Men’s Rights Activists And The Campus Left Faced Off At Sydney Uni’s Screening Of ‘The Red Pill’

The story of how one incredibly bad documentary is dividing students.

Men’s rights activists, anti-racism campaigners, the Israel-Palestine crisis and Mark Latham. Despite the lack of obvious commonality between these issues, they all cropped up last night when the University of Sydney became the latest battleground over a documentary accused of promoting “misogynstic propaganda”.

The university’s student union had refused to endorse a screening of The Red Pill, a documentary produced by filmmaker Cassie Jaye on the rise of the men’s rights movement, but a trio of student societies including Students for Liberty, the Conservative Club and BROSoc went ahead with their own privately-funded event.

Protests and petitions have led to screenings of the film being cancelled around the country, and last night’s screening at Sydney Uni was itself targeted by student activists, including members of a group known as Fascist Free USyd.

Supporters and opponents of the film clashed before the event kicked off, leading to one arrest. But were the tensions on display really just about one film or are they part of a broader cultural battle playing out between progressives and the far-right?

The Protests

About 50 protesters had gathered on Sydney Uni’s Eastern Avenue walkway, around the corner from where the The Red Pill was about to be screened. Opponents of the film had already succeeded in ensuring that the event wouldn’t be supported by the student union, arguing that “there is the distinct possibility that the planned screening of this documentary would be discriminatory against women, and has the capacity to intimidate and physically threaten women on campus.”

Even though the screening was entirely independently organised, left-wing students had mobilised to demonstrate their opposition to the ideas articulated in the film.

One of the organisers of the protest, Eleanor Morley, told me that “the film argues that struggles for women’s liberations have gone so far that women are now structurally oppressing men around the world. I think it’s quite laughable when you look at the serious disadvantages and discrimination face that women still face in society, such as the gender pay gap.

“It features a whole bunch of disgusting figures of the alt-right who hold deeply racist, homophobic and Islamophobic views as well,” Morley said. “We’re holding the protest because we want to make sure the film’s misogynistic, right-wing views are countered with a left-wing, anti-racist message.”

But Morley said the protest wasn’t about shutting the screening down, just articulating a different perspective.

According to the protest organisers, a film crew from Mark Latham’s Outsiders, Latham’s self-funded Facebook Live “show”, was there to record the action. When I asked Latham’s alleged cameraman whether he had been sent by the former Labor leader he said “I have no idea why I’m here” and backed away from me quickly, nearly tripping over a bench in the process.

The protesters used their chants to link The Red Pill to issues of racism and Islamophobia, which seemed kind of jarring given the film’s narrow focus on men’s rights activism and what it argues are the problems with contemporary feminism. But according to Morley, who is also an organiser with Fascist Free USyd, racism and men’s rights activism are both values embraced by emerging far-right groups on campus.

“It’s quite notable here at Sydney Uni,” Morley said. “Since the election of Donald Trump we’ve seen people walking around in ‘Make America Great Again’ hats, lots of racist graffiti and lots of Islamophobic signs posted around campus.”

The conflation of men’s rights issues and race wasn’t just confined to left-wing students, however.

At one stage the protest was interrupted (or hijacked?) by pro-Israel protestors. A group of students unfurled an Israeli Defence Force flag, for no clear reason, which led to some of The Red Pill protestors breaking out into spontaneous “Free Palestine” chants. One student attempted to grab the flag but was blocked by an organiser of the screening.

The scuffle ended pretty quickly and the protestors went back to chanting about the film. It was like the bizarre Israeli Defence Force interlude never happened.

The Battle

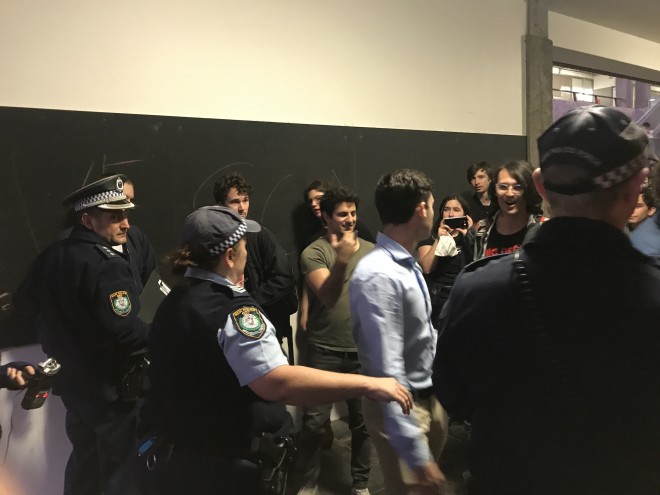

Up until this point the two groups — protestors and film attendees — had been kept seperate, but police were on standby in case there was a clash. And, of course, there was a clash.

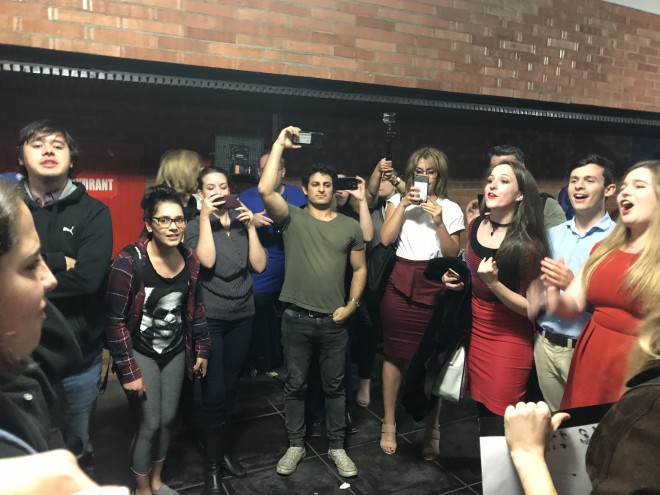

A few minutes before the film was scheduled to begin the protestors marched to the entrance of the lecture theatre hosting the screening, chanting “racists, sexists, anti-queer bigots are not welcome here”.

Anti-men's rights protests interrupt the crowd gathered for The Red Pill screening at Sydney Uni pic.twitter.com/GhcNGp2Pqd

— Osman Faruqi (@oz_f) May 11, 2017

“Goodnight alt-right” pic.twitter.com/0TkSi1Rodo

— Osman Faruqi (@oz_f) May 11, 2017

Some film attendees started chanting back, and they seemed to be enjoying the fact that something as simple as their decision to attend watch a documentary had sparked such a furious response.

One man wearing a t-shirt with the phrase “feminism is cancer” started dancing in front of the protestors. The event’s organiser, Renee Gorman, posed for photos in front of the angry crowd.

Gorman told me the event was her idea and she decided to organise it after finding it had been banned in Melbourne. “I watched it and thought it was really interesting, and thought it would be interesting to put it on here on campus,” she said.

“I think if you watch the film it’s actually not that intense, and it’s not worth the slander they’re putting against it.”

Conservative commentator Daisy Cousens, who was promoting the event on Twitter all week (despite not being a student at the university) appeared to be deriving a lot of enjoyment out of egging the protestors on.

A fight broke out when a member of Students for Liberty accused a protestor of stealing tickets to the event, but police quickly intervened. It was the only incident of physical violence I witnessed.

Students on both sides seemed happy enough to yell chants at each other, rather than actually punch on.

Given the protestors had already explained that they weren’t trying to shut down the screening, why exactly were they there? Morley said they were trying to articulate a “left-wing, anti-racist message” but the sole audience, other than journalists and the police, was the film attendees themselves. And they were loving the attention.

The Film

In 1999, The Matrix introduced the concept of the ‘red pill’. People trapped in a giant computer simulation can only free themselves by swallowing a red pill which destroys the artificial reality around them, revealing the fact that all of humanity is living in fake liquid-filled wombs like giant babies.

Eighteen years and thousands of angsty Reddit posts later we’ve got the The Red Pill: an incredibly confused profile on the men’s rights movement featuring an incoherent analysis of feminism, nonsensical statistics and a perplexing sequence on the Nigerian terrorist group Boko Haram.

The theatre was just about full, and more diverse than I was expecting. There were more women and people of colour than I thought there would be. Then again, considering I didn’t think there would be any, maybe that doesn’t mean much.

But the vast majority of the audience were young, white men. Phillip, a first year science student, told me he was attracted to the screening because he’s “passionate about freedom of speech” and doesn’t “engage with the feminist agenda”.

Phillip had only heard about the screening this week after student activists started promoting their protest, and told me it was “ironic” that the protests had boosted interest in the film. Another attendee, Hugh, had travelled from UNSW, where he studies engineering, to watch the film.

“I saw The Hunting Ground [a documentary on campus sexual assaults] and thought that was biased garbage. A lot of the stuff they were saying in that didn’t sound correct to me,” Hugh told me.

“The biggest issues are the increasing number of situations where feminists are asking for women to have greater privileges than men. I mean, it was supposed to be about equality, and who would argue with that? But you see a lot of of false information, like the pay gap. Who would believe that?”

Even though the film had started, the protest was still going on outside and chants would occasionally sound across the lecture theatre, despite the allegedly sound-proof doors.

Gorman and the crowd seemed to relish in the protests. It seemed less like this was a genuine ideological debate or a battle of ideas, and more a deliberate attempt at provoking or “triggering” campus leftists — the sworn enemy of student conservatives.

There are lots of other reviews out there that articulate the problems with The Red Pill, so I won’t go into a lot of detail about the narrative itself — except to say that it is a very bad film. And I’m not even talking about the documentary’s politics. It’s disjointed, lazy and, worst of all, incredibly boring. The film begins by acknowledging that some men’s rights activists have been accused of promoting violence against women. Like Paul Elam, who once wrote “should I be called to sit on a jury for a rape trial, I vow publicly to vote not guilty, even in the face of overwhelming evidence that the charges are true.”

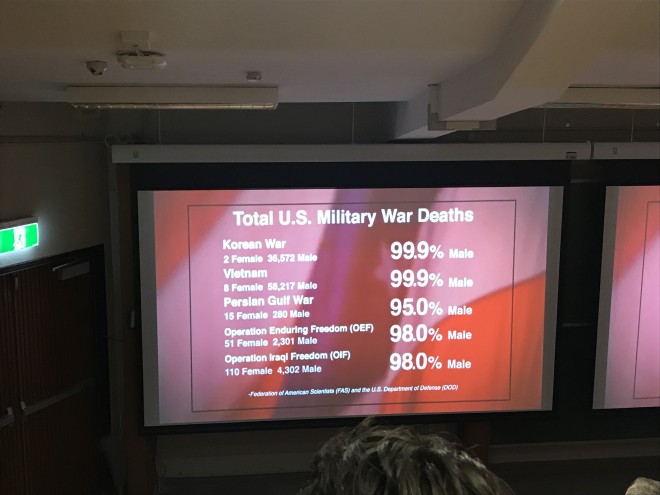

But the film never actually deals with this. It mentions the accusations levelled against men’s rights activists at the start, never engages with them and instead argues that men face discrimination because they are disproportionately more like to die in war, lose custody battles and become addicted to porn.

Even if those points are true, it’s completely irrelevant to the criticisms raised about people like Elam. What do alleged problems with family courts have to do with the fact that prominent men’s rights activists seek to defend rape?

Surprisingly, the audience didn’t even seem that into the film. The scenes that provoked the strongest response, either laughs or cheers, were the ones that featured protests against men’s rights activism. It shored up my view that the attendees weren’t necessarily full on ideological adherents to the specifics of men’s rights ideology.

No one was nodding along to boring rants about how men are actually the group discriminated against when it comes to reproductive rights and custody. What does an 18-year-old student actually have in common with a man in his fifties railing against the family court system?

The conversations I had convinced me that other than perhaps an obsession with free speech, this wasn’t a coherent group of politically like-minded individuals organised around a particular political viewpoint. More than anything, they were a reaction against the student left, who they saw as controlling the discourse on campus and in the media.

Of course, this doesn’t actually stack up. How can a young, white man studying at Australia’s oldest and most elite higher education institution seriously think that they are being silenced by “the left”? I doubt anyone left the screening more supportive of people like Paul Elam. But they might have left with a feeling that men, particularly conservative men, are being trampled on by feminism and need to fight back.

Why Does This Even Matter?

“The boycotts and moral blackmail of cinemas has only established the infamy of a film that would have otherwise been ignored,” Martin McKenzie-Murray wrote in The Saturday Paper.

I think this is absolutely true. The campaign against the film has absolutely increased awareness of it, and likely encouraged more people to watch it to see what all the fuss is about. But does that actually mean feminists and other activists should stay silent when something like this is released?

If Cassie Jaye and Paul Elam have the right to make a bad film that glorifies elements of the men’s rights movement, then protestors have the right to explain why their arguments are wrong.

However, it didn’t seem like that was what the protest organisers were going for. The action outside the screening was a demonstration of power and an attempt to antagonise, not an effort to articulate an argument.

I’m not trying to criticise the concept of loud, angry protests. I’ve been to plenty. I’ve helped organise them too. When the government is trying to destroy the higher education system as we know it, a targeted, fiery protest on national television can be exactly the right move, for example.

But if you’re trying to win the hearts and minds of university students, it doesn’t seem to make a lot of sense. Or at least, combative protests on their own won’t do it. I struggle to put myself in the mind of a first-year student afforded all the privilege in the world who still thinks he’s being silenced and trampled over by feminism. It’s not a unique conundrum.

These sorts of paradoxes are pretty common across politics. Think about the low-income Pauline Hanson voters worried about their economic situation supporting a candidate with dubious views on penalty rates.

In an era of political polarisation, it seems to make sense to try and understand what people are angry about and why. That way, instead of yelling at them, we can point out why their current preferred solution — whether that’s men’s rights activism or the far-right more generally — isn’t the right one.

–

Osman Faruqi is Junkee’s News and Politics Editor. You can follow him on Twitter at @oz_f.