Australian Political Satire Doesn’t Go Far Enough

We've got great comedy talent in Australia -- but it's too focused on day-to-day follies to take a critical look at the bigger picture.

In March 1797, Aboriginal resistance fighter Pemulwuy suffered seven bullet wounds after leading 100 men against British soldiers in Parramatta. Local convict satirists sided with Pemulwuy, that evening staging the first ever “Wharf Revue”. Devoted entirely to impressions of Governor John Hunter in different kinds of hats, the show proved disappointing. While the crowd laughed because the hats did look very funny, the chance to expose the injustice of invasion and occupation was squandered.

Was the lacklustre satire at the convict revue to blame for the following two hundred years of massacres, stolen generations, and deaths in custody? Probably. What’s certain is that while Australian satirists are good at ridiculing the day-to-day buffoonery of individual public figures, rarely do they step back and see the forest for the trees.

Systemic satire, on the other hand, is all about the forest: it finds giggles in the social structures and political systems responsible for injustice. But while this kind of satire is popular overseas, and does exist on the fringes of Australian pop culture, we need it to be brought into the mainstream — now more than ever.

–

Two Types Of Satire: Systemic Vs Day-To-Day

1. Systemic Satire

“As men neither fear nor respect what has been made contemptible, all honor to him who makes oppression laughable as well as detestable. Armies cannot protect it then; and walls which have remained impenetrable to cannon have fallen before a roar of laughter or a hiss of contempt.”

– Edwin Percy Whipple, 1871

In stolen moments between serving choc tops, Mr Whipple made some jolly good points. Systemic satire can undermine power structures and awaken citizens to their own manufactured consent within these structures. It can make you laugh at your own exploitation, and then make you angry enough to do something about it.

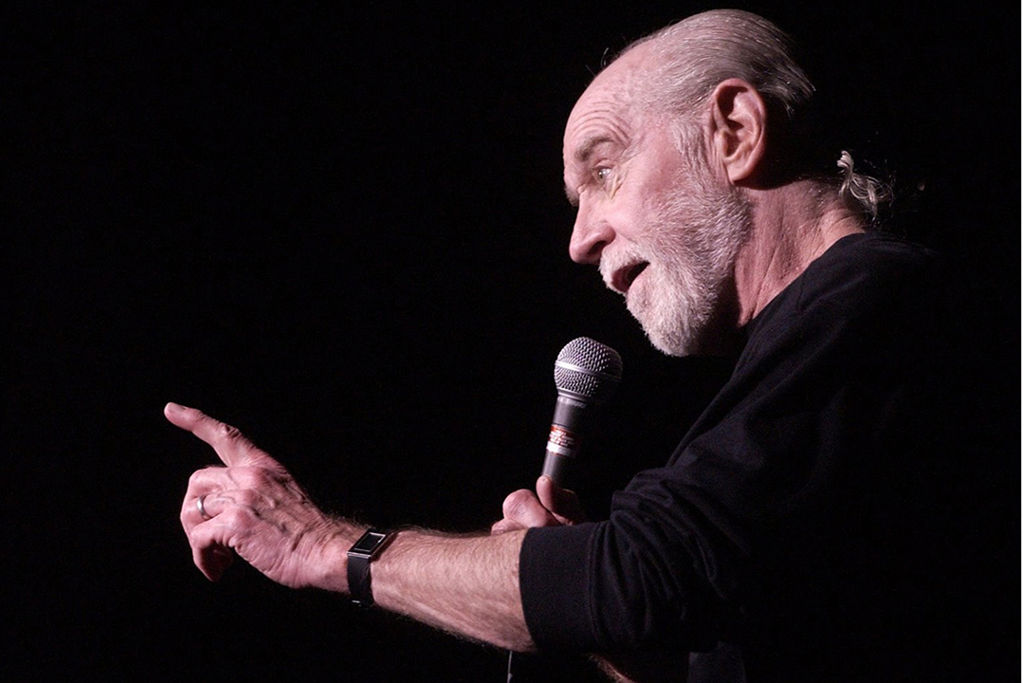

International comics like Stewart Lee, George Carlin and Louis CK play with this kind of satire. In this clip, Stewart Lee takes on misinformed public discussion of Islam:

Lee points to the wilful ignorance underpinning racist attitudes towards Muslims with his anti-Islamic one-liners: “You know, one in two kids born in Britain today is called Muhammad, and that’s just the girls. I’ve done no research.” He observes that “ridiculing individual Muslims” is useful only as a means to win cheap laughs and national popularity, and mocks the idea that we need to balance considered opinions with prejudice.

George Carlin gets at one important cause of this ignorant and racist culture: the corporate ownership of public life.

Carlin touches on corporate control over our land, and our political and legal systems. This control extends to our opinions, which are formed by the mass media. He says the whole US political system is rigged in favour of the ruling classes, who over the past three decades have been rapidly eroding worker’s rights and social welfare. He busts the myth of the American Dream, insisting that an ignorant public culture serves the interests of the status quo. Our owners “don’t want people who are smart enough to sit around the kitchen table to figure out how badly they’re getting fucked by a system that threw them overboard 30 years ago.” Of course there’s nothing new about this line of thinking. But by presenting it as satire, Carlin casts a compelling light across his point, and makes it hard to argue with.

Louis CK goes even further. His gaze extends beyond just the flaws of contemporary culture or the corporate influence upon this culture. He pokes fun at deep cultural beliefs that may explain the environmental calamity facing us today:

For CK, the mess we’ve made of the planet has been caused by the arrogant and misguided assumptions of white people. Such assumptions are beautifully illustrated by the interchange between white settlers and Indigenous peoples in the US:

“You’re not Indians?”

“No.”

“Ahh, you’re Indians.”

From this moment on, settlers “ruined everything” in America, replacing the sustainable practices of Indigenous peoples with the environmentally devastating lifestyle of capitalism. For CK, this comes down to a series of cultural delusions: that we need jobs, so we can get money, so we can buy food. CK’s indignant God makes the point: “I gave you everything you needed, you piece of shit…. Just eat the shit on the floor.” This is not enough for white people, who extract oil because they “wanted to go faster”, and don’t want the corn and wheat God left for them because “it doesn’t have bacon around it”.

Systemic satire like this is not limited to stand-up comedians. BBC comedy series Time Trumpet is a retrospective “documentary” from 2031 about the first years of the 21st century. Its premise lends itself to broad attacks on the tragi-comic social structures of our age. In this clip, the theme is the war on terror:

This episode tackles the production of terror by an alliance of government, the media and the culture industry. Terrorism is not just about real atrocities like the London bombings; it is also a cultural construct fed by politicians, the police, pop culture and the media.

The government fuels public paranoia with extreme restrictions on basic freedoms. Here they escalate from banning rucksacks, to abolishing all forms of transport, to arresting Scary Spice, to strip searching at the ballet and cinema, then ultimately criminalising fear. The police play their part by murdering innocent people, as in the real case of Brazilian Jean Charles de Menezes, shot eight times at a London tube station in 2005. In this satirical version, police “shot a completely naked man because they thought he looked like a van packed with explosives”. They then blew up a bus carrying his family to the funeral because it looked like a rucksack.

1997 UK TV show Brass Eye likewise takes a systemic approach to satire. This clip is from an episode called ‘Crime’:

Brass Eye masterfully skewers the moral panic drummed up by the media on social issues. There is great concern that the UK stands for “Unbelievable Krimewave”; that “marauding criminals” are setting everyone on fire; and that “another estate in Manchester is “turning itself into a gun”.

More than this, Brass Eye exposes a vital deception of our era: that the individual is the sole architect of their own fate. Crime, poverty and unemployment are all caused by bad or lazy people. The fact that millions miss out on quality education has nothing to do with a broken system, and everything to do with character flaws. Solutions rest entirely with individual effort: “Dad unemployed, Mum depressed beyond tablets, you want to help these people, but the truth is they’ve got to help themselves.” If you are jobless, have a mental illness, or live in poverty, it’s your fault and you just need to “try harder”.

2. Day-To-Day Satire

While systemic satirists take a bird’s eye view of our society to make institutional causes of injustice ridiculous, day-to-day satirists target particular individuals — usually using the latest news headlines. This brand of satire is best represented by The Daily Show and The Onion – and it’s this model Australian satire seems to cling to.

Here’s a selection of the best moments from The Daily Show in 2012:

Jon Stewart spends a lot of time focusing on the daft comments of personalities on Fox News and within The Republican Party. The bits here on the “worst President in history”, Clint Eastwood, and Republican delusion on election night are typical. Stewart is not afraid to lampoon public figures on both sides of politics — Obama being a particularly willing participant in his own ridicule. Sometimes individuals take centre stage not to be mocked, but to be praised and enjoyed. Celebrities like Jon Hamm, Will Ferrell and Shaq are a key ingredient of the show’s success. At other times the latest headlines will face scrutiny, as with Time’s coverage of “Animal Friendships”.

The Onion’s political headlines use a similar method, sending up the week’s news events with a focus on particular personalities. Recent articles include: Elite Congressman Trained to Kill Legislation in 24 Different Ways, John Kerry Poses as Masseuse to Get Few Minutes With Putin, and Obama Admits US Hasn’t Been the Same Since Buddy Holly Died.

Day-to-day satirists use this recipe to entertain millions each day, its wild success inspiring similar work all around the world.

–

The Triumph Of Day-To-Day Satire In Australia

Australia has adopted the day-to-day model to great effect. The Hamster Wheel, Mad as Hell, Clarke and Dawe, The Roast, A Rational Fear and The Shovel are all very successful in their own right, each roughly following the same formula: daily or weekly responses to the absurdity of the news. They take the ridiculous actions and comments of obnoxious politicians, celebrities, media commentators and business people, and use them as fodder.

The Hamster Wheel ridicules Lord Monckton:

–

Mad as Hell lampoons Andrew Bolt’s journalistic integrity:

–

The Roast takes on Rudd, Abbott and Palmer during the 2013 election:

–

A Rational Fear mocks Alan Jones’ attitude to women:

–

And here are some recent headlines from The Shovel: Barry O’Farrell Back to Work Already, Bob Carr Just Grateful to Have Been Able to Work With Bob Carr, and Arthur Sinodinos Can’t Recall Whether He Left Stove On.

These satirists also feature pieces around particular issues or policies, but even these issue-focused pieces often rely on attacking individuals over the wider systemic problem. The Hamster Wheel’s piece on gay marriage is a typical example:

The regressive positions of the individuals who are targeted above are obviously absurd; they satirise themselves. We all have a good laugh at the fellow who says “three blokes, two dogs, nothing is sacred after this”, but for much of this clip we’re just laughing at ill-educated members of the general public, instead of the system which moulds them.

This kind of satire is booming in this country, where the dominant approach for Australian comedians is to skewer the particular personas and backward opinions that are making headlines that week. It’s not hard to see why; Tony Abbott’s a goldmine. His courageous quest to find his ladies and manly hunt for a bloke’s question were free kicks for the day-to-day satirist. But can’t we also use comedy to heap scorn on systems and structures, more than individuals and headlines, to rouse a dormant public?

–

For An Australian Satirical Revolution

Although it is more quotidian satire that dominates the Australian landscape, there are examples of systemic satire in the margins of our culture. Occasionally, comedians escape the trappings of weekly news about foolish personalities, to look at the deeper causes of injustice.

For example, the 1986 satirical film BabaKiueria flips the entire history of race relations in this country:

This film is a wide-ranging examination of two centuries of white oppression of Indigenous peoples. It opens with the invasion of white land, BabaKiueria, by Aboriginal people. This is the fundamental injustice at the root of all that follows. The dismissive attitudes of the mainstream are highlighted from the outset when the host asks a punter on the street, “What do you think about white people?”

“White people, you’ve got to be joking.”

BabaKiueria also confronts deeply held beliefs of racial/cultural superiority. The host asks the minister:

“Has the government tried to find out what white people want?”

“Why? I mean, we’re the government. It’s our job to make decisions about what these people want, and give it to them.”

This feeling of supremacy leads to the patronising and offensive idea that oppressed peoples should just buck up and help themselves. According to the police superintendent in the film, it is not radical social reform that will improve the lot of the first Australians. Instead the oppressed minority should just “smile a lot. That’s all it takes. You can do wonders with a smile”.

Aamer Rahman, one half of stand-up comedy team Fear of a Brown Planet, takes this technique of race-flipping global in his bit on “reverse racism”:

Rahman resists the temptation to ridicule individual white people — all too easy given the awful shit we say and do. Instead, he offers a sweeping thought experiment attacking the history of global injustice perpetrated by whites. He narrates the history of invasion, occupation, slavery and stolen resources, as well as contemporary systems that privilege whites at “every conceivable social, political and economic opportunity”. For Rahman, contemporary racism is a product of a dark history of colonisation and imperialism.

Rahman is part of Political Asylum, a political comedy outfit formed in 2009 by Courteney Hocking and Mathew Kenneally, which often tackles systemic injustice:

Rod Quantock, featured here with his blackboard, deals in systemic satire. He has called for a ‘united front’ amongst comedians for progressive causes, and his 2009 stand-up show Bugger the Polar Bears, This is Serious roused people to climate action. Meanwhile, Political Asylum’s Stella Young’s recent Melbourne Comedy Festival show, Tales from the Crip, highlighted how people with disabilities are patronised and marginalised. In her roles as comedian, author and public speaker, Nelly Thomas — also part of the same troupe — has spent years shedding light on the politics of women’s health.

Clearly systemic satire does exist here in Oz. The real challenge is to popularise it. In the face of conservative attacks on women, workers, Indigenous Australians, refugees, independent media and our environment, this would be one potent way to fuel community anger and desire for genuine change.

Heck, we could even create alternative visions of our own.

–

Liam McLoughlin is a Sydney based writer and editor of Situation Theatre, a space for satirical and feature articles concerned with social and environmental justice.