidence to demand immediate closure. Not ours, said the clinic’s director coolly. It soon came to light the needles were dumped as a stunt to discredit the centre.

Despite such attacks, the clinic endured. After repeated extensions of the trial, in 2010 NSW finally agreed it could run on an ongoing basis.

If They Work So Well, Why Aren’t There More?

Given the evidence of medically supervised injecting centres’ success, why aren’t there more? It was only last year – following years of campaigning – that Australia’s second MSIC trial was approved in North Richmond, Victoria. It came only after public pressure forced an election promise backflip from premier Daniel Andrews, too. Within three months, 140 people had been treated for overdoses at the centre on Lennox street.

“This was [set up] to save lives, every indication is this facility is saving lives,” said the mental health minister, Martin Foley. Yet it’s set to be scuppered if the Liberals win the next state election.

Alex Wodak, President of the Australian Drug Law Reform Foundation, and one of the renegades who set up the Tolerance Room in 1999, believes there should be a network nation-wide.

“Overdose deaths have been increasing in Australia in recent years,” Wodak told VICE. “Where you need them, is where you’ve got a huge drug market that spills over into the rest of the community. If there’s not a medically supervised injecting facility available, they’ll inject in the streets, lanes, parks and supermarkets, where other members of the community have to see somebody shoving a needle into their arm.”

Ironically, Wodak was invited to speak at the Vatican last year on his views on drug reform.

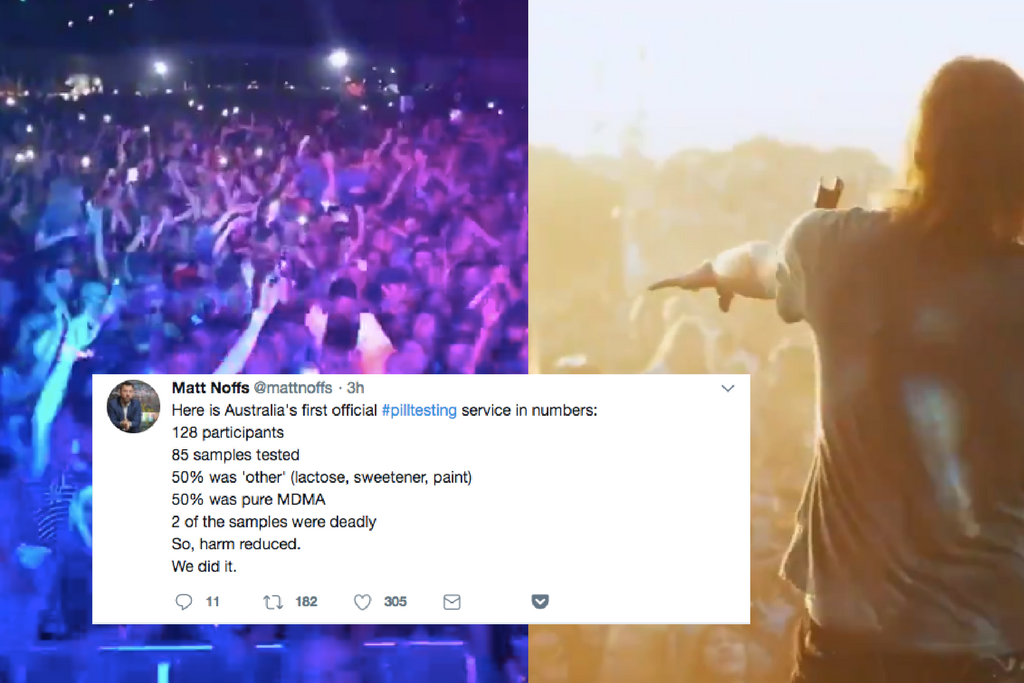

Today, it’s pill testing that’s dominating headlines. Wodak is a vocal supporter of this measure, too. Recently, backed by former AFP commissioner Mick Palmer, he called for MDMA to be sold over the counter at pharmacies.

The differences between pill-testing pop-up stations and MSICs are significant.

It’s got to be said though: the differences between pill-testing pop-up stations and MSICs are significant. Festival-goers are unlikely to be substance dependent – they want to pop a cap to enhance a good time, not satisfy a terrible, all-consuming need. One does it in a crowd to experience a euphoric connection to others; the other is profoundly alone. One has the freedom to choose, the other does not.

The demographic profile of your average pill-popper and heroin/ice addict is probably pretty different, too.

Still, much like the anonymous 21-year-old wrote after the fatal overdose of a festival-goer at FOMO, people are always going to take drugs. Even if they have full knowledge of the risks, even if their peers are dying from them. Rather than a zero-tolerance policy, which encourages high-risk behaviours, both MSICs and pill-testing are a way to minimise harm through creating more safety and control around drug-taking.

Here’s to hoping that our political leaders have the acumen to recognise that, and the courage to act on it.