When you live on an island with a conservative government that has the communication skills of a slogan machine assembled by a racist Doctor Suess, it’s hard to comprehend the breadth of the current global refugee crisis.

In Australia, the mainstream narrative has been politicised into an issue of national security, with our government cast as the heroes who are proudly swatting away boats, King Kong-style. If the government’s positioning is to be believed, the people on these boats are avaricious queue-jumping heathens, paying people smugglers to shop for the best country to resettle in. They’re possibly ISIS terrorists, too.

But with the crisis befalling Europe, this picture has been harder to maintain — especially with the images and stories that are trickling through: of 3000 displaced refugees occupying Budapest’s central Keleti station; of 50 refugees found dead, suffocated at the back of a lorry in Austria; and of the Syrian toddler Aylan Kurdi, whose body washed up on a Turkish beach alongside that of his brother.

Governments were forced into action, including Australia’s own. Germany and Austria announced they would be opening their borders to all refugees as a matter of humanitarian concern. In doing so, they waived the Dublin Regulation: a European Union law which means refugees must apply for asylum in the first European country they touch. The law was an attempt to force responsibility onto European nations to process refugees, and to ensure they would not be moved from country to country; but effectively, it put the most pressure on the countries around the external border of the EU.

It’s this policy that’s been central to the overcrowding of refugees in Hungary, where authorities have been so overwhelmed in processing the refugees who made it to Budapest that they shut down the trains to Western Europe late last week, causing chaos on the station’s platforms.

‘Chaos’ can’t even begin to describe what I witnessed at Keleti station, before finally joining refugees on the train from Budapest to Vienna, Austria.

***

Only ten hours after the September 4 announcement that Germany and Austria would be opening their borders, Keleti station is quieter and less packed than it appeared in the circulating images. A majority of refugees who had initially occupied the station decided to take literal leap of faith and walk 240 kilometers from Budapest to Vienna.

Those who remain set up at the station, to wait for a train to Vienna.

The exit to Keleti metroline at 10pm. (Photo © Carrie Hou)

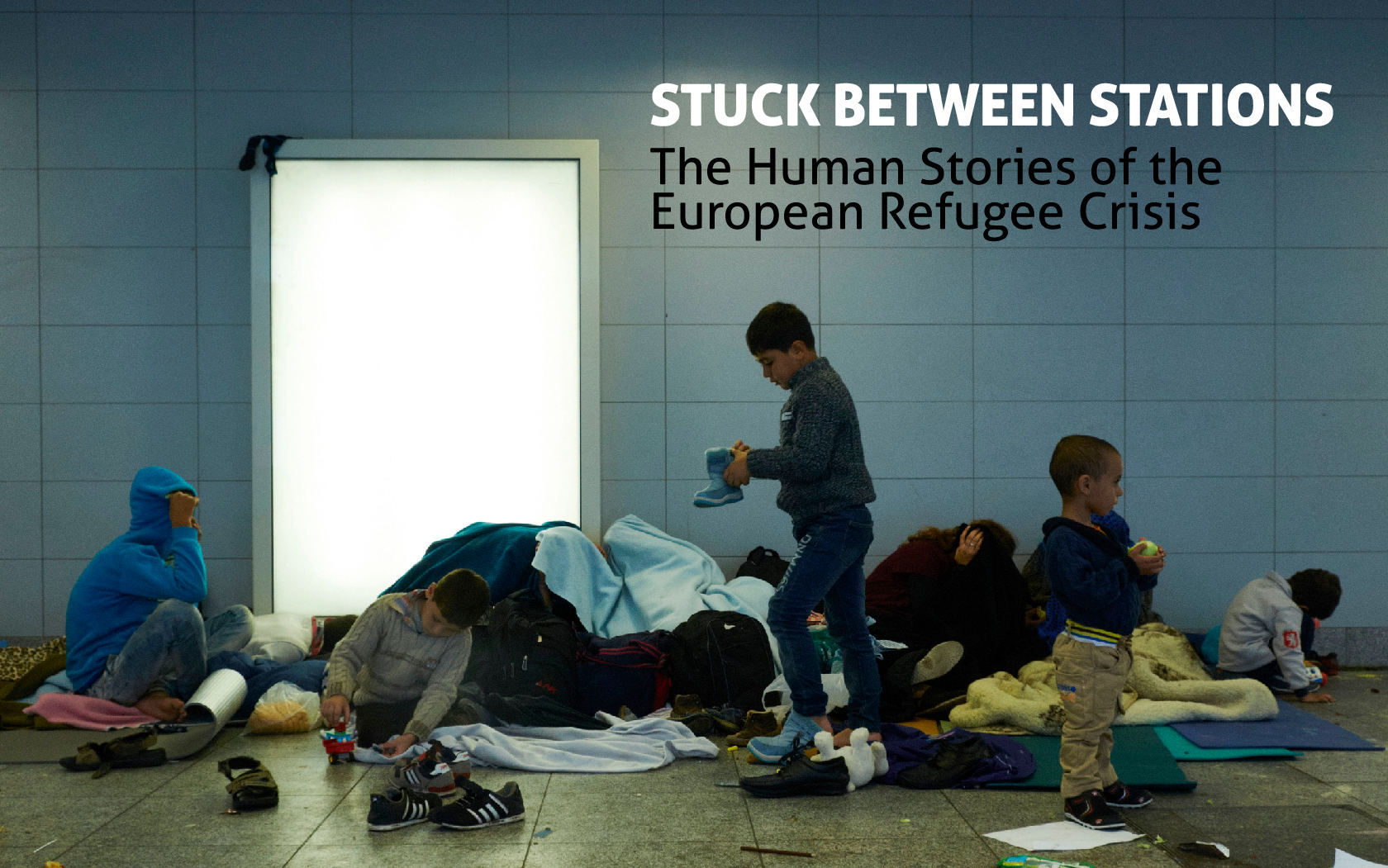

Keleti station is made up of both an underground metro and an over ground station, with a connecting exit that has been housing thousands of restless refugees. Warm, white-tiled and lit up by fluorescent lights, the metro’s exit point makes a perfect place to set up camp: half undercover for those needing sleep and half outdoor so the children can run around and throw soccer balls at each other’s heads.

Inside, there are makeshift mattresses strewn across the floor in parallel lines; tired refugees sleep under warm blankets provided by donations. It smells like pizza and feet. Outside, various organisations have mobilised: ‘Migration Aid’, a volunteer-based civil initiative, have set up a clothing charity and are providing various fresh water points for refugees to drink and bathe in.

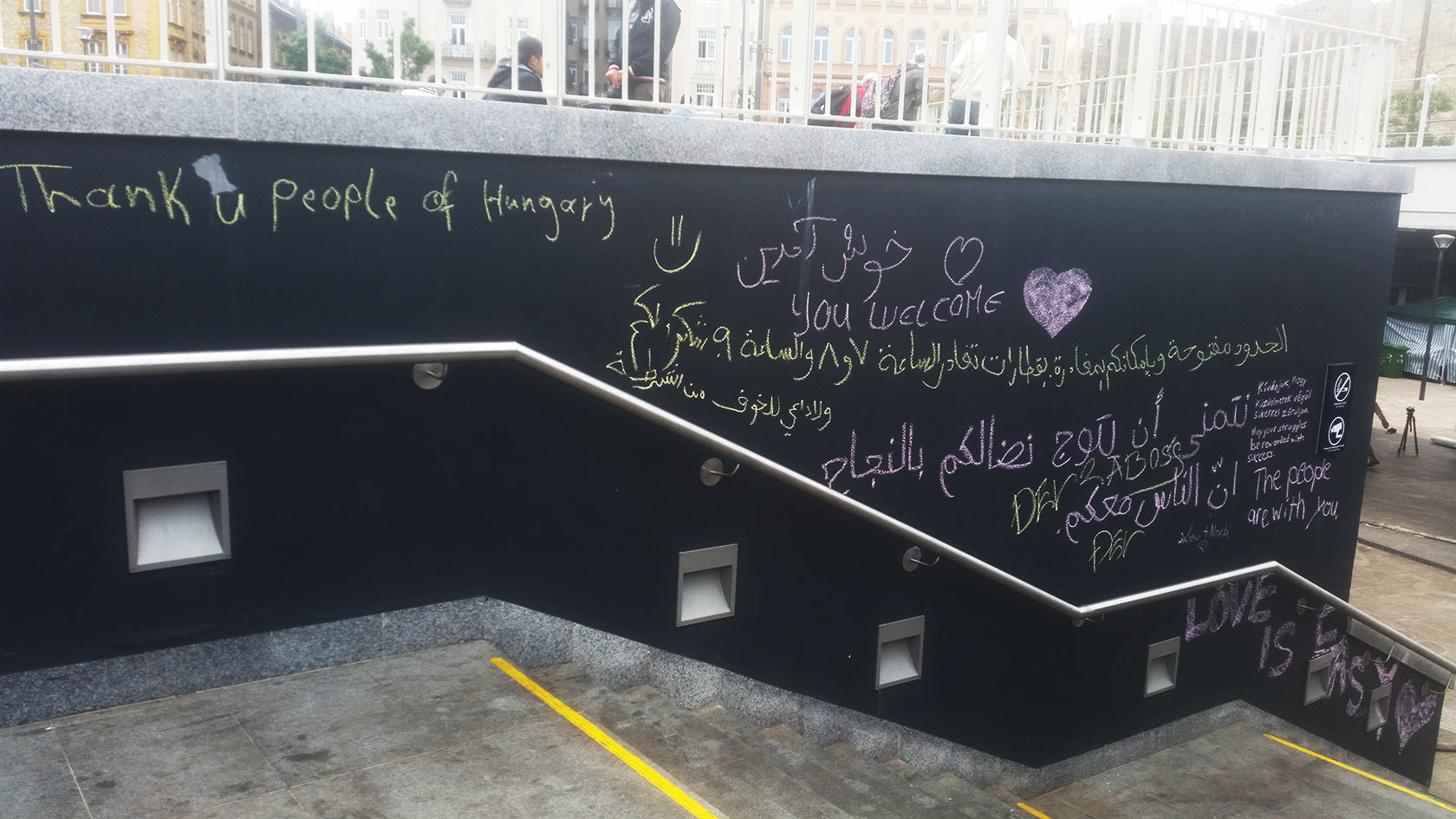

Objectively, the situation sounds dire, but the mood in this small space is unexpectedly welcoming. People are friendly, warm and eager to speak. Local and refugee children are happily chalking art against a stairwell wall.

Stairs leading to the overground international station. (Photo © Carrie Hou)

I meet Muhammad, a 32-year-old Syrian refugee who caught a boat to get to Europe. He’s sitting outside on a thin dirty mattress so that he can see the sky, smoothing his hair back, grinning from ear to ear and winking for one of the cameras of passing media. He sees me laughing at his modeling skills, and invites me over to offer me a jellybean.

“I’m going to Austria tomorrow,” he tells me. “I would have walked with everyone, but my feet hurt easily. I thought the train would be easier.”

I ask him why he left Syria.

“It’s bad. It’s how you think it would be. You hear noises and bombs every day now. It’s scary. Everyone is going. You leave, you survive. I have been everywhere – Turkey, then Greece. I want to eventually go to Germany. It seems like a nice place.”

Like most refugees, Muhammad has been seeking asylum for the past three months, fleeing Syria, which has been ravaged by civil war since 2011. Following the Arab Spring — massive democratic uprisings against President Assad’s tyrannic regime — the country hurtled into a sectarian war with a death toll of an estimated 310,000, leaving over seven million Syrians displaced. Muhammad is one in four million people who are fleeing.

Syrian refugees have overwhelmed neighbouring countries such as Turkey, Lebanon or Jordan, whose intake combined have resettled over three million refugees. This has caused many to keep travelling north, through the Mediterranean Sea on the same decrepit leaky boats and rubber dinghies that the Abbott government have nightmares about.

Refugees usually take a boat to cross the sea to Greece. From there, they move north through Serbia, usually stopped at Hungary from entering Western Europe. (Map © Matt Roden)

They first land in Greece, due to its proximity to Turkey and Libya, and make their way through the Balkan routes in hopes to reach Germany, where hostility and xenophobia towards asylum seekers is perceived to be lower, and where applications are more likely to be approved.

I ask Muhammad if he’d ever consider going to Australia. He laughs.

“No, no, there are too many sharks.”

I don’t tell him that sharks would be the least of his problems.

The Keleti overground, packed with refugees, tourists and police. (Photo © Carrie Hou)

The next day the Keleti’s overground station is packed. Signs have been put up in Arabic and Hungarian directing refugees to Platform Nine.

There, Hungarian police make a human shield as they calmly attempt to maintain order before a train to Vienna arrives. There isn’t any hostility between the authorities and refugees, but there is a sense of anxiety. They yell for “migrants” to not block the path to tourists, who are trying to make their way onto Platform Eight.

The word ‘migrants’ has been used by authorities, media and politicians across Europe to describe these refugees, but the term has been highly criticised by the UNHCR. It’s subtler then ‘boat people’ but it has the same sly political effect of inadvertently discounting their legitimacy as asylum seekers: in this case, it implies they are greedy ‘economic migrants’ instead. (The word ‘migrant’ also ignores the fact that over 72% of those who have been part of this crisis were found to be war refugees — begging the age old questions of whether our politicians are lying to us, or just stupid.)

When the train rolls onto Platform Nine, families impatiently wave their train tickets and push past authorities to board as quickly as possible, running onto the first carriage. These trains are not allocated just to refugees, so tourists who just want to see where the Sound of Music was filmed wait patiently at the back.

The packed train to Vienna. (Photo © Carrie Hou)

Inside, the train is overcrowded. Compartments, which cater to six people, are filled up with nine. Most people sit on the floor in the corridor to get a breath of fresh air. Teenagers dangle outside the train window, waving at anybody outside who will wave back.

I share a carriage with Ahmed and his family. They are Iraqi. Ahmed’s English is strong, but for more complicated words like “torture” or “persecution” we need to use Google Translate. He offhandedly tells me how he’s slightly deaf in his right crumpled ear because he had acid thrown into it. He does not want to go into more details of the people he’s lost during the American intervention in Iraq because it “makes his heart hurt”. He force-feeds me chocolate as the journey continues.

An hour into the ride, three border-police interrupt us. They don’t bother checking the photo of my Australian passport, but Ahmed and his family have a problem. The police ask for registration papers in English, and wristbands that were supposed to be given to them at the train station upon the purchase of a ticket.

Ahmed and his family are confused, as am I. Of the approximately 200 refugees I estimate to be on this train, I haven’t seen a single wristband.

“I don’t think anyone on this train has them,” I tell them. The border control look at me skeptically and take me outside the compartment.

“Are you a journalist? Working for a charity? What are you doing here?” they demand.

When they finally leave, Ahmed is anxious. He keeps asking me over and over if the train is going straight to Vienna. In fact, most people in our carriage come up to ask me the same question. No doubt they’ve heard about the trains that were rerouted to asylum seeker detention camps on the border of Hungary days before. I assure them that we’re going to Vienna; the Hungarian authorities guaranteed me when I showed them my ticket. Otherwise, I would be on a completely different journey.

Many asylum seekers fear being detained in Hungarian camps. Like in Australia, refugees are forced to wait in detention, living in awful conditions until their asylum claim is processed. Depending on their gender and country of origin, refugees are either placed in ‘open’ or ‘closed’ camps in Hungary for an uncertain period of time. Both of these camps have been condemned by Amnesty International.

I meet a father named Alaa from Syria, who is travelling with his seven-year-old son Fathi. Alaa reenacts for me, much to Fathi’s chagrin, how tightly he held his son when authorities attempted to lure the two of them onto a bus to a camp. His friend Mahmoud tells me how much he detests Hungarian authorities, showing me how they forcefully bound him and his family into handcuffs like criminals, despite their cooperation with the police. Another refugee, who would not give me his name, shows me how he and his friends burnt their fingertips to remove their prints. They were involved in organising a riot at one of the camps, he says, amassing over one hundred people to push down a fence in order to flee. I’m reminded of the riots and the hunger strikes on Manus Island, where two refugees were desperate enough to sew their lips together in order to show Australia how awful the conditions of our detention centers were.

Paranoia escalates when we reach Hegyeshalom station — a tiny stop on the Austria-Hungary border — and are told to change trains to get the Vienna. When stepping off the train, authorities begin to divide the refugees from the tourists, putting them on separate trains heading to Vienna.

“Are you with the migrants? If you are go the left. If you aren’t, go to the right with the tourists.”

Ahmed is worried, and wants his family to follow me. It makes sense; they wouldn’t put a nosy 5”2’ Australian girl onto a train that was headed to a camp. I travel with the rest of the migrants, and assure him we’ll reach Vienna in no time.

By the train, locals have mobilised with water, warm clothes, biscuits and bananas. This small altruistic gesture significantly comforts the refugees, and picks up the mood.

“Safe journey! Austria welcomes you!”

This is an understatement.

When our train finally reaches Vienna there are Dutch-Arabic translators waiting on the platform. With A4 paper signs sticky-taped on their chest indicating that they speak Arabic, these volunteers are young and sincere. As the train doors open they answer the questions being thrown at them quickly, and begin directing the refugees to walk up the station. In a hesitant line, they all disembark.

And all of a sudden there is thunderous applause.

At the front of Vienna Station are a line of locals, volunteers and police cheering. They hold signs reading “REFUGEE WELCOME”. As we walk past them, people hand out water, bread, fruit, cigarettes, coffee, and clothes, as well as bowls of potpourri and balloon animals. There are carts of donated clothes and food. Various charity organisations, like Time To Help EU and Global Dignity and Human Rights, have set up stalls for health inspections, charity bins and even a place to donate train tickets to migrants trying to reach Germany. The mood is ebullient.

Martin, an Austrian volunteer, tells me that it took less then twenty-four hours to mobilise this set-up, due to the overwhelming outpouring of support.

“The people in Austria get it,” he says. “Central Europe has been ravaged by plenty of wars and displaced generations of people. The people who are most affected by it are ordinary people who want to live ordinary lives. You would think that politicians would learn from their own history.”

Austrian-Syrian teenagers stand in solidarity, thanking Austria for its kindness. (Photo © Carrie Hou)

Since opening up the borders over the weekend, Hungary’s Prime Minister has already told Germany to stop taking in refugees, as his government believes many “economic refugees” from Serbia are joining those from Syria and Iraq, crossing from Serbia into Hungary to make it to Germany. Hungary announced that it plans to “seal off” its southern border with Serbia, as several hundred refugees broke out of camps. After accepting over 12,000 refugees, the Austrian government is also revoking the emergency measures that allowed thousands of refugees stranded in Hungary to enter their country, in an attempt to counteract the chaos that ensued over the weekend. Tension has arisen in the Greek Island, Lesbos, as refugees attempt to flee to Athens. Bavarian authorities are warning that they’re reaching “breaking point” after an influx of 18,000 refugees. In the UK, David Cameron promised to resettle 20,000 refugees from Syria, and France announced they would take in 24,000. After Germany and Austria’s decision to open up their borders, there has been uncertainty over Europe’s heavily criticised Dublin Regulation – but so far there’s no solid solution to replace it.

Back home, Tony Abbott has smugly pointed to Australia’s lack of a refugee crisis, as proof that Europe should follow his ‘stop the boats’ policy. No children have washed up on our shores, after all. He claims that it’s thanks to our hardline approach that Australia is in a position to accept 12,000 extra Syrian refugees. And he’s finally able to fufil his dream, and join a US-led airstrike in wartorn Syria.

Here’s the thing, though: this crisis is global. Refugees are like eggs, and our nations are the baskets. If one basket is taking in less than it can, or suddenly becomes xenophobic and closes up altogether, it puts more pressure on all the other baskets — often under-resourced baskets, with less bargaining power and more economic troubles.

In fact, deterrence policies and closed borders are what lead to crises like Hungary in the first place. As The Project‘s Waleed Aly pointed out quite eloquently, just because you turn around the boats it doesn’t mean they magically disappear. Those leaky boats still navigate the seas and overwhelm countries with less capacity to take in refugees, like Jordan, Hungary or Greece. The crisis is global. Leaders around the world can’t close their borders and bury their heads in the sand.

Coming up with a pragmatic, feasible asylum seeker policy is going to be complex, of course: an absolutist closed or open door policy will prove chaotic. But what should be at the forefront of the discussion when finding a solution is simple.

That is: for whatever reasons, war, persecution, and tyranny exist in this world. It’s tragic and condemnable, but it’s not going away. The people who are affected the most are never going to be the suburban middle-class swing-voters, who are worried about immigrants stealing their jobs, or terrified of terrorists disguised as refugees invading their shores. The people who are affected the most are people like Muhammad or Ahmed; people haunted by the rattling of gun shells and bombs ripping apart their homes.

By some exquisite luck, we belong to a country that has none of this. We have freedom of speech, freedom of religion, the right to vote, due process and some damn good meat pies. The desire for these people to flee by whatever means to a prosperous place like this — free from violence and persecution so that they can live their lives in peace — isn’t a threat or a nuisance, or even all that complicated.

It’s simple. It’s human.

–

Carrie Hou is a Law/Media student from Sydney who is currently travelling around Europe.

Feature image by Pierre Crom for Getty.