How Can We Solve Sydney?

Developers, architects, politicians and citizens are fighting over Sydney's soul, and only one side can win.

From the sky, Sydney is a sight that imprints itself on the memory of anyone lucky enough to see it. Most will only have a quick glimpse out the box window of an aeroplane as it descends into Kingsford Smith airport, but that’s all it takes. Below the quilt of clouds, the harbour city suddenly blooms — sandstone cliffs, beaches and bays, basking in golden sunshine.

Those of us who call ourselves Sydneysiders are even luckier – this unforgettable city is our backyard, and home. And now, heading for the prime of Spring – longer days, lucid azure skies and endless sunshine – it’s fair to wonder if this really is Australia’s best city.

But cities, like everything else, aren’t just about looks. Great cities, no matter how often they make ‘Most Beautiful’ lists – as Sydney so often does – must have something that gives the people a sense of pride and belonging, a feeling that their city is their home.

Does Sydney have that? Or has Australia’s largest city devolved into a Barbie doll; a pretty plaything passed around between politicians and planners, as something only to be sold, and profited from?

–

Sydney’s Public Spaces

The quality of a city’s urban public spaces — its parks, streets, squares and promenades, or the space that architect and author of the book Public Sydney, Philip Thalis calls “the physical representation of an open democratic society” — goes a long way to determining the make-up of a city’s soul. The quality of these public spaces, in turn, largely depends on whether they are owned by and accessible to the general public; whether there is a harmonious balance with private ventures; and whether there is genuine mixed usage, diversity, inclusiveness and intimacy found within them.

Sydney’s urban centre – stretching from Cockle Bay and Farm Cove along the east-to-west axis and from Central to the harbour side along the south-to-north axis – is a textbook example of how not to build and sustain public spaces. The CBD overwhelmingly resembles what renowned architectural critic and author Michael Sorkin calls a ‘Disneyland’ city: “an aura-stripped hyper-city, a city with billions of citizens but no residents…a place where everyone is just passing through.”

George Street – the spine of Sydney – is dominated by traffic, and almost everyone on the thin footpath is in transit, seeing the street merely as a means of getting from point A to point B as opposed to a destination in its own right. There’s little engagement with the environment, which is hardly surprising given it’s bordered by monotonous office buildings and retail – chain department stores, high-end fashion, souvenir shops. Rather than being in a living, breathing environment, walking down George Street feels as if you’re walking through a claustrophobic tunnel cluttered with neon lights, billboards, mannequins and Macbooks.

Photo by Fuzzy Images, under a Creative Commons License on Flickr.

The harbour blooms into view at the north end of George Street, but down around Circular Quay, little changes. The foreshore is occupied by monotonous, over-priced and tacky cafes, convenience stores, souvenir stands, franchised ice-cream parlours and fast food chains. The huge forecourt of Customs House is empty except for two high-end bars, and the fifteen-metre wide footpath bordering Alfred Street has been vacuumed of any vitality. There’s a scattering of community gardens, but in the absence of any real use for the area, they’re isolated and meaningless. The only people who frequent Circular Quay are tourists, workers and commuters, and once the working day finishes and the sun sets, it’s left to the seagulls.

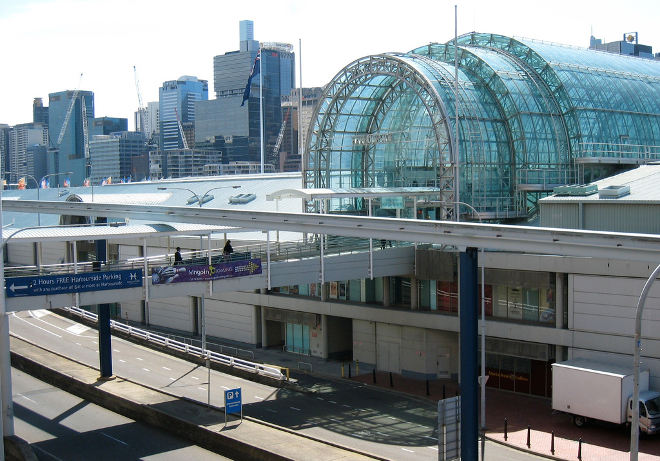

Then there’s Darling Harbour, described even by former NSW Roads Minister David Borger as an “urban failure”. Its history as a thriving commercial port for most of Sydney’s history has been forgotten, built over from the 1980s onwards by rushed, commercially-driven development projects. Motorways sever and alienate the precinct from the rest of the city, and buildings designed no better than car-parks cast a permanent shadow over the directionless walkways. There’s the sterile ‘Harbourside’ mall lit by the harshest fluorescent white lights, an equally large IMAX theatre, and a row of bars that are cordoned off by fences and hedges from the public promenade.

Photo by Alan Levine, under a Creative Commons License on Flickr.

Bear in mind that this is Sydney’s golden ticket we’re talking about here. The harbour foreshore is what millions of people come to Australia to enjoy; people who must leave distinctly underwhelmed by what we’ve done with the place. But for residents, the waste of public space is something they’ve had to get used to.

–

Barangaroo

Take Barangaroo, the disused maritime port on the western fringe of the harbour. In 2006, the state government green-lit a plan put forward by Hill Thalis Architecture and others to revitalise the area, proposing the foreshore as inalienable public space.

Three years later, and the Hills Thalis plan was abandoned in favour of another put forward by Lend Lease, which now includes James Packer’s $1.6 billion, 270-ish metre-high (the public hasn’t yet been informed of the exact details) hotel/casino, an as yet unplanned commercial and retail precinct, and a headland park. The original Hills Thalis team was excluded from the design process and afforded little opportunity for meaningful input; so much so that the architect at the head of the project quit after not being consulted for two years. No explanation was provided by the government for their decision to shift away from the original plan, but Independent Liquor and Gaming Authority chief Micheil Brodie noted in August that the approval process for the Packer casino was one of the fastest in history.

The end result — a development where public space is trumped by private interests, and high-end retail usage takes precedence over — will construct an invisible wall dissuading Sydneysiders who can’t afford to eat at expensive restaurants or shop at expensive stores from ever venturing there. Critics such as Dr Lee Stickells from the University of Sydney’s architecture department foresee the area becoming “a spectacular corporate quarter, with a carefully stage-managed sense of colour and movement”. To top it off, Sydney has lost the majority of the twenty-two hectares of land at Barangaroo that was — until recently — in public hands.

An artist’s impression of James Packer’s updated Crown proposal for the development of Barangaroo, from crownresorts.com.au

The overarching trend among places like Barangaroo where private interests trump public – which, sadly, comprise a huge chunk of Sydney’s urban centre – is their lack of diversity, intimacy and accessibility. The city feels increasingly glassed within shops and offices, the public space forgotten. Sure, it is a commercial organism – all cities are, almost by definition. But cities cannot just be business districts; they must nurture their public spaces and discover a harmony between these two often conflicting elements of urban life. It is the absence of this which vacuums a city of a soul and, for Sydney, can make it feel like just a Barbie doll, with only a pretty face to show to the world.

–

Enlivening Sydney’s Dormant Soul

But it’s not all doom and gloom. Even with projects like Barangaroo that repeat Sydney’s past mistakes, there is cause for cautious optimism that Sydney is gradually discovering and even reawakening its dormant soul.

Leading the charge in this respect is the City of Sydney Council and, in particular, the lord mayor Clover Moore. The Sydney 2030 strategy, produced in collaboration with Danish architect Jan Gehl, may be an ambitious one, but even if just a few of the plans contained within it materialise, Sydney will gain a personality that will make it like the cool kid at school that everyone wants to – and can – hang out with.

The most audacious plan in the strategy is to make a kilometre-long stretch of George Street between Bathurst and Hunter Streets pedestrian-only. No buses. No taxis. No cars. This has moved beyond being just a dream – it’s been endorsed by the state government, and construction is set to begin next year. The idea is to transform what is now a noisy, congested roadway into an inclusive walking space complete with public art, cafes, bars and restaurants will be afforded extra room for open-air dining; a project that will happen a lot easier once the numerous laneways and alleys that run off George, and have for too long been dark, seedy city pockets attracting only vomit-inducing smells, get the makeover treatment as well.

If you know where to look, you can see this revitalisation already underway. Parallel to Martin Place, nestled between George and Pitt Street, is Angel Place: a kind of template for what a new Sydney might look like. Stepping into it from the car, business and bank-saturated streets that surround it feels like entering a new suburb. Fairy lights and bird cages hang overhead, chirps and trills echoing around from hidden speakers. There are restaurants and cafes with outdoor seating, and concert-goers wander as they wait for a show to begin at the City Recital Hall. Tourists, businesspeople, commuters, music lovers, food lovers, art lovers – everyone is welcome. Hopefully, other wasted spaces – Barrack Street, Wynyard Street and the dingy Wynyard Lane that are quite literally across George Street from Angel Place – will match this success.

Image by Jam Project, under a Creative Commons license on Flickr.

Besides these bricks-and-mortars improvements, a surge in grassroots artistic efforts in and around central Sydney has taken hold. From public art exhibitions like the Elizabeth Street Art Gallery near Central Station to guerrilla music events like Reclaim the Streets, Train Tracks and Sunday Dub Club, the rising number of small-scale creative events being created by everyday Sydneysiders is — like the small bar boom before it — a promising sign. Alongside larger festivals like VIVID, Art and About Sydney and its associated events like Beams Festival, the Biennale and Sydney Festival, the creative and inclusive use of public space seems to be gaining real traction.

–

Taken collectively, these local government and grassroots efforts show Sydney’s got some life in it yet. Many parts of it have remained dormant thanks to the efforts of fast-bucked developers and state governments, but new openings for our city’s soul to emerge are appearing and spell a bright future for the harbour city.

There do remain some in power who want to plug these new openings. The City of Sydney Act was just amended by the Baird state government to give businesses two votes in Sydney council elections, a thinly-veiled attempt to unseat Clover Moore and rid the city of her progressive agenda.

But luckily, we seem to be making headway as more and more people discover that Sydney doesn’t just have to be a place for cars and commercial development. Sydney is slowly becoming our city. It’s for the wanderers, commuters, artists and tourists; for beggars, buskers, businessmen and bike riders. It is this soul which will give this city longevity and richness, culturally and economically. And those short-sighted politicians, developers and urban planners who are carelessly stifling this recent growth of Sydney’s soul need to remember one thing – even children eventually grow bored and tired of their Barbie dolls.

–

Feature image via Anthony Kelly on a Flickr Creative Commons license. The image has been resized.