George Pell’s Latest Defence Of The Church Is Wrong For All Sorts Of Reasons

The Catholic Church is not a "trucking company", George.

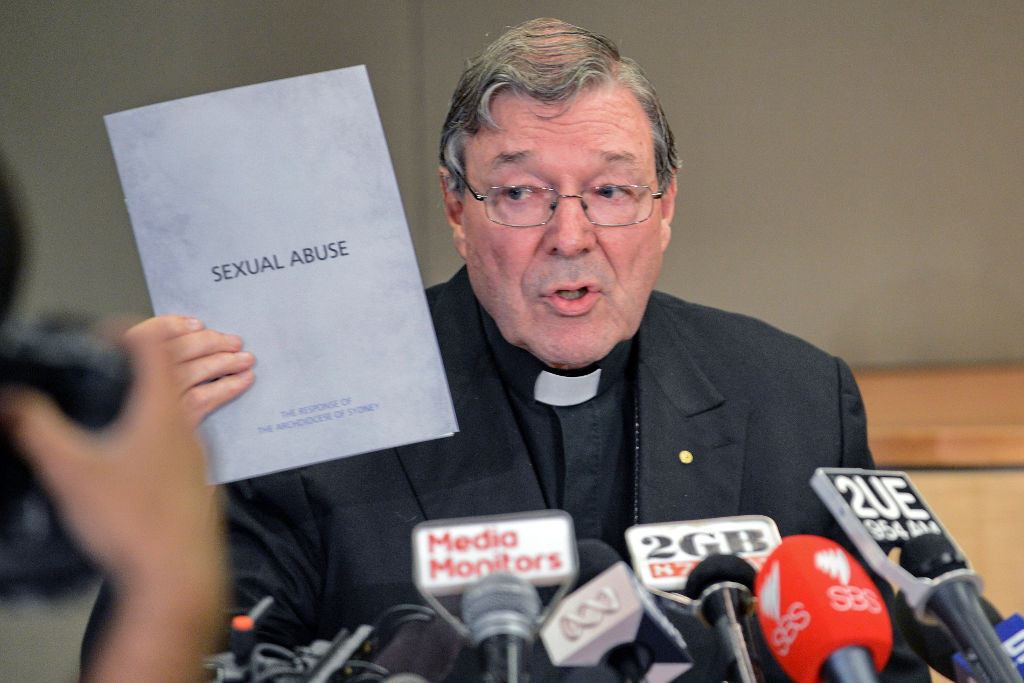

Cardinal George Pell is, by all accounts, a very intelligent man. Despite this, he seems to have no sense for what the political classes call ‘optics’, which is to say that how the public perceives him seems not to enter into his calculations. (Whether this is borne of ignorance or a lack of care remains an open question.)

The latest example of these bad optics – one of a long succession of examples – is his analogy, delivered last Thursday to the Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse, of the Catholic Church as a trucking company with a driver who happens to be a rapist. “If the truck driver picks up some lady and then molests her, I don’t think it’s appropriate, because it is contrary to the policy, for the ownership, the leadership of that company to be held responsible,” he told the commission via video link from Rome.

Now, strictly speaking, what Pell has said is true. Ignoring the issue of whether it’s appropriate to tar an entire profession as potential rapists – something with which the Australian Trucking Association has taken an understandable amount of umbrage – his hypothetical trucking company would indeed be in the clear both morally and legally if one of its drivers turned out to have molested a female passenger. Organisations are not responsible for their employees’ conduct outside of the workplace and the performance of their duties, and, as the eminently sensible feminist mantra goes, “the only people responsible for rape are rapists”.

So, in Pell’s hypothetical, if this rapist truck driver were caught, prosecuted, and punished for their crime, their employers would not suffer any legal consequences – although you would certainly hope that the company would create mandatory training for its remaining drivers in their anti–sexual assault policy in order to prevent future incidents.

The problem, of course, is that the Catholic Church in no way resembles a trucking company.

–

Vanishing Perpetrators And Silencing Victims: How The Church Protects Itself

But before we address these differences, let’s run the analogy out a little. The Catholic Church is a global organisation with a huge number of employees – 180,000 in Australia alone. Let’s try to imagine a trucking company of that magnitude, responsible for delivering 16.6% or so of the world’s total shipped goods (that’s the rough percentage of the human race that nominally belongs to the Catholic Church). Now let’s imagine that this trucking organisation knew that it had more than one or two problem truck drivers who were habitually picking up and raping women – just as the Catholic Church was aware that a not insignificant number of priests had been abusing the children in their care.

Let’s say that instead of acting to report these crimes to police or remove these ‘bad apple’ truck drivers from their jobs to prevent further harm to women, the company simply moved them to another route, just as the Catholic Church moved the convicted child rapist Gerald Francis Ridsdale from parish to parish in an attempt to distance him from allegations of sexual assault. Let’s say that the trucking company pressures the victims of these truck drivers into silence in order to preserve the trucking company’s reputation, just as Monsignor Leo Fiscalini allegedly urged one of Ridsdale’s victim’s family to stay silent about the abuse “for the church’s sake”.

Let’s then say that the trucking company starts addressing the issue only when forced to, and even then that it refuses to give the authority investigating the drivers’ crimes access to some of its internal documents, just as the Catholic Church is refusing to allow the Royal Commission full access to its own files in the Vatican.

I’m not a lawyer, but I’d hazard a guess that the management of such an improbable trucking company would be in some very hot water. They would, at the very least, have a prima facie case to answer that they were accessories to a number of crimes both before and after the fact.

But the Catholic Church is not a trucking company, and Pell is more than aware of this. Since the title of the Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse gives a neat summary of its ambit – which is to say that it is investigating how certain institutions have responded to allegations or proven incidences of child sexual abuse, rather than examining individual cases of abuse, which is a job for the criminal court system – Pell must know that his hypothetical trucking company would never have faced a similar commission in the first place.

After all, he swiftly clarified – no longer talking in hypotheticals – that if a church official had been informed that a certain priest might be sexually assaulting children and had failed to act, “then certainly the church official would be responsible”. The analogy therefore fails precisely because it elides the reason the Catholic Church has become embroiled in the Royal Commission: because the Royal Commission is looking for patterns of behaviour and weaknesses within systems rather than isolated instances.

–

Too Big To Exist: The Catholic Church’s Convenient Legal Loopholes

The analogy is useful, however, because it throws into light the immense differences between the Catholic Church and a trucking company. No trucking company could operate without being an entity for legal purposes, yet the Catholic Church in Australia remains an unincorporated association, which means it cannot be sued as a whole. (Its property and assets are held by a number of trusts.)

This is the crux of the so-called ‘Ellis defence’, a legal precedent that effectively quarantines the church’s assets from complainants in child sexual abuse cases; the complainants are still able to sue individuals who have abused them for damages in a civil case, but if that individual has negligible personal assets, as most servants of the church do, then there is little point in doing so. (Even though Pell himself has stated that the church should be able to be sued in such cases, this is not church policy, and the ‘Ellis defence’ remains in use by the church.)

Unlike a trucking company, which would pay a number of taxes on the profits of its business, the Catholic Church does not have to pay or receives exemptions from “the GST, income tax, fringe benefits tax at the federal level; land tax, stamp duty, payroll tax and car registration (state); and rates, and some power and water charges (local government and utilities)”, all of which (alongside similar concessions for other religious bodies) helps reduce Australia’s incoming tax receipts to the tune of $500 million per annum.

And, of course, no global trucking company hosts the uppermost echelons of its managerial team in a separate country (perhaps you could call it Truckistan?) that does not maintain extradition treaties with Australia, whereas the Catholic Church controls both the Vatican City State – a fully-formed country within the boundaries of Rome – and the Holy See, a statelike body that can maintain diplomatic relations with other countries on behalf of the church. (A fun fact about the Vatican City State: it was founded in a pact brokered by none other than Benito Mussolini.) A trucking company could not hope to claim that if a hypothetical rapist trucker had told one of his colleagues or superiors – let’s say a mechanic – about his exploits that the conversation should be free from reporting requirements, whereas the Catholic Church maintains the inviolability of the confessional seal.

Finally, there is no moral dimension to trucking work, whereas the Catholic Church positions itself as a source of moral wisdom through the teachings of Jesus Christ. A trucking company does not lure women into contact with hypothetical rapist drivers by promising them eternal salvation, but families and their children are drawn into contact with the church through the cultural power of its doctrines.

Pell’s truck driver analogy may have failed in the eyes of the public – at least if the Sydney Morning Herald’s letters page is an accurate reflection of prevailing sentiment – but it has also drawn attention to the enormous privileges that the Catholic Church is afforded in earthly affairs, ones that a trucking company, no matter how large or profitable, simply could never hope to possess. No matter your own take on the issue of whether God as construed by the Catholic Church actually exists, the fact that these privileges have been used to obfuscate truth and stymie the processes of justice should be seen for what it is – morally indefensible.

–

Chad Parkhill is a Melbourne-based cultural critic who writes about sex, booze, music, history, and books – but not necessarily in that order. His work has appeared in The Australian, Junkee, Killings (the blog of Kill Your Darlings), The Lifted Brow, Meanjin, Overland, and The Quietus, amongst others. He was the Festival Manager of the 2013 National Young Writers’ Festival and the Program and Production Coordinator of the 2014 Emerging Writers’ Festival.

–

Feature image via Roslan Rahman/AFP/Getty Images.