What Happens To Your Online Presence When You Die?

And who gets to decide?

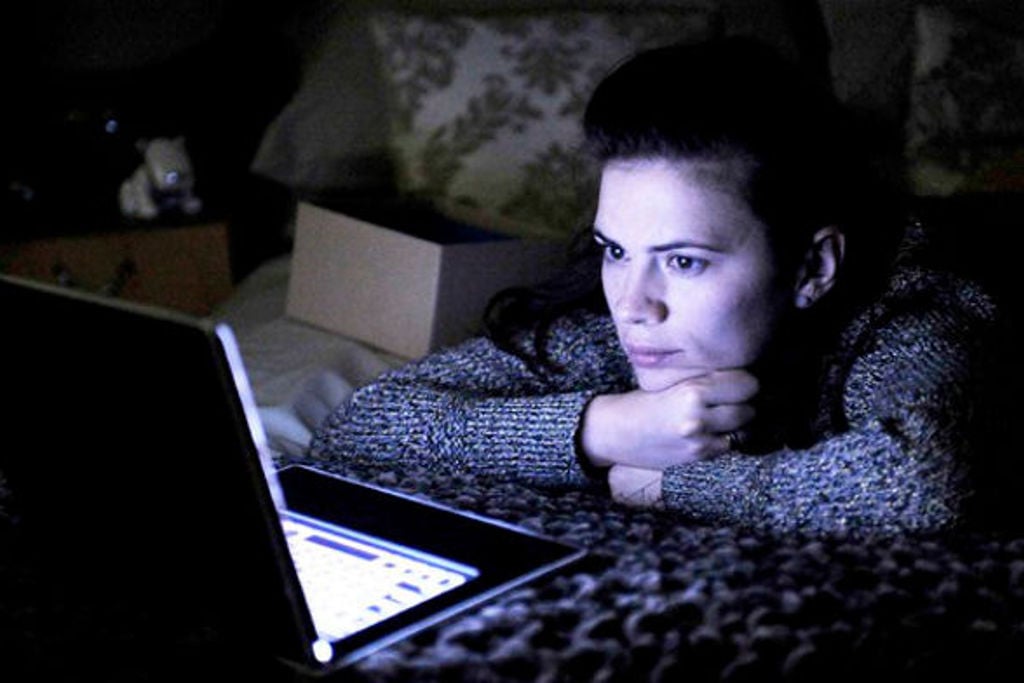

In one particularly dark episode of British TV series Black Mirror, a young pregnant woman’s newly-wed husband dies in a car crash. At his funeral, a friend who also lost her husband tells the young widow that there is a service that can mine all the data that a dead person leaves behind on the network, and reconstitute it as an algorithmic version of the deceased. The widow gives into her grief, and tentatively orders an algorithm husband. At first, she chats with him via text messages, but soon buys an upgrade so she can talk to him on the phone before finally upgrading to the premium service: a fully reconstructed body. In a sequence of events that seem inevitable, yet still shocking, they have sex and things go bad: a futuristic Frankenstein story.

Or maybe a contemporary Frankenstein story? A start-up called eterni.me is advertising a service that sounds almost exactly the same as the one portrayed in Black Mirror. Started by three engineers from MIT, eterni.me is a service that claims to be able to use the information a person leaves behind on the Internet to generate a virtual version of them once they die. The service aims to make “an avatar that emulates your personality and can interact with, and offer information and advice to your family and friends, even after you pass away.”

How To Live Forever Online

Eterni.me’s 37-year-old CEO, Marius Ursache, admits that the Artificial Intelligence algorithms he is using to generate these avatars are still too primitive for the type of scenario in Black Mirror, but believes that in thirty to forty years we might be approaching something like it. This is mainly because there will be far more data about dead people.

We have only been feeding selfies to the cloud for the last five or so years, and most of our baby photos are still stored in dusty photo albums. But what about babies born now? Just the other day a friend of mine from school uploaded a picture of her newborn on Instagram while she was still in the delivery room. She’ll probably continue to upload photos of him as he takes his first steps, goes to school … and then he’ll start taking his own selfies, and the cycle will be complete. She is unwittingly turning her son into a rich database for complex algorithms to play in.

Our baby girl’s 1st birthday party! #kidchella http://t.co/oNouMgGKoU

— Kim Kardashian West (@KimKardashian) June 23, 2014

We spend so many hours on the network, but so few people actually know what would happen to their Facebook account if they died tomorrow. Unless the deceased has organised a digital executor, it is up to family or friends to tidy up the online loose ends. Their first option is to delete the account altogether, removing all trace of the person from Facebook. But a request for deletion has to come from an immediate family member, who has to verify the action by proving their identity with a birth certificate, and their family member’s death certificate.

The other option is memorialisation, where the deceased’s account is basically frozen in time, leaving the option for friends to pay tribute and “share memories” on their Wall. To set up a memorial site, a friend must report the death, and provide a link to an obituary or death notice. Max Kelly, a former Facebook employee who lost a colleague to cancer, came up with the idea for memorialisation. He says it helped him “remember the good times we had and share them with our mutual friends”. Others feel that memorialisation is simply a way for Facebook to hold on to data after death, and that the decision to memorialise should be made exclusively by the family, not friends.

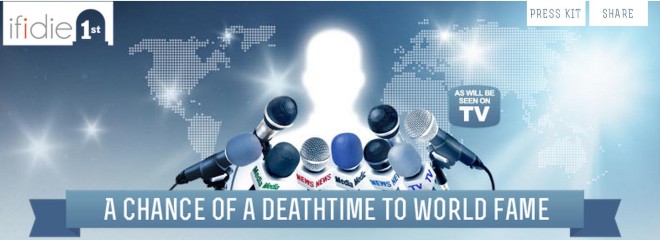

Another possible criticism of memorialisation is that the deceased doesn’t get to choose how they are presented after death. There are services that aim to remedy this. IfIDie, a Facebook app created in August 2012, lets you make a final video message that is posted to your wall after you die. The video is only posted if three trustees, selected by the person in question, all confirm that they have actually died. It is marketed as an opportunity to achieve posthumous world fame, a self-styled obituary that somehow goes viral.

I decided to try it. I downloaded the app, made my message, chose my trustees, and then asked them to confirm the very next day that I was dead. Sure enough, the following afternoon my final message was posted to my wall.

It didn’t get a single Like.

–

Up next: Dead ‘Likes’ and last tweets