Why You Should Get To Know The Strange, Beautiful Art Of Chuck Close

"Inspiration is for amateurs. Show up and get to work."

When I first visited San Francisco’s Museum of Modern Art back in 2011, I was given the option at the front desk to pay a little extra to see the touring exhibition, The Steins Collect. The immense collection, put together by the Stein family (Gertrude and her brothers), was heavy on classics: Matisse, Picasso, Paul Cézanne, Pierre-Auguste Renoir and others. It was also jammed; tickets were timed to allow small waves of people in every few minutes, like one of those traffic lights at a freeway entrance, and you could barely move for people weeping over the Renoirs.

I was struck by the works’ obvious beauty, but also how oddly unmoved I felt by them. Having seen footage of people crying in front of certain masterpieces, I briefly wondered if I was missing a gene when it came to appreciating the 20th century masters, though I knew the answer to that question lay somewhere downstairs, away from the sobbing Stein-collection-crazy crowds, and amid the collection of postwar American art: my tears were saved for Chuck Close’s portraits.

Photorealism, or hyperrealism or super-realism depending on who you ask, was my jam as an art student at school. I vividly remember, on the day of my final Year 12 art exam, suddenly deciding – despite having devoted most of my swotvac study to Dada – to write my personal essay about photorealism, with Close a major feature of the piece. Let’s just say the last-minute decision didn’t quite set my ENTER score alight, but my love of photorealism remained.

And it was Close’s early work, firmly within the photorealist realm, that first caught my eye. Working from photographs, Close painted huge, intensely realistic portraits, both of friends as well as self-portraits. Big Self-Portrait (1967-68) has been described as a watershed moment for Close, artistically, as he began to move away from mere photorealism – to wit, paintings that “look like photos” – and towards his trademark uncompromising form of portraiture, inspired partially by a desire to debunk the critic Clement Greenberg’s notion that portraiture was beneath “advanced” artists.

–

Picking apart a picture: using art to memorise faces

The intensely detailed, almost analytical quality of his work is made all the more remarkable by the fact that Close suffers from prosopagnosia – more commonly referred to as “face blindness” – and finds it difficult to recognise faces and recall the features of those he has met.

“My art has been greatly influenced by having a brain that sees, thinks, and accesses information very differently from other people’s,” he told Lisa Yuskavage of Bomb Magazine in a free-wheeling 1995 interview. “I was not conscious of making a decision to paint portraits because I have difficulty recognising faces. That occurred to me 20 years after the fact when I looked at why I was still painting portraits, why that still had urgency for me. I began to realise that it has sustained me for so long because I have difficulty in recognising faces.

“But I can remember things that are flat, which is why I use photography as the source for the paintings. With photography, I can memorise a face. Painting is the perfect medium and photography is the perfect source, because they have already translated three dimensions into something flat. I can just affect the translation.”

“Affecting the translation” is a handy way to describe Close’s artistic evolution. He works incrementally, translating the photograph to the canvas in grid form; initially this was just a tool of the trade, an alternative to projecting or tracing onto the canvas, but eventually influenced his actual technique.

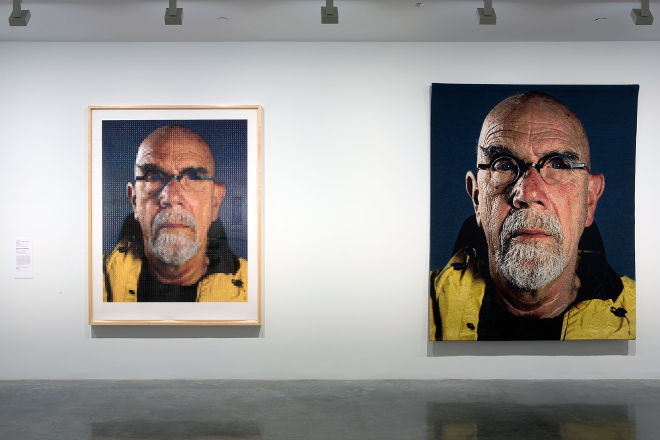

‘Traditional’ painting gave way to adventures in, variously; Mezzotint, a painterly imitation of the three-colour process (during which he would wear cellophane-covered glasses so as to focus solely on the one colour); fingerpainting; and eventually, in the late-’90s, an abstracted, low-resolution “grid” technique whereby the portrait is visible from a distance, only to shatter into hundreds of individual, abstract ‘segments’, each a tiny painting within itself.

–

“Inspiration is for amateurs. Show up and get to work.”

Part of this artistic evolution was a practical fact: in 1988, Close suffered a spinal artery collapse, which left him paralysed from the neck down. Through rehabilitation and therapy, he was able to regain some movement in his arms, but he has relied on a wheelchair ever since. The abstraction of his work after what he calls “The Event” was due in part to his reduced range of motion, as he would now paint with a brush taped to his wrist, aided by an assistant where necessary.

It was one of the latter that was the cause of my SFMoMA tears – not for any ”inspirational” reason, despite Close’s conquering of what could have been, for any other artist, a career-ending incident, but because of the sheer beauty of the work. He has since employed jacquard tapestry, and even provided immense Polaroid portraits for Vanity Fair’s 2014 Hollywood Issue (with all their pores and wrinkles on show, I wonder whether the actors and directors involved missed the flattering ethereal quality of Annie Leibovitz’s theatrical portraiture), but it’s the fragmented ‘90s portraits that I return to.

Is this because, as a child of the very early Internet, they remind me of spending fifteen minutes downloading an appallingly low-res JPEG of a matinee idol on lazy afternoons in 1997, then printing it out and using an entire cartridge of ink in the process? Possibly; and through all this I am also aware that there are plenty of uncharitable people who think that Close’s work from the ‘90s onward is “art by committee”, but you know what? I don’t care.

Most impressively, at least to someone with a near-psychotic work ethic, Close seems circumspect about whether or not he is – as we like to call noted artists – a genius, or someone plugged into an eternal wellspring of creative inspiration. For him, it’s work.

“Inspiration is for amateurs,” he said. “The rest of us just show up and get to work. And the belief that things will grow out of the activity itself and that you will — through work — bump into other possibilities and kick open other doors that you would never have dreamt of if you were just sitting around looking for a great ‘art idea.’ And the belief that process, in a sense, is liberating and that you don’t have to reinvent the wheel every day.

“Today, you know what you’ll do, you could be doing what you were doing yesterday, and tomorrow you are gonna do what you did today, and at least for a certain period of time you can just work. If you hang in there, you will get somewhere.”

As it turned out, not long after I cried in front of the Close portraits at SFMoMA, I had to rush back to my hotel to file a story. It’s nice to know now that Close himself would have supported that endeavour.

–

Brought to you in partnership with the MCA. All images taken at the ‘Chuck Close: Prints, Process and Collaboration’ exhibit, Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney, 2014, courtesy the artist and Pace Gallery, New York © Museum of Contemporary Art. Photographs: Jess Maurer

–

Clem Bastow is an award-winning writer and critic with a focus on popular culture, gender politics, mental health, and weird internet humour. She has sat in each of the Back To The Future trilogy Deloreans, but can’t drive. She’s on Twitter at @clembastow.