Usually when you whack your skull, all you get for it is a painful lump you force your friends to touch. But for an incredibly rare few, a knock to their noodle fundamentally altered the very design of their brains – and in a way that revolutionised their lives. These otherwise ordinary people are known as ‘Accidental Savants’ – men and women who have unintentionally acquired a new capacity completely foreign to them beforehand. While most love their newfound abilities, such a dramatic change to their lives didn’t always come easily. To hear about the highs and lows of the condition, I chatted to a few folk with Acquired Savant Syndrome.

JASON PADGETT

Before accident: Futon salesman.

After accident: Number theorist.

One night in Alaska years ago, I was attacked while leaving a karaoke bar with my friend. I never really saw it coming – they struck me from behind, just with a fist. I remember so clearly the deep, sickening thud of it. Before I knew it, I was on my knees.

They punched and kicked me for what only must have been a few minutes. I thought I was going to die, which is a horrible feeling. I cried out for help, but everyone was frozen. Eventually, one of attackers asked for my ‘goddamn jacket’ – which they swiped and ran away.

By the time I was at hospital – even in the ambulance over – I could already tell things had begun to look different. Everything seemed a bit funky. I was on a lot of pain medication though, so I assumed it was just because of that. But the next day, things still looked the same.

Looking around, I saw that the motion of objects wasn’t smooth anymore – instead, it was jarring. It’s like one frame followed by another, like a television being paused repetitively. But between the movements of each object, I can see this visual trail in real-time between where an object was, and where it’s moved.

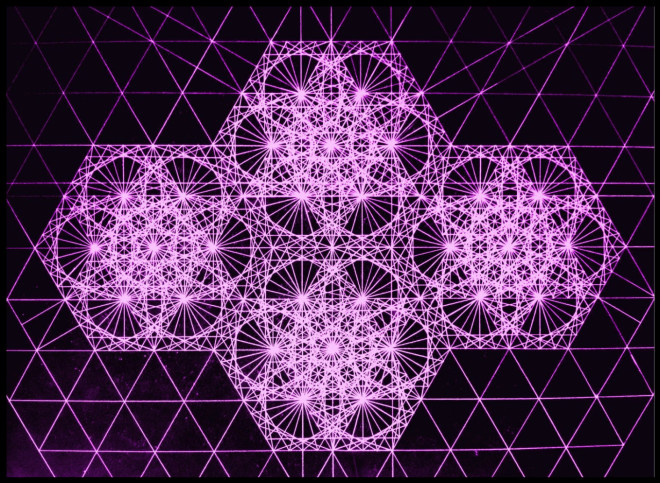

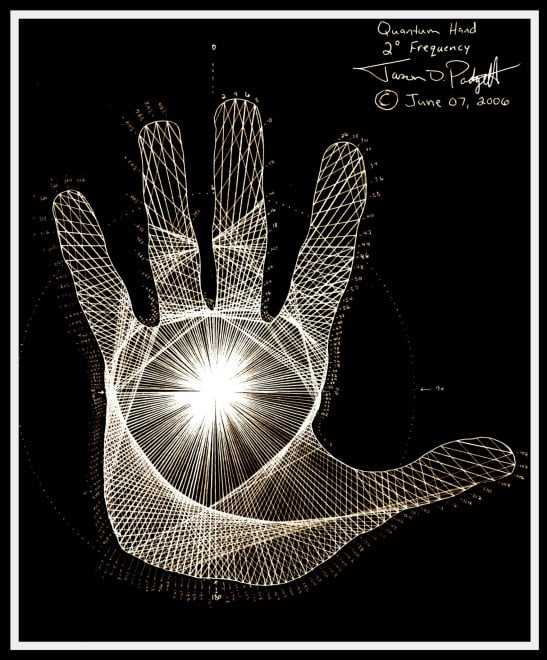

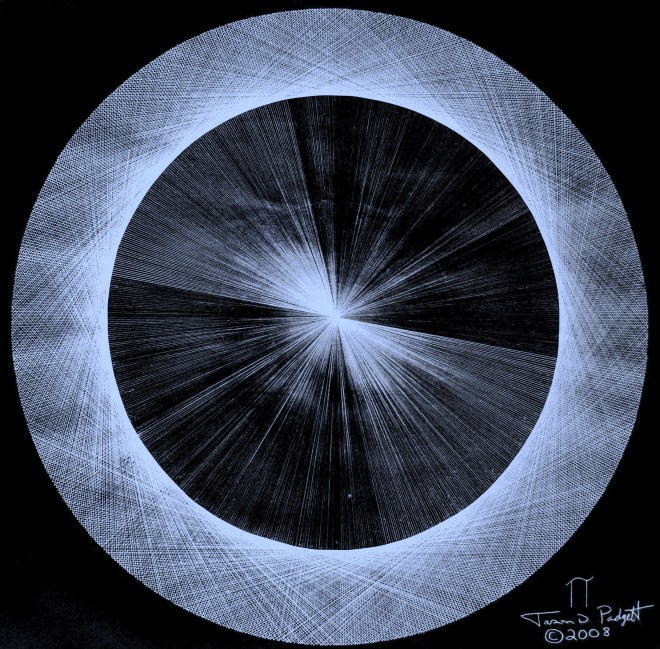

That little trail tells me all sorts of cool stuff, like how fast an object is moving and its velocity. The faster something is, the further apart an object’s frames are. Seeing like this makes you hyper-aware of the geometry of things. I started to see the mathematics designs in everyday things, like the fractal patterns of tree branches. I started drawing what I saw all the time, gradually realising that what I was seeing and the mathematics that described it were one of the same thing.

Images by Jason Padgett, including an illustration of Pi constructed of myriad overlapping triangles, a ‘quantum snowflake’ and a representation of how he perceives his hand moving through space-time. Purchasable here.

Take calculus-based physics for example — what the mathematics is saying is ‘let this shape equal this dot on a graph’. This dot is then going to change position on the graph, and we use mathematics to describe its movement. What I see is simply the natural form of mathematical equations.

I was never good at mathematics when I was a kid. I was one of those students who thought it was pointless, that it’d have no application. Now I study number theory and mathematics at university, and I even met a woman while studying who became my wife. We just had our first child.

But while I’m grateful for where my accident directed my life, there were definitely trade-offs. For a long time, how I saw was completely maddening. I just wanted it to stop at times. I didn’t want to see the way I did all the time, and thinking about it all constantly. There were times when I just wanted to rest.

I used to be so outgoing too, but after the accident I suffered severe post-traumatic stress disorder. For the first three years after the attack, I didn’t really leave my house. I put blankets up on the windows and became quite OCD. I became so aware of germs – I’d see every kid that wiped his nose, who then touched his mother’s hand, who would then try and shake my hand – I couldn’t help it; I’d see them everywhere. Eventually I saw a psychiatrist, who helped me a lot with feeling comfortable in the outside world again.

But my accident opened up this new way of understanding the world for me. And I have a family now, I mean I go back and let those thugs beat on me a million times just because of them. But there are times when I miss the moments of blissful ignorance. Visually, the way I see is wonderful. But you realise how much you need those moments to stay calm and rest. Life can be overwhelming otherwise.

TONY CICORIA

Before accident: Orthopedic surgeon.

After accident: Orthopedic surgeon who hears classical piano.

–

The lightning hit me at a family gathering in August 1994. I was using a payphone to call my mother, and halfway through talking to her the booth was struck. I remember seeing the bolt shoot out of the phone, striking me right in the face. I was blown out of the box by the force of it.

When I woke up, the pain was excruciating – even though I only suffered a small burn mark on my face and ankle where the lightning had travelled. Over the next few weeks my brain felt a little fuzzy, I had some trouble remembering names. But gradually things returned to normal.

Then, strangely, I began to feel an overwhelming desire to listen to piano. This was a total departure from my nature. I’d taken lessons as a kid but I hated it. I’ve always been a ’60s kid, my taste has always been rock n’ roll or nothing. But still, I travelled into the city and bought a CD of Vladimir Askhenzy playing Chopin. I listened to it every day for the next month.

But then I actually began to hear piano in my head. It was completely clear to me. It sounded like someone was playing a record in my head, repeated itself over and over. My mind was creating this composition, and it had a life of its own – all I could do was listen to it. I started penning down bits and pieces of it, but I eventually started taking piano lessons to properly understand it.

For seven months I worked with my piano teacher to transcribe the piano I heard. It was the same song every time, note-for-note – like someone downloaded it to my head. I was so absorbed by the music I was hearing — it sounded to me like something Mozart experienced, to hear beautiful music.

It took years of practice until I finally wrote the first composition that ever played in my mind. I named it “The Lightning Sonata”. But it wasn’t easy; it took up a lot of my life. It totally changed its direction.

The music became an absolute obsession. I would work my day-job as an orthopedic surgeon – but I’d be up at 4am and practice, and when I was home I’d be back at the piano again. I became a zealot for the music I heard. It seemed like it was the only reason I was alive.

It was a double-edged sword. It was rocky. My wife said that I had changed, and so did close people that knew me. I had subtle personality changes. It definitely was a rough time, I had lost sight of a lot of things. The music seemed more important to me than anything else. For a long time, I was out of balance. Eventually my wife and I got divorced and didn’t remarry for eight years.

The accident changed my priorities for what was important in my life. I remember at the time, that all I focused on was becoming a published academic as an orthopedic surgeon. I was trying to make progress in the literary field. But after the lightning strike, it suddenly didn’t seem important to me any more.

HEATHER THOMPSON

Before accident: Business strategist.

After accident: Painter.

–

Four years ago, I’d stopped on the way home at one of those warehouse supermarkets with my daughter. I was unloading shopping into the boot of my 4WD, when suddenly the hatch fell and caught the back of my skull.

It all happened very quickly. It didn’t knock me out, but I crumbled to my knees. My teeth snapped together so hard I thought I’d broken some for sure. My daughter began to cry in the trolley, so I pulled myself up and managed to buckle her up in the car.

I only lived five minutes away, so I decided I was OK and drove home. I walked through the door, passed my daughter to my husband, then collapsed in bed and slept for hours. When I woke up, I could tell my brain wasn’t functioning properly. I only went to the hospital when my sister told me over the phone that I sounded drunk.

At hospital, I passed certain motor-function tests, but failed basic cognitive ones. I couldn’t draw a clock – I’d draw one, think I did it right, but then my neurologist would look at me and say, “You have no idea what’s wrong with it, do you?”

Over the next few months, my condition only worsened. I became extremely sensitive to light and sounds, and I couldn’t even leave the house eventually. I couldn’t walk – I know I knew how to, but the whole world seemed tilted. Eventually I couldn’t even leave my room, where I stayed for four months.

I only began painting at the advice of a neighbour, who said it might help. I used my daughter’s paint kit, and tried to paint something. I remember it was fairly basic – but the colours seemed to jump right out at me. I felt like I had this deep understanding of them. It’s hard to put into words.

While it doesn’t seem that significant, painting completely changed the direction of my life. I never had an interest in art at all – I’ve always been a left-brained person. I didn’t even want to paint in high school. Before the accident, I was working as a nationally recognised entrepreneur and business strategist in the US. I was delivering keynote presentations all around the country. Whereas now, I have to paint all the time – it’s like my hands have a mind of their own.

I do consider my accident a blessing, painting helped my mind heal. But it’s still essential for my brain to function properly, because without a creative outlet I struggle to focus on things and my mind becomes exhausted.

For example, I’m studying a master degree in psychology at the moment, and in class I have to use colour to take notes. On one side of my page I’ll write the notes, and on the other I’ll capture the information in my own way in splashes of colour. It’s hard to believe, but they always seem to represent what I learn in each class.

DEREK AMATO

Before accident: Corporate trainer.

After accident: Musician.

–

Overall, the accident really changed my whole design. I used to operate a sports management company, and was a corporate trainer as well. I never played much music, I had a guitar but that was pretty much it.

I hit my head shortly before my fortieth birthday at a family reunion a few years ago. My friend had thrown a football over the pool, and I thought I’d jump to catch it. I knew I was diving into the shallow end, and planned to roll in on my shoulder. But that didn’t really work. I struck the bottom of the pool with the upper left side of my skull. The doctors diagnosed me with a massive concussion.

A few days later, I was at my friend’s apartment – and I noticed a small keyboard in the corner. I remember feeling drawn to it as we were talking. Eventually I walked over and started having a bit of a play. Then, I remember just going crazy. I’d never played before, but it was completely fluid to me. My hands had a mind of their own. Now it’s like there was this rolling script with music, one my mind makes without me even having to think about it.

My accident unlocked this dormant part of my brain. It was a gift, but there were obviously downsides too. The accident badly impaired my memory. I have gaps where I can’t really remember parts of my life. It also affected my short-term memory. If we’re having a conversation, and someone tells me their name while I’m doing something – its guaranteed I’ll ask you your name a few minutes later.

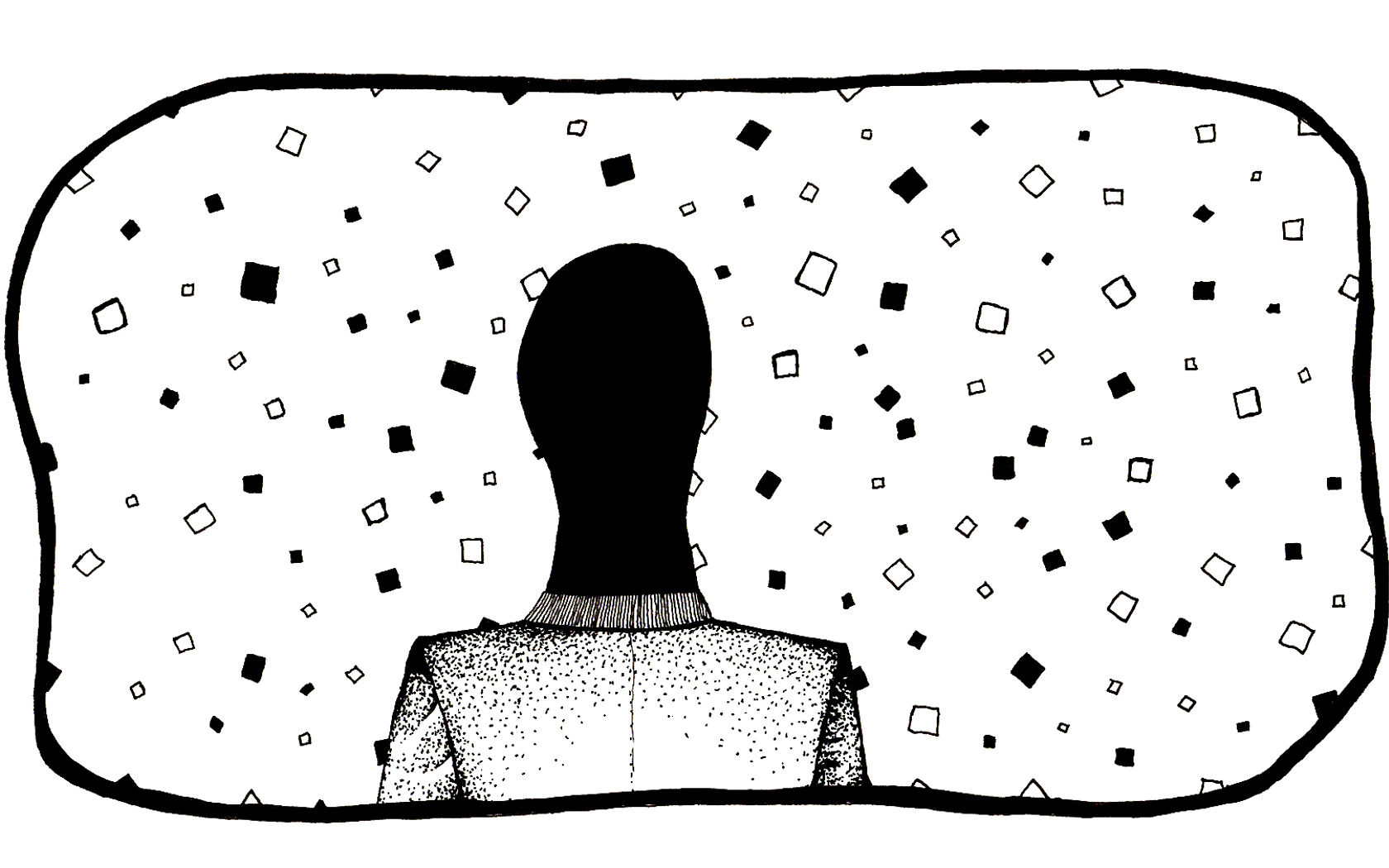

I also always see these black and white squares now as well. Doctors think they’re visual representations of many notes layered upon one another – each one for a different instrument. One might be for violin, one for cello. They must be guiding my fingers where to go. It’s like my mind is creating music at a speed that my hands can’t keep up with.

The accident really changed the person I am, and it hasn’t always been positive. I’ve become hypersensitive to sound and light now too. I can’t be around fluorescent globes because they make me feel really sick. And I also lost around 35% of my hearing in my left ear because of the accident.

But I’m a more intuitive person now, and more empathetic than I ever was before. It made me a much more loving person.

–

Jack Callil is a male human, freelance writer, and illustrator living in Melbourne. You can follow him at @Jack_Callil.