Yael Stone: Are Stories Important? Or Do The Wankers Who Make Them Just Want To Keep Their Jobs?

Yael Stone asks: Do stories matter, or are we all just wankers?

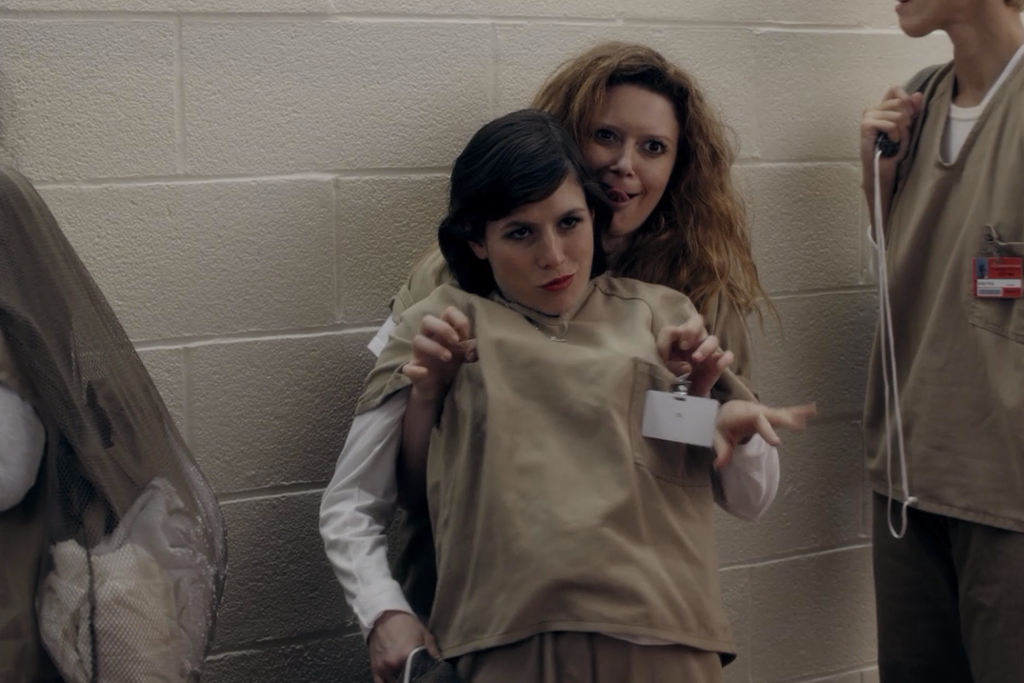

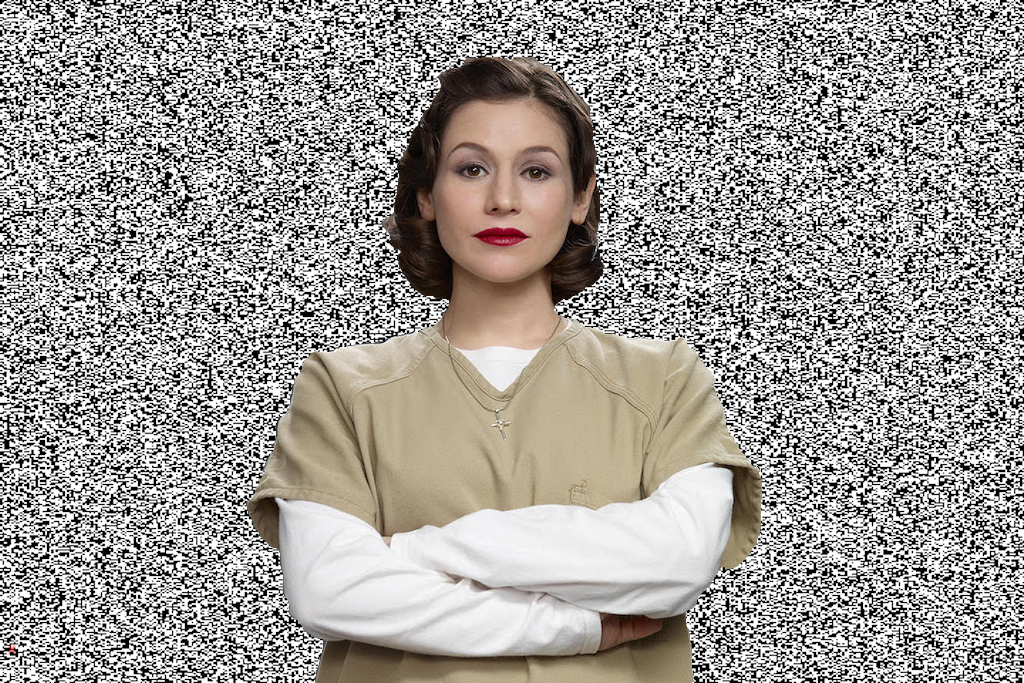

The following is the keynote speech, Streaming Is The New Black, delivered by Orange Is The New Black star Yael Stone at Video Junkee on Friday, July 28.

–

“When you are in bed with your laptop, eating your cereal and quietly singing, ‘The animals, the animals…’ Don’t be fooled. This is nothing new. Stories existed long before streaming and are at the very heart of our humanity.

I wonder at the first story ever told, a birth, a death, a triumph or humiliation? Fact or fiction, a misremembered moment that illuminated something bigger. But we can’t remember the story of the the first story because we have never been without them. Perhaps their beginning is in perfect step with the dawn of the conscious mind?

Somewhere between 50 and 100,000 years go something happened to humans beings. We started make art, which to my mind means we started to ask, why are we here and what is the point? We don’t have story fossils, per se, but I imagine that as the Jawoyn people in Arnhem Land painted mega fauna that existed 60,000 years ago it was accompanied by Dreaming stories. 20,000 years ago in the Pyrenees I feel sure the sounds of stories were echoing from the Lascaux Caves while the horses and deer were painted dancing across the ceiling. Stories do the same thing that the hand outlines blown on to the walls of the Sulawesi cave do; they say “we are here, we exist”.

In Ancient Greece being an audience member at the City Dionysius festival was not a passive act. It was not ‘Mum’s got a subscription to the theatre and her friend got gastro so I guess I could go along with her, maaaaaybe.’ No. Being one of the thousands of people that packed into the amphitheater each day of the festival meant you were a part of the society. Up there with voting, engaging with the narratives of the festival was essential. (Just because I just said the words ‘Ancient Greece’ please don’t let yourself glaze over with high school history disassociation!) Think about how the idea of a passionate and thumping audience connection might still talk through time.

“I’m one of a long line of wankers who will, sometimes through tears, decry the power of the story as essential.”

The obsessive fan messages I get from people engaging with Orange help me understand how people’s sense of morality is teased out from watching the gods and monsters of Litchfield. The fan fiction, the memes, the investment in character and plot. Is it possible that stories are just as important now as they were in the 5th century BC? I might say yes, but I’m an actor, why would you believe me? I’m one of them.

I’m one of a long line of wankers who will, sometimes through tears, decry the power of the story as essential. Its absolute necessity in maintaining a functional and healthy society. But I have to wonder, there’s a hell of a lot of stories flying around, digital reams of ‘content’, and yet it would be generous to say to say this society is functional, and a joke to describe it as healthy. So I have to ask myself, are stories as important as the story makers tell us? Or do they just want to make money and keep their jobs?

Make no mistake people are making money from stories. Over many thousands of years our instinct for story has become an industry. An incredibly complicated, sophisticated and at times conflicted industry where money, politics and hidden agendas mean that parasitic media brain zombies might eat our faces at any moment and we just can’t get enough of it .

My guess is shit got complicated the exact moment humans realised that they could use stories to manipulate people and sell things. What a devastating surprise, right? But does that mean every story made is corrupted by the bottom line? Examining the commodification of streaming stories means we might need to look back to a time when slap bands and yo-ho diablos were peaking.

The early internet was a cute moment where for a brief window we regained a kind of age of innocence. There was a story telling space without ads and people shared stories without the particular aim of likes or follows. In our family the early internet meant sitting for hours listening to an excruciating and unending dial up wail that was a portal to more dial up wailing. But apparently other people were using it to share human stuff and in a whole new un-patrolled medium where we could once again declare, “We are here. We exist.”

Then the market did as it is wont to do, it capitalised. In 2006 Google bought YouTube for more money than we can really conceptualise. And it wasn’t just so they could get across which “Oh Hai” cat was the cutsiest. No, 10 months after the purchase Youtube started to advertise. They had that hungry market pegged, the ferocity with which we wanted it, meant we didn’t just watch, we consumed. I figure its around this time that we start to refer to internet stories as ‘content’. It’s strange to the call the thing that people want ‘content’. By definition it means the things that are held or included in something. So if the story you actively searched for isn’t the ‘something’, but rather a part of the something, what’s the rest? If the story is being held, what is doing the holding?

I’m going out on a limb and to suggest that the other parts are the platform that you (or your friend from whom you stole the password) might pay for, or the advertising that gently cradles your watching. The name content perhaps borrows its name from content marketing? Which basically snuggles promotion in with stuff you like. Content is the spoon full of sugar helps the medicine go down. Good stuff to be aware of if you have any intention of being a conscious consumer. The way we talk about stories is coded by the overwhelming forces of our times. In our history some stories have been coded with religion, others with war, I think our most popular storytelling mode of the time, streaming, has been coded by the market, which is why we ‘consume’ our ‘content’.

So, is this a problem? Is the power of stories we tell corrupted by the money that got them made, therefore leaving them void? I’d rather not throw the baby out with the gold plated bath water. The Medici family funded the art of the late Renaissance, we might not have Mozart without Baron Gottfried Van Swieten and perhaps there would be no Golden Age of video and streaming without the commodification of internet storytelling.

It’s that big streaming money that funds the incredibly incisive shows with amazing production values that we’ve come to demand. It’s the draw power of those stories that makes the money, which incentivises making good stories or at least popular ones. Which may mean the bread gets buttered on both sides for those that consume and create. For the time being we seem to be making merry, around the candy-stripped may pole of money and popular entertainment. Longtime bedfellows with serious co-dependency issues.

I was given an unlikely front row seat to the birth of the bedfellow’s streaming baby in 2012. I’d left Australia to try to live in New York as an actor. (For the record as foolish and giddy as it sounds.) Four months later I got a job on a show called Orange Is The New Black made by a company called Netflix.

Netflix, which used to engage in the quaint cottage industry of mailing people actual physical DVDs to their homes, was about to explode the game by making its own original content, completely bypassing TV and going directly to the spaghetti string magic that is the internet.

At the time people looked at me with pity as I tried to explain my new job. “It’s not a web series (I don’t think) but not a TV show either in the traditional sense. It lives on the internet but its not of the internet.”

I think most people thought I was doing porn.

Being part of that first Netflix explosion was completely surreal. We seem to herald a new phenomenon in terms of how people interacted with stories, remember this was a moment when ‘Binge Watching’ was kind of a hip new term. It was also a huge moment for the kinds of stories we were telling, how we could tell them and who we could tell them to.

Netflix gave Jenji Kohan, our prophetic genius show runner a good deal of rope to make the show she wanted to make. For me that meant this small, white, secular Jew, from Australia was part of a show exploring the heartbreaking complexity of incarceration in the USA and finally acknowledging and celebrating the existence of multifaceted Black, Brown, Latina, Trans, Gay, Bi, Big, Small, Older, Wilder, Weirder, Misunderstood women who make up reality. Just the fact that women out numbered men on the call sheet was enough to blow people’s minds.

Turns out people want to see something closer to themselves on their screens.

Does that answer the question, does representation alone mean that stories are important and have impact? Overriding or even justifying the complicating dollars that bring these stories into existence? Mounting instances where change has been made possible by the door wedged open by stories lead me to a yes.

Laverne Cox grew up in Mobile, Alabama, an African American Trans woman. A talented dancer, an actor, a performer with huge dreams and absolutely no roadmap for how to get there. Trans people of colour have some extreme obstacles to overcome in this society let alone in cracking Hollywood. Their staggering over representation in the homicide and unemployment rate is a small window into the realities of what that experience can be. I can’t imagine what it was like for Laverne to keep walking into audition rooms that didn’t have a place for her. Not the kind of roles she was looking for. But she was committed to finding that job, and she did.

When Sian Hedder and her team wrote Sophia Bursset’s backstory they made room for Trans representation. When Laverne knocked it out of the park she made it seem ridiculous that it had ever been any other way. And then she was nominated for an Emmy. And then she was on the cover of Time; the tagline read “The transgender tipping point, America’s next civil rights frontier”.

And then they threw every award available at her. As of last month June 22nd is now Laverne Cox Day in New York City. Oh, and she was just nominated for another Emmy. All of a sudden trans and cis people have a new hero who’s proving the impossible is possible. Second to that, people who don’t have a trans person in their lives or those that feel judgements about trans lives suddenly have a human face and soul that breakes down the distance that a label can afford.

Perhaps for some, it’s still really challenging and that’s workable because challenge is a place fertile for change. Most important of all, trans kids get handed a brand new map, the bottom right hand corner is stamped LC #transisbeautiful.

Recently I heard Joe Biden speak and he said that the culture always moves a good deal faster than government. I imagined culture racing ahead and reaching back to grab government’s hand, dragging it along kicking and screaming. And I only have to think about the state of marriage equality here to know how serious the lag can be. To this riptide effect of culture on government I point to Eric Holder’s statement just a year after OITNB was released, he was the Attorney General at the time and he said this;

“Clearly, criminal justice reform is an idea whose time has come. And thanks to a robust and growing national consensus – a consensus driven not by political ideology, but by the promising work that’s underway – we are bringing about a paradigm shift, and witnessing a historic sea change.”

Now of course I’m not saying that work he referenced was OITNB, certainly not. But I do think we changed the conversation and we humanised people who are systematically de-humanised, playing an important role in that growing national consensus.

Much closer to home I can attest the show also affected me on a personal level which has meant I proudly serve on the board of Liberation Prison Yoga and teach weekly at the women’s jail on Rikers Island. For whatever small difference it makes I know definitively storytelling brought it about.

Another larger scale impact I’ve witnessed is the audience response to the death of Poussey, played so beautifully by Samira Wiley at the hands of a Corrections Officer exerting inappropriate force. A tragedy seen time and time again in the real world, Jenji was once again reflecting our reality back at us. The fans went crazy, heartbroken at losing a fictional character they’d come to know and love.

Empathy can come from unexpected places. People who where dissociated from the Black Lives Matter movement on a personal level suddenly had a gateway into the movement. Danielle Brooks, who is so brilliant as Taystee, sagely harnessed the moment and sent a powerful message, “Every time you think of Poussey, think of a real human being. Shed a real tear. Get angry about a real death.”

In 2016 I was lucky enough to be part of a SBS/Blackfella Films series called Deep Water. The story is told in current day Sydney but it was set against the context of real hate crimes that specifically targeted gay men. There are potentially 80 unsolved murders in Sydney from the late 70’s to the late 90’s fitting the category of gay hate crime. I spent most of my life living in Sydney and had no idea about these horrific attacks. Outside of the investigative journalism of Rick Feneley, this ugly history was largely unknown to most Sydneysiders.

Storytelling gave us a chance to talk about this open secret and the creative license meant we could stay away from the sensitive specifics that were recently the subject of a State Coroner’s inquest. I want to hope that Deep Water allowed victims and the families of victims to feel acknowledged, but perhaps that’s naïve. At the very least we were able to bring shame like this into the light, people should know what happens in their backyard.

Stories can do that.

Looking at 2017, there are some great examples of story telling beating right in time with the pulsating gash that is public discourse, and hopefully helping some people feel and think.

In the US a woman’s right over her own body has been under political attack for some time. Trump’s health bill is whole new level of aggression and would see Planned Parenthood defunded. Planned Parenthood provides care including STD/STI testing, cancer screening and prevention, contraception and abortion services for those who can’t afford to go to a family doctor, which is extremely expensive if you don’t have insurance. In May the NSW Parliament voted no on a bill to decriminalise abortion. Which means doctors have to continue to use legal loop hole to approve an abortion, outside of that a patient could face 10 years in prison. Not a single person in the NSW government voted yes, preferring to maintain an archaic 100-year-old law that leaves women in a precarious place.

People, particularly women, are angry and fearful about this rising political climate. In January 2017 people in all seven continents — 3.3 million in the US — participated in the Women’s March. As if birthed by the zeitgeist, the series The Handmaid’s Tale, adapted from Margret Atwood’s novel, arrived with all the terrifying suffocation of a dystopian reproductive prison.

Popular culture lets out a cry, people have the opportunity for a visceral, cathartic experience and the chance to fuel their feminism. Supporters of Planned Parenthood have turned up in the Handmaiden’s red robes in public protest, defending women’s rights.

Storytelling bleeds into real life and it seems clear that culture and politics are dancing, one beckoning the other, baiting and informing, becoming translator and the camera obscure, mirror up to nature. That worries some people. Donald Trump asked “When does ‘art’ become political speech?”, after a recent production of Julius Cesar was criticised for its “Trump stabbing” take on this inherently political play.

I think the answer is that all art has political, social, cultural bias. We make and consume stories to understand ourselves, try to understand other people and situations and seek confirmation and validation in a very confusing world. Unless your art has been made by a robot, which does happen, a human, with filthy predilections and luminescent brilliance made it, and is likely to have left traces of themselves all over it.

Art is the very best and worst of us.

So what’s for the future? I bet there are a few ideas in this room. With outlets like Foxtel taking more risk than ever in Australia with shows like Wentworth and Picnic At Hanging Rock those ideas may well find a happy home.

In the name of sharing, I’ll go first. I’d like to produce a show that’s a just-around-the-corner imagining of our world that opens with the sunrise on the first earth day after the two degree climate increase. Marking the official failure of the Paris Agreement. It would be a recognisable but strangely altered Earth. The changes ominous and yet tangible in their domesticity. We’d track the humanity of adjustment, those who give up, those who are reinvented and given this morbid opportunity are able find new meaning. In an ideal world the first episode is written by George Saunders and Lally Katz. I want to make a story that brings people imaginatively into a place where we can engage with climate change beyond the paralysing facts and projections.

Of course, as one on the ‘story heals all’ wankers I wonder if the imagination is the way to unlock engagement and action?

Do I think that stories are the be-all-and-end-all of social political impact? No, of course not. We have to act to create real change. But I do believe a story can shift a pebble, that might send an echo, that could cause a landslide that ultimately changes the face of the mountain.

If we’re consuming, our job is to be smart and decode. Consume but don’t be consumed. Be aware of who, what, where, why and how the stories we are watching came into being. Treat all streaming platforms as your own personal City Dionysus Festival. Become curatorial, be analytical about what your diet is. Make no mistake, the cultural stimulus feed ourselves is changing our brains and our society. You are what you eat is not just about food. If you’re making content you might want to consider why and to what end. If it’s because it’s fun and you want to entertain people there’s real merit in that. If it’s because you want to capture people hearts and open new perspectives I truly believe that story has that power.

We need to be brave, whatever kind of story telling we do. The closed doors of institutionalised storytelling feel impossible, like we don’t even know who the gate keepers are let alone how to get passed them. But have faith, these days the most obvious route is rarely the one to get you where you’re going.

I was going to reel off a bunch of unlikely storytelling heroes but maybe its better you cast yourself as the unlikely hero?

If the path doesn’t exist for you yet then I’m excited to see you beat in down.

I want to hear from you.

–

Read our full interview with Yael Stone here, or check out more from Video Junkee here.

–

Yael Stone is an award-winning actor who has worked extensively in Australian film, television and theatre. She also plays Lorna Morello in the Netflix Original series Orange Is The New Black.