The Mild Achievers: Five People From The Class Of 1995 Who Did Terribly In The HSC And Are Just Fine

There's life after the HSC, even if you bomb.

Every year as high school final exams kick off around Australia, we’re invariably reminded of the high achievers of years gone by whose near-perfect marks kicked off dream careers in science, medicine and law.

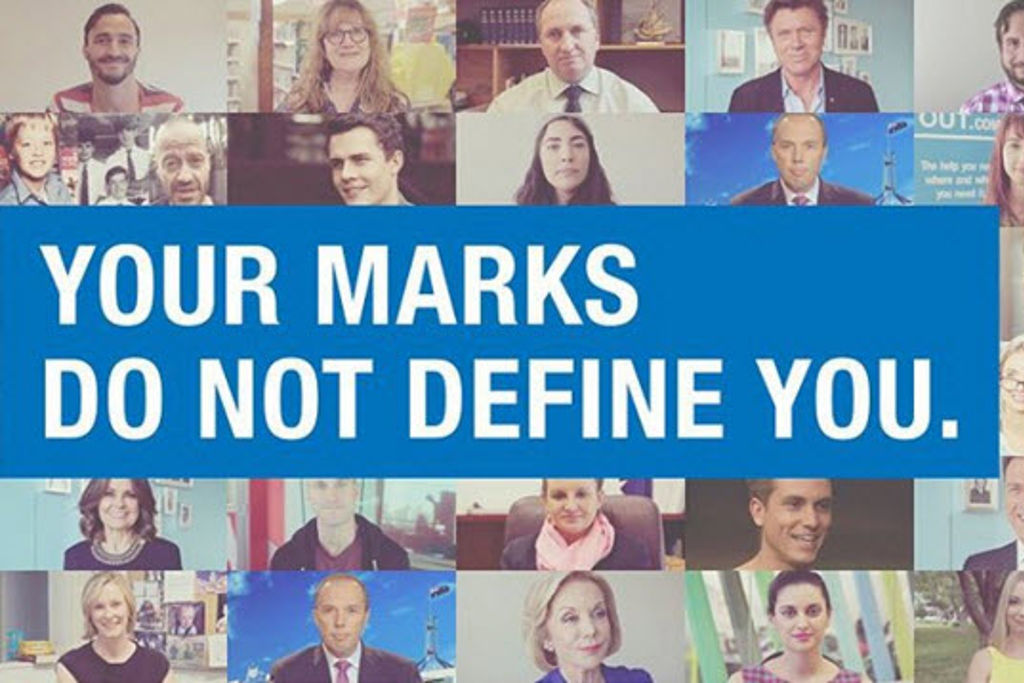

Sandwiched between championing the extraordinary career trajectories of the brainiest of recent decades and celebrating the Duxes of the 2015 cohort with fresh dreams for world domination, we rush to console and cajole exam candidates with reminders that these final digits do not define us. Reach Out’s #thereslifeafter campaign is excellent for putting this very specific snapshot in time into perspective with that elusive “bigger picture”.

Exam stress? Nerdy me in Year 12 will make you feel better. #thereslifeafter #TBT @ReachOut_AUS pic.twitter.com/zfFhJtDFtC

— Tom Ballard (@TomCBallard) October 16, 2014

So what happened to the kids who didn’t have an unwavering ability to prepare, focus and study? Those who felt like the schooling system didn’t support their interests or style of learning?

As student’s stress levels reportedly skyrocket and aspects of wellbeing form a downward arch resembling an algebra curve whose name we long forgot, here are some stories of people whose efforts 20 years ago were mainly mediocre — folks who invariably failed to be model students but whose lives turned out just fine, thank you very much.

–

Michael Brischetto – Co-Owner & Licensee, The Carrington Hotel, Katoomba

Michael went to a private school on the outskirts of Penrith. With three older siblings who were high achievers, he felt the pressure to do well and carried an expectation he would head straight to uni. Truth was, he could think of nothing worse than another three years of study. By mid-Year 12 he’d developed a keen interest in property, and through a school connection secured himself a traineeship before he’d even sat his first exam. Instead of focusing on algebra and the Periodic Table he’d sit in his room and work out how many houses he would need to sell to earn $100,000 in a year. On the day the HSC results were delivered by post, Michael sold his first house. It softened the blow of the shock of his mark (33.4). Ouch.

Michael thrived in real estate and on the thrill of closing a deal. He never thought twice about not going to uni and watched as many of his mates dropped out or failed. Just before his 21st birthday he bought the real estate agency he worked for, and over the next five years grew the business, taking over property management firms and opening new offices. He discovered he loved learning by taking seminars and courses in business and property development, building his skills and his passions on his own terms.

In 2004, an opportunity came up to own a stake in the historic but increasingly dilapidated Carrington Hotel. Michael knew nothing about hotels, other than he liked to stay in fancy ones, and after being involved as a silent partner he took the giant leap to sell up his real estate offices in 2006 and run the Carrington full-time. Beyond being an ongoing conservation project, employing over 100 people, The Carrington is also expanding to open a micro-brewery.

He’s forgotten (like most of us) what Cos and Tan mean, and how Newton’s Law works. They’re things that were tested in the HSC, but he says: “they never test you on is how to venture out into life beyond the school bell and rules. They never test you on how you can tackle the complex problems in life without a textbook or a tutor group.”

So if Michael could jump into the DeLorean and do things differently, what would he do? He’d pick the subjects he was actually vaguely interested in, not the ones that allegedly get scaled better. He’d have chosen Business Studies, not Physics; Music, not Maths Extension.

–

Marden Dean — Cinematographer

Marden was interested in emerging digital arts way back before wi-fi and laptops were part of the classroom, but he went to a public school with limited resources to support his passion. Like so many young people, he felt the system was designed for teaching to the test and maximising results rather than providing opportunities for how knowledge could transfer into real-world scenarios.

He had a couple of inspiring teachers who were interesting because they frequently strayed from the curriculum. It was far from Dead Poets Society, but being schooled about the world motivated Marden and his mates. He felt these teachers nurtured his potential, whereas others were simply going through the motions and ticking off syllabus outcomes.

Marden left school without a plan beyond having fun and exploring the world. Still scratching his head about what to do with life, he decided to start an Arts degree and taste-test a bunch of different courses. While many of his friends found their calling and made career strategies, Marden quickly got disillusioned with the corporate daily grind.

A small notice at his local film co-op saved him from second year uni. With zero experience, Marden white-lied his way into a job on a big budget American feature film. It was the start of an informal apprenticeship where he bounced from role to role on a number of large projects and got the taste for sailing along in a freelance lifestyle, where the diversity of the roles and projects tapped into his strengths.

Eventually Marden decided to get the qualifications to back his experience and enrolled in a three-year full time directing course at VCA. By the end of it, he worked out he didn’t particularly like directing, but he loved cinematography. He’s now in the middle of shooting his third feature film, with a range of credits from short films, documentaries and TV commercials to his name.

If he could do it all again, would things be different? Marden’s advice is to “stick to your guns and pursue what really excites you, even though it might not reveal any immediate transfer of skills or knowledge into a career”. His take on high school is to “use it for refining your interests and broadening knowledge”, without assuming that what you take interest in needs to be pinned to a definite career path right away.

–

Alix Hamilton Joannides – Director of Advertising, Louis Vuitton (Americas)

Alix’s report cards were filled with the old chestnut about her not “reaching her potential”. Unlike many, her self-confidence latched onto the positives of her potential but she simply didn’t see school as the vehicle to realise it. Instead, she was singularly focused on earning money and travelling. Her early experiences taught her lots about the important of financial security, and she felt work experience and exposure to career opportunities would help her find more authentic success than chasing HSC marks in subjects she’d loathe. Her interests always lay in the artsy subjects – she did Drama and Extension History and English, and was happy to abandon the perception that the only way to get good marks was to do positively weighted maths and sciences.

Ironically, Alix now works in a field which is very numbers driven, although she manages to blend maths with creativity as the Director of Advertising for Louis Vuitton across North and South America, based in New York. Her role involves managing the advertising investment for the brand, as well as determining visuals and campaigns that are right for the brand image.

So how did she end up working with one of the world’s most exclusive fashion labels? “Through no shortage of hard work and good fortune,” she reports. Her path involved a combination of study (she got a BA in Sociology eventually), working overseas, saying yes to every new opportunity, entering (and winning) industry competitions, staying late, being polite and not giving up. After starting an ad agency in 2000, she moved to LA in 2007 to manage the marketing budget for the launch of the iPhone. It took six months of pursuing the agency and flying to LA at her own expense for an interview to secure the gig. From there she moved to NYC a few years ago to take up the role with Louis Vuitton and married her Australian husband in March this year.

Her counsel for the class of 2015 is to get a formal tertiary qualification of some kind in the field you want to work in (if you’re lucky enough to know what that career is!), especially if you want to live and work overseas. If you don’t know, pursue extra study – take time to work out who you are and what things might excite you long-term.

–

Dr Hal Hancock – Medical Doctor, Royal Australian Navy

Hal grew up in Coffs Harbour, and his Year 12 was defined by a rainforest setting, an intermittently toxic relationship with his stepmother, a laissez-faire approach to formal schooling and misguided heartbreak. There were many rough patches, and assessment of his potential ranged from high to squandered. Beaches, books and playing chess got him through, but Hal says it “cost him five kilos and faith in my own abilities”. His final mark started with a 7.

The best choice Hal made was to start university in a place he’d had never been to – Tasmania. He completed a Bachelor of Science in Botany and Molecular Biology and landed himself a scholarship for his Honours year. Leaving the forest behind, Hal headed to South Korea to teach English for a year, returning to join the Navy as a medic for a couple of years before going back to uni to do Medicine. He’s moved around with his Navy role, completing his time as a junior doctor in Cairns. Now he’s based in Fremantle, where he’s a senior medical advisor specialising in diving medicine, mass casualty medical response co-ordination and remote area medicine, his job means he heads around the world to participate in international conferences and training exercises.

Want the doctor’s advice? Don’t believe your own bullshit, says Hal. “The stories we tell ourselves in the dark are powerful things, and it’s good to wander into the light and re-examine your thoughts and emotions. When your internal neural processing of neutral external input goes awry, it causes a lot of unnecessary hassle.”

–

Charlie Cousins – Actor

Charlie loved primary school; he rarely missed a day and despaired the days he was sick and couldn’t go. As the routine of high school set in, though, he remembers the feeling of playfulness and enjoyment in interactive learning slip away. While he says there were lots of great things about high school, as the years moved towards Year 12 he could feel a singular focus being put on head/brain learning – it got more factual, logical and linear, as well as more dissatisfying and stressful.

Charlie describes the change in schooling like “a challenge to see how many dry Saladas I could cram into my mouth”. Charlie was more interested in acting, singing and dancing, as well as what made people tick, think and feel, but later realised that his style of learning didn’t fit with the traditional education model. His result of 32.95 haunted his sense of self for a long time.

He auditioned for the country’s top three tertiary drama programs the year after high school. He wasn’t accepted into any of them, but got the feedback he needed to grow and improve. In 1999 he graduated from the Western Australian Academy of Performing Arts He says his acting career “hasn’t been easy – it’s a very competitive and difficult craft to master”. Like many actors, he’s had a bunch of part time jobs along the way – labouring, retail, child-care worker, nanny – all great experiences that he’s channelled back into his acting process. He’s currently playing a lead role in the Sydney Theatre Company’s Arms and the Man and when the season ends will return to shooting the fourth season of The Doctor Blake Mysteries.

Charlie’s advice is to “find your clan; people that understand you and speak your language but that challenge you to go deeper and be truer as well”. For many young people, high school feels like being a fish out of water; its only afterwards where many find people they’re truly comfortable with, but it can be more rewarding than a good ATAR will ever be.

–

Jocelyn Brewer is a psychologist and school counsellor. When she grows up she wants to be a Jillaroo.

–

Feature image via ReachOut/Twitter.