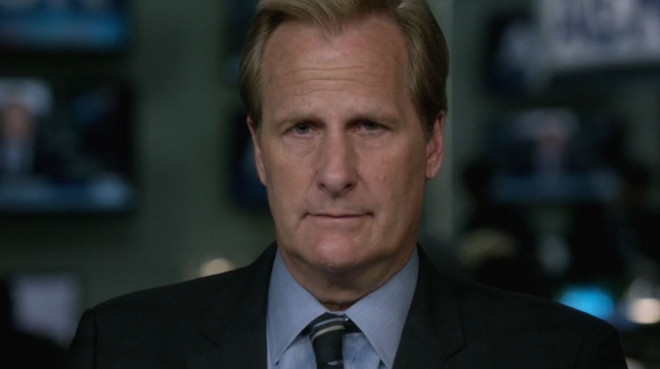

Was The Newsroom’s Final Episode What We Wanted It To Be?

Well, it did have one thing going for it: there was no maudlin montage.

This is a recap of the series finale of The Newsroom. There will be spoilers.

–

Life is bloody chaos, and we humans are our own worst enemies.

Between our tendency to work against our own best interests and the general randomness of the world at large, it’s no wonder we’ve always looked for patterns and inevitabilities, signs and gods. Once you hit that crisis of faith – whether it’s when you realise you don’t believe in God, or one or both of your parents, or the people in charge, or yourself – that aimless, abandoned feeling can be hard to shake. That’s why it’s nice to believe in fairy godparents, or an interventionist God – to think that there’s a benevolent hand guiding your path, someone who’ll show up when you’re at your lowest, sit you up and drag you kicking and screaming onto the right path, which was so obviously the right path in retrospect.

Aaron Sorkin, who is so fascinated by religious thought and ritual and the role of the paternal authority and influence in society (God is always a player in anybody’s daddy issues, whether they know it or not) loves this trope perhaps more than any other, particularly in his workplace settings. How many characters, in his oeuvre and just in this episode, are shunted wholesale into the next, better stage of their life by a figure of authority? How many torches are passed down within professional or personal relationships? Charlie’s death opens up the board for pieces to be moved: Mac into his old job, Jim into Mac’s EP role, Will into his roles as Noble Office Patriarch and confidant to the young musical prodigy.

More importantly, the Big Reveal is that Charlie was behind everything, all of it, the whole time. He prodded Will into giving a shit about the news he was reporting. He dusted off a PTSD-addled, exhausted Mac and sent her off to Northwestern to orchestrate Will’s rant. (Not sure if Charlie specifically told her to find a woman who looked like her, stand in front of her waving makeshift cue cards, and melt in and out of the ether to mess with Will’s sanity, but it seemed to work out for her.)

Everything unfurled from that point.

What’s irritating about this is how passive it makes the characters who are being pushed around. (And again, with the exception of Leona, the women are largely the ones being passively guided into their correct places, and men affectionately, authoritatively, do the guiding.)

Mac may be “the best in the business” — although we’ve been told that much more often that we’ve been shown it — but she’s right to squint tipsily at Charlie when she realises she’s being brought in at least partially as a provocation to Will – to be the muse, the passive thing which inspires a brilliant man to be truly great. It’s almost a subtler version of the models Pruitt hired for his party, whom he calls “living art” and means it as a compliment to them and evidence of his own Enlightened Attitudes.

Maggie has not gone after the job in DC herself; Jim pushes it in her direction, and then even piles another promotion on top of that when he takes a step up the ladder himself. (Are there seriously no internal hiring processes? Everyone can just point at their friends or fuck buddies and say “You job! Me saviour!”?)

Thankfully, Maggie insisted on doing what she wanted and on knowing what she wanted; I hope she meets a nice ethical hacker with a cute guinea pig in DC, or moves to Toronto and joins a garage band. Maggie and Alison Pill both deserve better than the patronising approval and dopey adoration of a bottle of kewpie mayo in a rumpled shirt. Pipe down indeed.

(It does matter how you got the job, by the way. Men just handing opportunities to women they’re banging, or women ushered into the corner office to solve some man’s PR problem – those are the kinds of narratives that contribute to the perception that women don’t deserve to be where they are, even if those women are absolutely qualified to be there.)

But ultimately, everything was about Will, yet again. The mission to civilise was as much about his self-actualisation as it was about communication; the arsehole Will who didn’t care what anybody’s name was and bumped proper news for rain in Rhode Island wasn’t a shit person because he wasn’t fulfilling his noble duty as a Newsman. He was a shit person because he missed his lady and was depressed.

Even Charlie’s funeral was all about Will: Mac leaves the service to make (not take) a call to her doctor specifically so Will can spend the full episode freaking out about becoming a father, wondering whether he’s civilised himself enough to make it work. He plays a song and heals the boy with music and gives a speech and gets to reveal both of Mac’s personal achievements. He bestows upon Charlie the greatest compliment he can think of – “great big man” – and goes back to work.

At the very least, this episode contained no Coldplay or maudlin montage (maudtage?); no romanticised, overwrought statements about making the best news they could ***~~~FOR CHARLIE~~~*** and no more grand speeches. (Except for when Neal comes in to lay his truth upon the earholes of the clickbait-film-crit idiot twins, which sounds like what happens when Aaron Sorkin makes a throwaway account and goes to town in a Buzzfeed comments section, before deciding it’s pearls before swine and copying it onto his folder titled Inspired/Inspiring Rants.) Just an office full of people, quietly, competently, going about their business.

At various points yesterday, we saw what the news can be. Actually, we see it all the time. Reporters are still going to war zones, to refugee camps, to dank file rooms, into Tor, and to island nations repurposed as prisons to try and find out what’s actually happening. They’re standing within shooting distance of men with guns, telling us as much as they can, correcting rumours, exercising their judgment as they decide what’s useful and what’s important and what’s merely interesting. Sometimes they die. Sometimes they are sued. Sometimes they’re imprisoned. Sometimes they make mistakes.

All the time, they – the good ones, the real ones – are asking themselves: what does this add to the conversation? Not “the conversation”, that insipid euphemism for whatever dogpile or hashtag is firing up Twitter, but the dialogue between power and media, between ourselves and those forces, between what we say we want and what we actually want and what we need to know about the world. Do I need to tell people about this? Why? Am I just adding to the noise? Do I think this information is important, or just that I will sound important saying it? It’s not madness to ask these questions and to try and make news. There will always be a place for that kind of reporting. Whether there will always be piles of money and glass meeting rooms and Louis Vuitton luggage for that kind of reporting is a different question; but journalism has a future, and it doesn’t necessarily look like this.

Sorkin wrote an op-ed the other day about the Sony leaks, berating entertainment journalists for reporting revelations like Jennifer Lawrence’s gender pay gap and the chummy, puerile racism of some excutive email chains. In the end, The Newsroom was one big op-ed, with a bit of white-bread sexual tension thrown in. Telling cable news to do real journalism is like lecturing Redfoo about how he hasn’t made an album better than Illmatic. Most stuff is just not very good or even necessary – 90%, if you subscribe to Sturgeon’s Law (and I do).

Real reporting, real news — beyond the stuff that Jon Stewart makes fun of, beyond the terrible stuff that makes up most of everything — is out there, helping us make some sense of all the chaos. Those who care enough about news and the priorities of smart, rich people to be mad at this show for not living up to its premise or promise now have one extra hour a week to go and find it in the real news, and to look back wistfully on the 10% of this show that had something useful to say.

–

Caitlin Welsh is a freelance writer who tweets from @caitlin_welsh. Read her Newsroom recaps here.