How Australia’s Foster Care System Is Forcing Teenagers Into Homelessness

The US, UK, New Zealand and Canada have all extended the foster care age to 21. Why hasn't Australia figured it out?

Across Australia on any given night, an MCG’s worth of people will experience the cruelty of homelessness. That’s close to 120,000 with nowhere to call home; sleeping rough on the streets, in boarding houses, couchsurfing, or packed into severely overcrowded dwellings.

Homelessness is terrifying no matter what walk of life or age you experience it. But it’s especially alarming to think that one of the largest growing groups without a roof over their head are young Australians under the age of 25, with those from Indigenous, migrant, and queer communities being most over-represented.

Contrast that growth with another increase seen nationally — the most recent HILDA survey found that 80 percent of Australians aged 18 to 21 are still living at home with their parents or guardians. The same survey also revealed that earnings inequality has increased, as has the shift from full time to part time and casual work, with underemployment surging among young people.

Meanwhile, the 2017 Rental Affordability Snapshot found that out of 67,000 properties surveyed, less than 1 percent were affordable for those on Centerlink benefits or earning the minimum wage.

Priced out of affordable housing and secure employment, those who nonetheless retain stable housing with their family usually have greater outcomes in higher education, the job market, and the development of strong support and social networks.

But what about those who don’t?

What Were You Doing On Your 18th Birthday?

Turning 18 is the milestone so many teenagers look forward to. It opens the door to your first car, ushers you into the voting booth, and proudly declares you ‘an adult’. For many, that special year is all about celebrating final VCE exams, roast and toasts at your 18th birthday party, or taking a gap year to figure out your next steps.

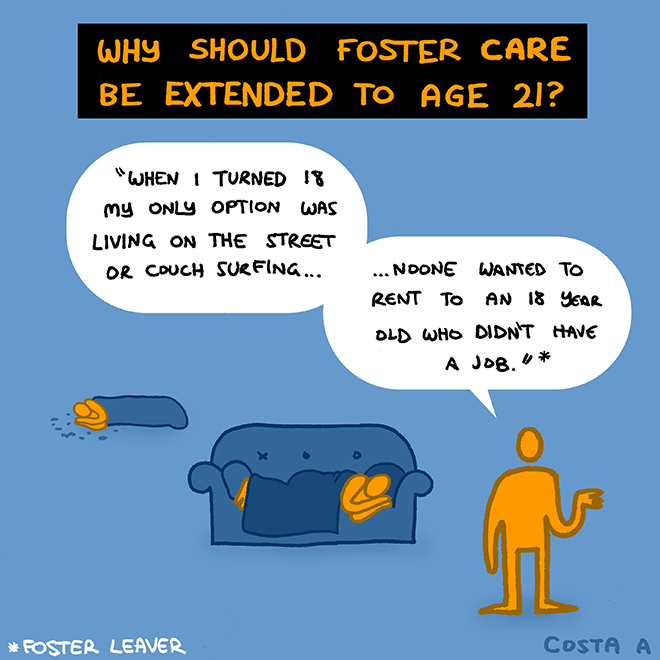

For Dan, turning 18 meant waking up in a public toilet where he was sleeping rough after he was cut off from his foster care family.

“They didn’t want to get rid of me. But they just couldn’t afford to have me around anymore because they weren’t getting any financial support from the government when I turned 18,” he said. “It was so bloody hard saying goodbye to them. It was the first time in my life I felt like someone gave a shit about me.”

The advice he was given was to find a bed in adult homeless shelter; Dan said he felt safer in the public toilet than he did after one night there. “I was still a kid and I was surrounded by people double and triple my age with a lot of issues. I had nowhere else to turn after I slept on my mate’s couches and floors for months.”

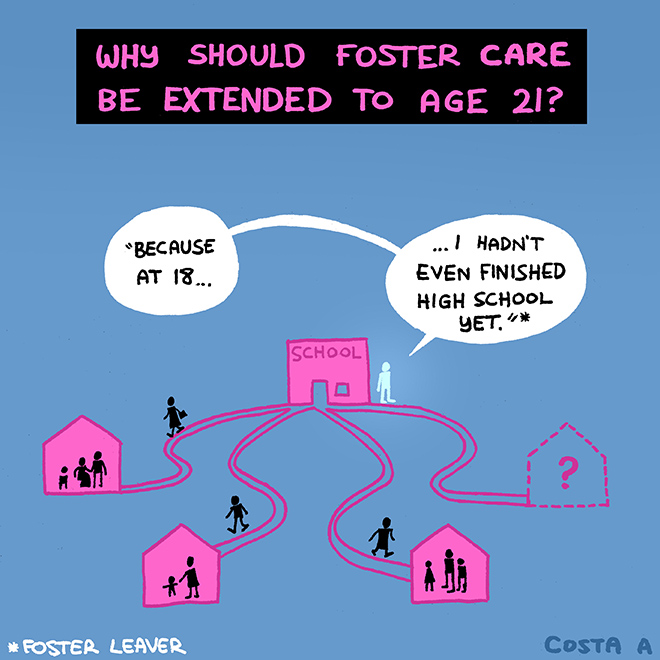

The causes of youth homelessness are as complex as they are tragic. But as Dan puts it, “What landlord would want to give over the keys to their house to a 18-year-old with no rental record, no permanent job, not even a VCE certificate?”.

Youth Homelessness Matters

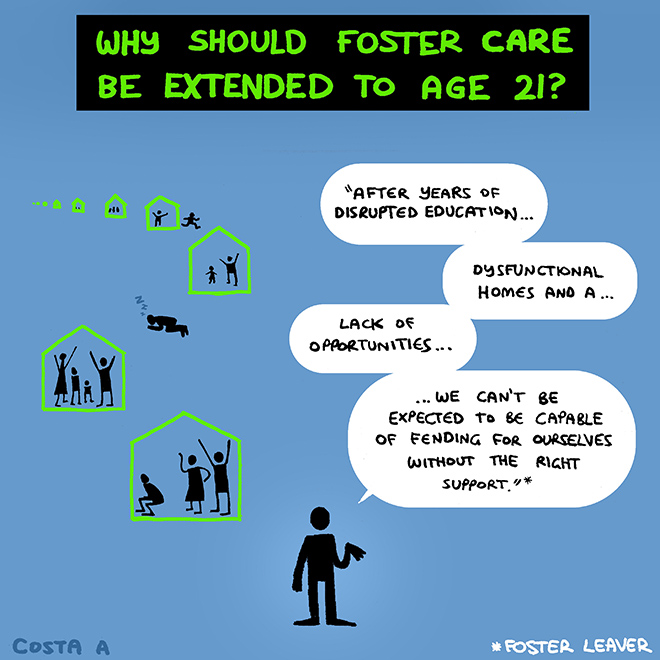

The latest Swinburne University national study of homeless young people found that 63 percent had recently been evicted from foster care. In Victoria, and many other states across Australia, we cut off foster kids before their 18th birthdays. For most, that means there’s no more case workers. No family support. Nothing.

Within one year of being evicted from their foster care placement, most young people will experience homelessness, be unemployed, become teenage parents or have contact with the youth justice system.

Against the many causes of youth homelessness, one solution stands out as a simple, effective and proven to help vulnerable young people avoid poor life outcomes. The United States, United Kingdom, New Zealand and Canada, rather than cutting foster care off at 18 years, have extended it to an optional 21 years. Why? The evidence is overwhelming, extending care works.

The remarkable success and improved life outcomes for young people when the age of foster care is extended provides a viable model for Victoria and other states to emulate. It’s what works in the best interest of the young people, their communities, and society at large.

Where this reform has been implemented, it’s halved youth homelessness from 39 percent to 19.5 percent and doubled education engagement for these young people.

It’s also seen a decrease in intergenerational disadvantage, hospitalisations down from 29.2 percent to 19.2 percent, arrests dropped from 16.3 percent to 10.4 percent, as well as alcohol and drug dependence reduced from 15.8 percent to 2.5 percent.

It’s not just the evidence that speaks volumes for this reform, it’s also the young people who’ve been through the system.

Casey was in foster care from the time she was 12. She’s 24 now and believes extending care to 21 would’ve helped her establish her life.

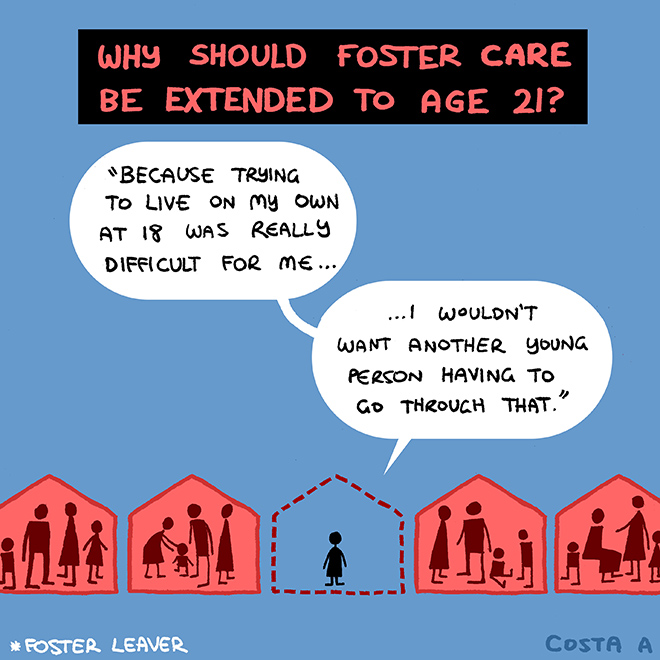

“When I left my foster home before I turned 18, I found it impossible to budget my dole money. Looking back, it was way too much for me to handle because I already had such a difficult childhood and made so many mistakes. It was so stressful for me that I dropped out of school. I just wish I had the a couple more years to get my life together.”

Adolescence Is Priceless, But Money Talks

As well as failing the young people who experience it, youth homelessness is a drain on the state and federal governments that don’t invest in early intervention initiatives and reforms to stop the flow of young people becoming homeless in the first place.

“For every young person who becomes homeless there is an average expenditure of almost $15,000 per person per year on health and criminal justice services,” says lead researcher Associate Professor David Mackenzie.

Co-Chair of Home Stretch and CEO of the Centre For Excellence In Child & Family Welfare Deb Tsborbaris believes society can’t put a price tag on a young person’s future. “It’s time we recognise the worth of young people in the care system and ensure they have the support and encouragement they need to pursue a happy and fulfilling life.”

Deb recognised that some states, such as Victoria, fund a range of ‘leaving care’ or post-care support programs but believes that, “They are discretionary and insufficient for young people who have been evicted from their care placement, especially if they’ve had childhoods marked by instability and trauma.”

Donna Stolzenberg is the Founder and Director of Melbourne Period Project, a charity that provides essential living items, support, and menstruation items to women, non-binary folks, and trans men experiencing homelessness. Through her work, she’s seen a drastic rise in young people sleeping rough needing their services. But more than menstruation items, it’s more often the support they require the most.

“When I ask young kids living on the streets the one thing that could’ve saved them from this life the answer is always the same: ‘A family.’ Someone to mentor them into their adult years and teach them what it means to be a happy, functioning adult”, she said.

Donna has also been a foster mother for many years and understands the importance of providing those extra few years of care.

“I’ve housed 17-year-olds who couldn’t make a bed or a Vegemite sandwich. How can we expect them to be ready for the responsibilities of working full-time, securing and managing a 12 month rental lease, and paying their bills? We have to remember with these children that there isn’t any family to turn to if something goes wrong. There never was.”

The Times Are Thankfully Changing

While young people continue to be overrepresented in Australia’s homelessness statistics, some positive change is being seen in parts of the country, with both the Tasmanian and South Australia governments legislating and funding the extension of foster care to age 21.

With sustainable evidence showing this will lead to a decrease in youth homelessness, child welfare organisations, peak bodies and advocates are calling on the rest of the nation to follow the positive example set by the two states.

Foster care leaver Dan also supports the extension of care to age 21. “It’ll save other foster kids going through the same skewed up experiences I did,” he says.

“For that reason alone, it’s worth fighting for.”

—

Nevena Spirovska is the Campaign Manager for Home Stretch — an organisation calling on the age of foster care to be extended from 18 to 21.