Why Are We So Grossed Out By Scungy Old Underpants?

Old undies might disgust us for cultural reasons of hygiene or moral propriety. But it wasn't always the case.

Last weekend, I did a load of laundry that will keep me in underpants for about six weeks. As I was folding the clean undies to put away, I wondered — as I always do at this point in the laundry cycle — if I should throw some of them out.

It is maybe a good idea to throw undies away when they have holes, crotch stains, transparent fabric, fabric gone shapeless and baggy, faded colours, whites gone grey or yellow, and elastic fraying, detaching or losing its elasticity. Some of these are practical concerns. Worn-out undies aren’t pleasant to wear — we’ve all known the bunchy discomfort as an old, saggy pair of underpants scrunches over the horizon of your butt-cheeks.

But mostly, old underpants gross us out for cultural reasons of hygiene or moral propriety. And that’s what I want to investigate.

–

“She’ll See Through Me Like Grandma’s Underpants”: A History Of The Underpant

The original purpose of underpants was to strategically hide both men’s and women’s genitals from public view. Loincloths have been worn across cultures and eras, from the Japanese fundoshi to the Roman subligaculum.

Medieval European underpants were called ‘braies’ and looked like drawstring-waist pyjama pants. They were knee-length, but as fashions turned from knee-length tunics to puffy doublets revealing men’s hose (leggings), braies evolved into cute short-shorts. You tucked your shirt into your braies, and in turn tucked them into your hose.

If you were a man, you had to wear braies because otherwise your junk would hang out. Medieval men’s hose were two separate legs attached at the top to a waistband, much like today’s suspender stockings. It took Western fashion a surprisingly long time to invent the crotch seam.

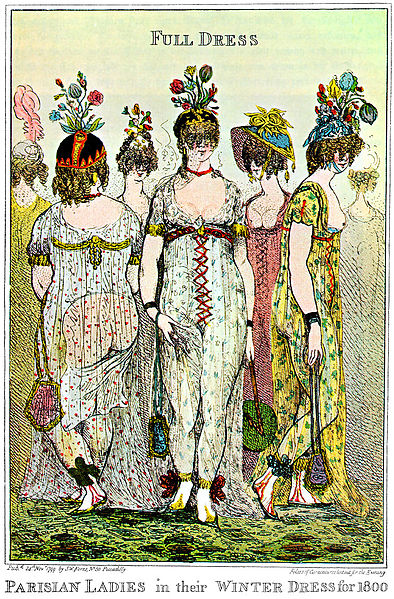

Medieval women, meanwhile, wore no undies at all. Catherine de Medici is supposed to have invented women’s drawers for horse riding, to preserve her modesty in case she fell off, but they still had a scandalous, cross-dressing vibe. Only at the end of the 18th century, when fashionable dresses were made from thin, semi-sheer chiffons and muslins, did drawers become morally necessary to prevent wardrobe malfunctions.

In the mid-19th century, when wire-framed crinoline petticoats were fashionable, drawers also protected wearers from leering onlookers. Unlike previous layers of heavy petticoats, crinolines were wide and light. They tipped forwards and backwards like bells, flashing stockings and petticoats; creepy dudes sometimes hid under staircases to peer up women’s skirts. And if a high wind got underneath, it could actually flip the crinoline upside-down.

From 18th century caricatures and 19th century music hall ditties to the Pase Rock song ‘Lindsay Lohan’s Revenge’, pop cultural mockery has always scared us into keeping our nads safely covered up. We get new undies to avoid getting shamed by an inopportune dacking, or revealing pubes and peen through holes.

–

“Stay Fresh… Keep Your Undies Nice”

We joke about ‘skidmarks’, pretending only gross slobs ever stain their undies and that ours are pristine. My friends still occasionally laugh about a notorious pair of stained men’s bikini undies discovered the morning after a house party, which no guest or housemate would admit to owning. But according to the wonderfully named University of Arizona microbiology professor Charles Gerba, “There’s about a tenth of a gram of poop in the average pair of underwear.”

That’s clean underwear, mind. Unwashed dacks carry about a gram of faecal matter. It stays on supposedly ‘fresh’ undies, because we’re being encouraged to launder our clothes with cold water and gentle detergents.

“I am very concerned about bacteria from soiled underwear transferring onto items such as tea towels, which are then used to wipe dishes,” says British food safety expert, Dr Lisa Ackerley.

–

Bathing Was Once Very Uncool

Between the early Renaissance and the late 19th century, people saw dirty underpants as welcome evidence that the undies were doing their job: effectively protecting their outer clothes from gross excretions. It was accepted that you’d soil your underpants, literally boil the shit out of them, and then get rid of them when they no longer came up looking nice.

During this time, bathing was uncool. People feared catching plague and syphilis from public baths and steam saunas, which were also disapproved of as hotspots for debauchery and prostitution. Even in private homes, doctors advised that bathing opened the skin’s vulnerable pores to the vaporous ‘miasmas’ that until the late 19th century were thought to spread disease.

Instead, people rubbed themselves down with perfumed cloths, sprinkled themselves with scented powders, and stored their clothes with incenses and pomanders. Basically, this was ye olde Lynx, Impulse and Febreze. These scents were so powerful that in 1639, when servants opened coffers belonging to Queen Anne of France, they had to flee the room until it was aired.

Cleanliness was judged not by the state of your body but by the immaculate whiteness of your linen undergarments, which began to peep from collars, cuffs and hems. But even at the end of the 17th century, most people only changed them once every three to seven days. And as John Safran reminds us, you can still wear your underwear four times without changing it: forwards, backwards, inside-out forwards, and inside-out backwards.

Only when socialite Beau Brummell became a fashion icon in Regency England did his toilette of fastidious bathing and several-times-daily linen changes catch on with England’s aristocratic set. The poor became disparagingly known as “the great unwashed”.

Later in the century, scientific discoveries introduced the Victorians to sepsis and bacteria. But you can’t sense germs, only stains and ‘odours’ — so in a way, today’s paranoia about bacteria, disinfectants and ‘freshness’ is as irrational and obsessive as the previous rituals warding off miasmas.

–

So You’ll Only Get Lucky In Nice New Undies

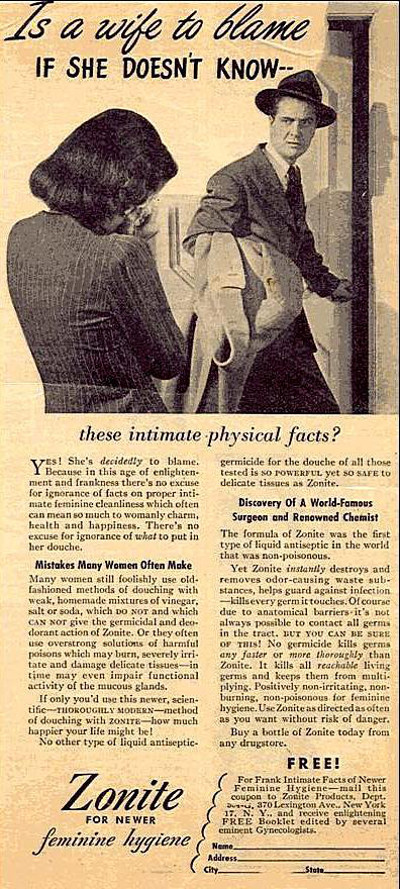

Bodily cleanliness has blurred into moral cleanliness… with the help of the advertising industry. Just as perfumers once claimed their products kept people hygienically clean rather than just smelling nice, so today’s toiletry, deodorant and ‘feminine hygiene’ industries promise to save you from slovenliness and sexual rejection.

‘Panty liners’ — thin pads you wear all the time, not just during your period — are now being marketed as an everyday way to “keep your undies nice” by preventing stains from “sweat” and “discharge”. “Rather than changing your undies, change your liner,” says Stayfree. Is that gross? I’m not sure, and Junkee commenters have been quite positive about these products.

It’s a fascinating revision of underpants: not as a cheap, disposable lining for other clothes, but as a garment worth lining in its own right, much as insertable ‘dress shields’ protect outer garments from armpit stains.

Perhaps we want to have ‘nice undies’ not for psychological reasons of comfort and cleanliness, but because, like our outer clothes, they’re meant to be seen. The idea of ‘lucky undies’ is not one tied to modesty: sexy underpants are often quite revealing… even see-through.

But only undies that are transparent when new are considered sexy and youthful. As Bart Simpson once acknowledged, undies so old they’ve gone see-through are for grandmas.

–

Mel Campbell is a freelance journalist and cultural critic. She is the founding editor of online pop culture magazine The Enthusiast. Her debut book, Out of Shape: Debunking Myths about Fashion and Fit, is out now.