Social Experiment Or Attempted Murder? The Morality Of Netflix’s ‘The Push’

Netflix's new reality show coerces people into pushing someone off a roof.

Can we be convinced to commit murder? That’s the question that The Push, Netflix’s latest reality special, aims to answer.

The Push sees UK mentalist and magician Derren Brown conduct an elaborate, choreographed, highly manipulative experiment: can he get an entrepreneur who believes he’s attending a legitimate charity fundraiser to push a man off a roof?

While Kingston chooses not to push the man to his supposed death, Brown eventually reveals that he has conducted the experiment three more times. And, each time, the participant went through with ‘the push’.

In their minds, they’ve committed murder… until Brown pops out in a “you got Punk’d” moment and declares that the whole thing isn’t real. He encourages them to peer over the edge to confirm that their ‘victim’ is actually fine, hanging from a harness off the side of a tall building rather than lying splattered on the footpath below.

The hour-long show, which debuted on Netflix last month, is disturbing at best and immoral at worst. It is a weird, uncomfortable, Black Mirror-esque deep-dive into the ethics of manipulating someone into committing a crime.

From Sausage Rolls To Murder

Chris Kingston attends what he believes to be a fundraising gala for a new charity, Push. He doesn’t know that he’s being filmed, or that every other person at the event is a professional actor. He doesn’t know that this very real series of events isn’t actually real. The night builds in intensity, as Brown has Kingston perform small acts of ‘social compliance’, where a person is urged, either explicitly or implicitly, to act a certain way in response to a request.

Derren Brown is calculated in this manipulation. He starts with what he calls the “foot in the door” technique: ask someone to do you a small favour, and they will be more likely to agree to bigger favours. For Chris, this first means labelling beef sausage rolls as vegetarian. It’s wrong, but if it means the gala will go smoothly, and they can raise more money for underprivileged kids, surely it’s okay?

But what start as small acts of submission build in intensity and consequence. Kingston is told the millionaire benefactor for the charity has died. He moves the (fake) dead body. He hides the body. He pretends to be the dead man when he is misidentified, giving a speech on his behalf. These acts of obedience grow, until they become crimes. Mislabeling sausage rolls turns into being urged to kill someone.

Facilitating A Social Experiment, Or Facilitating Trauma?

“That was awful,” says an actor playing a detective at the start of The Push. He’s just convinced a man to steal a woman’s pram and what he thinks is her baby (it’s actually a doll) from a café. In this moment, you feel sympathy for him, and the other actors. But this feeling soon evaporates and doesn’t return. At no other point in the show do the actors reflect on their own complicity, or the ethical question marks that hover over Brown’s experiment.

But perhaps the most unsettling aspect of Brown’s manipulation is his attention to detail. The dead body is the perfect example of this. It’s a hyper-realistic corpse created by Oscar-nominated special effects artists. It’s also a world first: not only does the body have to look realistic, it also has to feel realistic. This means moulding every part of the fake body from the actor: his limbs, ears, wrinkles and even the inside of his mouth. The fake skin and bones feel like real skin and bones. When the actor sees the fake version of himself, he’s dumbfounded. He can’t tell the difference.

“Participants in The Push all hide what they believe to be a dead body, and move that dead body. Most kick that dead body. Most push a man off a roof, thinking that he is falling to his death.”

In moments like this, it’s difficult to grapple with the culpability of everyone involved, and the sheer scale of the operation — Brown himself, the professional actors, special effects artists, a stunt coordinator, and celebrities like Robbie Williams and Stephen Fry who filmed videos to endorse the fake charity for the fake charity gala.

Criminally, it doesn’t seem like they’ve done anything wrong. After all, how can you be an accessory for attempted murder when you know it’s not really murder? Everyone (except the participants) knows that nobody is actually dead. They know that, even if he’s pushed, the man on the roof will be fine.

Morally, however, it’s difficult to justify. Brown claims that the purpose of the show is to illustrate the dangers of becoming too socially compliant. Yet he does this by dangerously manipulating people into being socially compliant. He tricks people into doing awful things to show the rest of us just how awful those things really are. Participants in The Push commit crimes. All hide what they believe to be a dead body, and move that dead body. Most kick that dead body. Most push a man off a roof, thinking that he is falling to his death.

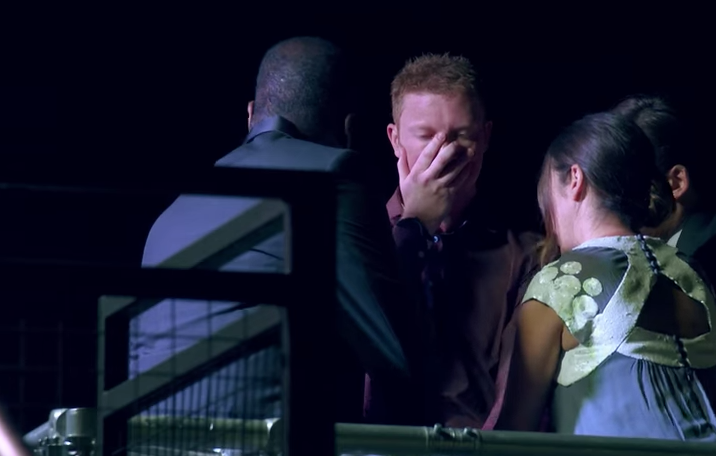

A man decides whether or not to commit murder. Tough call!

Brown is evidently skilled at the art of manipulation. The whole night is carefully choreographed, and he’s subtle in his approach to getting participants to trust the actors around them. One character introduces themselves with the last name ‘Kingston’, the same as Chris’. Brown explains that this builds connection; these undetectable deceptions add up.

The three participants who go through with ‘the push’ are visibly distressed afterwards. They cry and shake and look like they can’t believe what they’ve just done. Kingston also appears distressed at multiple points throughout the night.

Meanwhile, Brown sits in his production control room, smiling and explaining key moments as they unfold. He uses the word ‘murder’ to describe ‘the push’ multiple times, and seems weirdly pleased for Kingston when it looks like he may not go through with the ‘murder’. Kingston refuses to kick the (fake) dead body. Brown watches, then turns to the camera. “He might not even [push him off the roof], but good for him,” he says.

At the end of the show, all four participants feature in pieces to camera, giving bizarre testimonials about how the experiment has helped them. “It’s probably made me a bit of a stronger person like that,” says one woman.

But that’s questionable. Although Brown insists that “within five minutes of the end happening, they were fine”, people have raised concerns about the psychological impact of convincing people that they have killed someone. New Zealand’s Office of Film and Literature Classification has indicated it may review the show’s classification if health professionals or viewers express concern. And Bustle raised the question: “How does one recover from the psychological trauma of being manipulated into pushing a man off a building?”

The Unreality Of Reality TV

The schadenfreudian act of watching people be humiliated or distressed in the name of entertainment is nothing new. We love shows like Survivor, Big Brother, and I’m a Celebrity, Get Me Out of Here. Producers know that the worse the embarrassment or awkwardness, the better the ratings. In some ways, it’s a win-win: we indulge in the ‘guilty pleasure’ of watching others struggle, and TV networks cash in.

We all know that reality TV is unethical. In 2007, Big Brother came under fire after it failed to tell a contestant that her father had died. On a US season of Survivor, a contestant strategically lied about his grandmother dying. Then there’s the TV shows about ‘ugly duckling’ women getting plastic surgery, or substance abuse victims being allowed to drive while under the influence of alcohol or drugs.

But the key thing in these situations is, regardless of the ethics of the show itself, participants consented. In The Push, Kingston and the other participants don’t get that opportunity, which is why referring to them as ‘participants’ feels inaccurate. They don’t know they’re being tricked, so how can they possibly be participating, when the very word ‘participation’ implies a degree of choice?

We also know that reality TV isn’t really ‘reality’ at all. It’s scripted and deliberately cast and heavily produced and cleverly edited, but we’re okay with it. The Push emulates some of these editing techniques. The music is dramatic and we’re informed at regular intervals how many minutes remain until ‘the push’ in what feels like a parody of the ticking clock in the TV show, 24.

Deciding whether to kill someone looks very stressful.

But it also takes it a step further — a step too far. We can justify reality TV stars being humiliated because that’s what they ‘signed up for’. It becomes much harder when the protagonist has no idea that he’s the subject of an expertly designed hoax. Watching Brown in his roles as caster, producer and director pushes us up against the reality of his unreality.

Derren Brown isn’t a stranger to these ethically murky situations. He rose to fame in the TV series, Mind Control, in which he convinced people of unrealistic scenarios. And it’s also not the first time he’s convinced people to commit crime; Brown’s previous project, The Heist, saw him convince a group of business people to commit an armed robbery. He makes money off deception.

In The Push, Brown forces us to think about criminality and punishment, morality and ethics, reality and manipulation. And it forces us to ask complex questions. Are we okay with people being used as guinea pigs? Do we think it’s okay for reality TV shows to facilitate (and, in this case, encourage) crime? Is it morally bankrupt for Derren Brown to deceive people susceptible to social pressure without their knowledge or consent?

It’s difficult to answer these messy, knotted questions because they go to the core of who we are and what we think is right or wrong. But it’s important to confront them — and I think we draw the line when someone’s non-consensual trauma becomes our entertainment.

—

Brittney Rigby is a freelance writer based in Sydney. She is on Twitter.