Why Do We Still Go Ape Over Tarzan?

After around 90 screen adaptations, there's another Tarzan film out now -- and even more in the works. What is it about this guy?

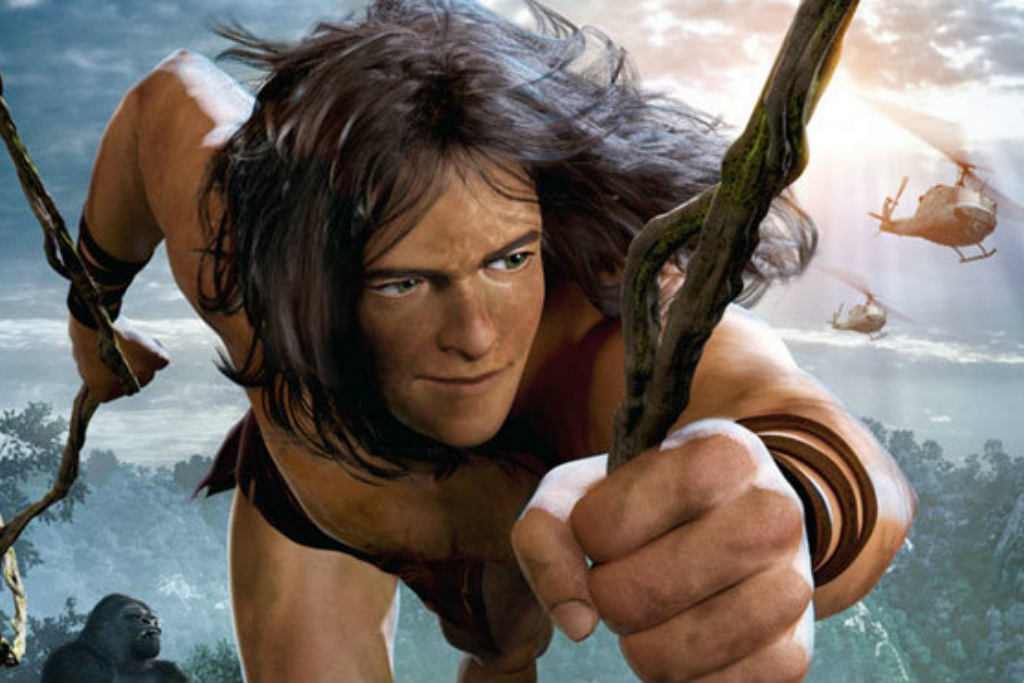

Gird your loincloths: another Tarzan movie is swinging into cinemas. Masterminded by German writer/director/producer Reinhard Klooss, this 3D motion-captured animation stars the abs-tastic Kellan Lutz as the titular jungle man.

Tarzan folds Edgar Rice Burroughs’ century-old adventure novel about a boy raised by apes into a nutty sci-fi tale of an asteroid with special powers. Klooss plays this far-fetched story as realist drama, with none of the songs, jokes or talking animals young audiences might expect. And in updating the action to the present day, the themes of class and colonialism that marked the original Burroughs story morph into contemporary concerns over corporate exploitation of natural resources.

This adaptation can’t free itself from the accumulated weight of the Tarzan mythos, audiences’ high expectations of animation, and other recent films that have handled similar themes much more deftly and originally. Tarzan owes obvious debts to Congo (1995), Avatar (2009), the recent mo-cap Planet of the Apes movies and even last year’s 3D family film Walking with Dinosaurs.

Yet, 15 years after Disney’s animated version – which sparked a lame stage musical adaptation – there’s renewed interest in the Tarzan story. Another live-action Tarzan movie is slated for 2016, starring Alexander Skarsgård (who also looks really nice with few clothes on) alongside Margot Robbie as Jane.

While Johnny Weissmuller’s Tarzan films are perhaps the most iconic – he played the role 13 times between 1932 and 1948 – the story was first filmed in 1918, starring Elmo Lincoln. Of around 90 film and television adaptations, more than a few have strayed from the original plotline; Tarzan, the Ape Man (1981) is a softcore version told from the perspective of Bo Derek’s Jane. Greystoke: The Legend of Tarzan, Lord of the Apes (1984) stars Christopher Lambert as the wild man taken to Europe to reclaim his title and birthright, with Andie MacDowell as Jane. And TV movie Tarzan in Manhattan (1989) has Tarzan come to New York to rescue his kidnapped chimp friend, meeting Jane, a taxi driver.

As if that weren’t enough, there’s also the Tarzan parody George of the Jungle (1997), and the female Tarzan, Sheena, who had her own film (1984) and a TV series (2000-2002) starring Gena Lee Nolin.

So what exactly gives this story its enduring appeal?

–

A Noble Savage

The figure of the unsophisticated but moral and honest person, at home in nature rather than in culture, has existed in the West for centuries. After all, ancient Rome’s foundation myth is a pastoral idyll involving a wolf and a rustic shepherd.

But by the 17th and 18th centuries, European intellectuals had begun to superimpose the classical Arcadia – a utopian ideal of unspoiled, bountiful, virtuous wilderness – onto the actual wilderness their countrymen were discovering and exploring. Literary romances including Kipling’s The Jungle Book, as well as travelogues including Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe, used the ‘noble savage’ trope to assuage the writers’ frustration about their own culture’s decadence.

Tarzan is a British aristocrat whose parents were marooned in Africa by pirates. But away from civilisation, he grows into a paragon of manhood: physically beautiful and capable, keenly intelligent and with an impeccable moral character.

Burroughs frequently contrasts Tarzan with his wimpy uncle, who was declared Lord Greystoke after Tarzan’s father vanished. As Tarzan gobbles raw meat and wipes his greasy hands on his naked thighs, Lord Greystoke fussily sends back his undercooked chops to his club’s chef, cleaning his fingers with scented water and damask. And as Tarzan terrifies his enemies with his victory roar, Lord Greystoke is addressing the House of Lords, “but none trembled at the sound of his soft voice”. Aw, nuts.

Today, Tarzan’s self-sufficient mastery of his natural environment has lost none of its allure. We rarely stray outside our comfortable urban surrounds, and our lives are increasingly mediated by technology. But through Tarzan, we can fantasise about communing with nature and rediscovering our primal selves.

–

Me Tarzan, You Jane

I laughed delightedly in the latest film when Kellan Lutz grunts to Spencer Locke: “Me Tarzan, you Jane.” This pantomime has become one of the key Tarzan tropes.

Tarzan’s love interest Jane Porter reflects old Judeo-Christian ideologies about women. Initially introduced as the daughter of a nutty explorer, she’s a damsel in distress whom Tarzan can heroically rescue, but his erotic interest in her also makes him recognise his own humanity. If Tarzan is an innocent Adam, Jane’s Eve lures him from his Eden.

Let us not forget that Tarzan is also about hot dudes wearing as little as moviemakers can get away with. In every era, Tarzan has been a lust object for women and gay men (NSFW link); while Jane teaches him language, he teaches her the language of lurve. In Bo Derek’s Tarzan, The Ape Man he’s completely silent and objectified; Jane is the real protagonist.

Tarzan is a fascinating canvas for changing male beauty standards. Despite a paucity of jungle razors he’s always clean-shaven, with a hairless torso. In the first half of the 20th century he was beefy, with short hair; from the 1980s onwards his body has become leaner, oilier and more chiselled, while his luscious locks are shoulder-length or longer. (No story has ever adequately explained his trademark loincloth.)

While the latest film painstakingly animates the graceful movements of Tarzan’s body, the awkward, plasticky character design gives him the absurdly tiny waist of a Minoan prince, and it annoyed me tremendously that not even wrestling a crocodile under a waterfall can dislodge the artful smears of dirt covering him.

–

The Tarzan Yell

In Burroughs’ novels, whenever Tarzan makes a kill he throws back his head and emits a “wild and terrible cry” that I imagine sounds sort of like Arnie’s scream in Predator.

Elmo Lincoln, star of 1918’s Tarzan Of The Apes, was the first to do it onscreen, complete with vigorous chest pounding. In 1952, he showed up on TV to show off both his manboobs and the unintentional hilarity of his Tarzan yell.

But Johnny Weissmuller had his own version, which his Tarzan uses to summon his animal friends:

Weissmuller insisted it was his own vocalisation, although journalists reckoned it actually spliced together several different sound effects (variously claimed to include male and female singers, a violin, a hyena, a yodeller and a hog caller from Tennessee).

It’s since become so integral to the mythos that subsequent Tarzans adopted it – Miles O’Keeffe in 1981’s Tarzan, The Ape Man; Tony Goldwyn in Disney’s Tarzan; and, yes, Kellan Lutz in this version. It’s also quoted in pop songs, from Baltimora’s ‘Tarzan Boy’ to ‘Jungle Boogie’ by Kool and the Gang.

However, the Edgar Rice Burroughs estate ran into difficulty when it attempted to register the Tarzan yell as a trademark in 2007. The official description uses musical notation: short, long and “semi-long” octaves, fifths and major thirds. However, the Office for Harmonisation in the International Market rejected the copyright application, arguing that even though the sound is instantly recognisable as Tarzan’s, its odd ululations make it impossible to standardise – and impossible to prove it has been copied.

Unfortunately, the Klooss Tarzan is much more like Lincoln’s yell than Weissmuller’s – an earnest attempt to nail something big that falls embarrassingly flat. Let’s see what Skarsgård can do.

–

Tarzan is in cinemas now.