It’s Well Past Time For ‘Unrest’, A Game-Changing New Doco About ME/CFS

You have to see this film.

When Jen Brea, a PhD student at Harvard, came down with a mysterious and debilitating chronic illness, she took to filming her struggles on her phone as a tool to communicate with her doctors.

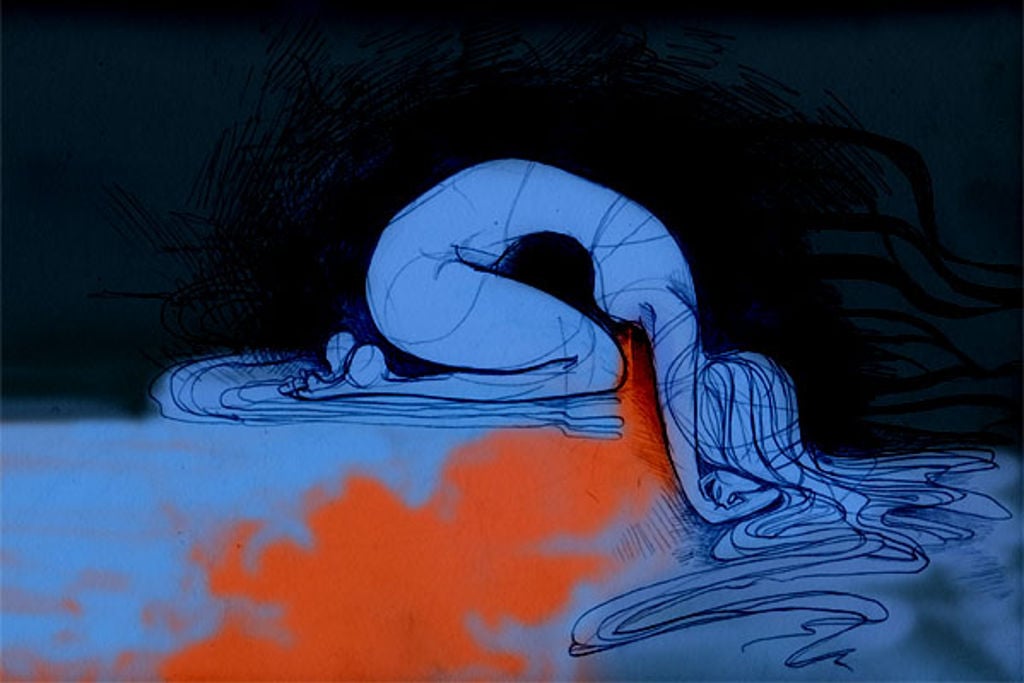

The symptoms of ME/CFS (also called myalgic encephalomyelitis or chronic fatigue syndrome) are both physical and cognitive. I can tell you from experience, it’s like having the flu with a hangover while someone turns gravity up to 100. There is no effective treatment. Symptoms worsen with activity, but are largely invisible and can be inconsistent, making them difficult to detect in a quick appointment with a GP.

The footage of Jen struggling to crawl across the floor, labouring to form simple words and howling in pain while collapsing from her wheelchair eventually became the foundation for Unrest, a powerful documentary on the collective trauma of a long-ignored patient community.

I first saw Unrest at the 2017 Melbourne International Film Festival with some trepidation. I’ve had ME/CFS for 12 years and my hopes for the film were high. We’ve been in dire need of effective media representation for decades, and a widely viewed, realistic portrayal of the illness could well be a game-changer in how sufferers are supported in our communities.

I wasn’t disappointed.

What began as a personal video diary morphed into a much broader tale exploring the impact of illness on personal relationships, the tragic failings of medical and research communities to take the devastating condition seriously, and dismissive public perception (Ricky Gervais’s jokes on the matter are shown in a particularly negative light). The film is both a record and an intrinsic component of an emerging patient revolution.

At the heart of it all, Unrest is a love story too. Jen and her endlessly supportive husband Omar invite the audience to share in an intimate emotional journey as they are forced to re-evaluate what they are to each other in the face of new limitations, and manage the impact of pity, disbelief and indifference coming from outside the relationship.

The raw honesty and vulnerability they’ve been brave enough to publicly expose is heart-wrenching, but also strategic. In drawing viewers into their private dynamic — the fears, hopes, insecurities, affection, anguish — they encourage the kind of empathy that has long been conspicuously absent in how people with ME/CFS are dealt with in the public sphere.

Jen was confined to her bed for much of the filming process but, through the magic of modern technology, she effectively networked with a broad patient community. As a result, Unrest takes an international perspective, capturing diverse personal stories.

In the film, we meet Jessica Taylor-Bearman, a young, creative British woman developing strategies to stay positive and sane while confined long-term to her bed.

Through Karina Hanson, who was forcibly institutionalised for three years (literally dragged from her family home in Denmark by authorities), we see how psychiatry’s historical appropriation of ME/CFS has resulted in the systemic mistreatment of physically vulnerable people.

It’s like having the flu with a hangover while someone turns gravity up to 100.

Through Whitney Dafoe, we see ME/CFS in its most extreme form, where eating, moving and interacting become intolerable. Whitney lies silent in a darkened room, tube-fed and wearing noise cancelling headphones to protect him from sensory stimulation which worsens his already alarming condition.

Whitney’s father, Professor Ron Davis, is a renowned researcher. He’s now devoted his career to curing his son, offering new hope to millions as he engages in desperately needed (and criminally underfunded) biomedical research.

Through the experiences of Leeray Denton, the film also explores the breakdown in family dynamics — a not uncommon occurrence when the pernicious idea that people with ME/CFS are capable of curing ourselves with a bit of motivation and grit takes hold. In contrast to Jen and Omar’s rock solid relationship, Leeray’s marriage falls apart. Her husband takes a well-meant but ineffective cruel-to-be-kind approach, believing she’ll be forced to stand on her own two feet if he leaves.

The film avoids becoming unrelentingly bleak by focussing on the strength and perseverance of the patient community. Now armed with the internet, people with ME/CFS are not so isolated as we once were, and have spent the last decade building up our activism, culminating in the Millions Missing protests taking place over the last two years.

We have either showed up to demand better research and support, or sent in empty shoes to visually represent the millions physically unable to attend. The protests happened all over the world, and the Unrest camera crews were everywhere, capturing the historical moment.

Jen remarks in the film that her old life is gone, but now she has a new one, and she has to fight for it. So here we are. Fighting with all we have.

Unrest recently came out on iTunes and I selfishly encourage anyone and everyone to see it, especially if you have a friend or family member with the condition or hold a position with any kind of power over our welfare.

In particular, I urge politicians, teachers, health professionals, social workers and anyone in the employ of the Department of Human Services, Centrelink, the National Health and Medicine Research Council, the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners or the National Disability Insurance Agency to make time for this film.

You have the power to make real change in our lives, and, after viewing Unrest, I expect you will be moved to take action.

–

Unrest is available on iTunes now.

–

Naomi Chainey is a freelance writer, presenter and community television producer with a background in disability activism and feminism.