Story Club: Rob Carlton Relives Bullshitting His Way Onto An Extravagant, Disastrous Movie Set

Neeeeeever do this.

Story Club is a monthly live event held at Giant Dwarf Theatre, where Australia’s finest raconteurs — politicians, comics, writers, commentators and musicians — tell the audience a story based on that month’s theme.

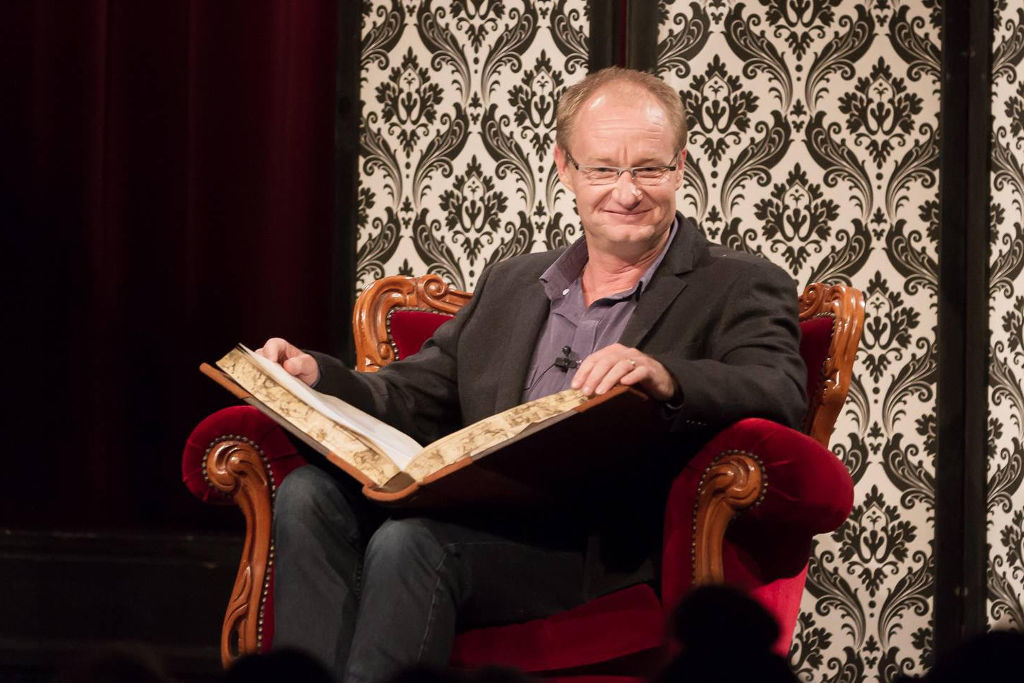

To celebrate the launch of their brand new podcast, they’ve shared with us the transcript of a tale told by Logie-winning actor and comedian Rob Carlton, based on the theme ‘The One That Got Away’. You can listen to the podcast here; an audio version of Carlton’s story is embedded below.

—

I’ve long believed the single most compelling force in any situation is legitimacy. Work hard, be true to yourself and you will prevail. Ironically, to gain legitimacy, sometimes you have to tell a little bit of bullshit. Sometimes, you have to tell a lot.

I’m 25 years old. I’ve been living in Los Angeles with my buddy Dean for six months, and we are poor. And a bit sad, to be honest. Sad in both the ways: we were sad to look at and sad to be. We needed something to change when the phone rang and Dean picked it up: “Yeah. Yeah. I might know someone. I’ll call you back.”

“That was my mate Pascale,” Dean says. “He’s making a film in Melbourne, he starts filming in eight days and his continuity expert has just dropped out. He’s desperate. He’ll pay $1800 a week cash, he’ll fly you back to Australia and then back here, and all you’ve got to do is continuity on a feature film. We’ll be able to buy you a book on it probably, so you’ll know what to do, and I can tell you a bit about it too. All I want is ten percent of your wage as a hook-up fee. What do you reckon?”

To be clear, continuity is an expert’s position on a film. The stuff you think you know about continuity, how much wine is in the glass … that’s the easy stuff. You’ve also got to monitor and record screen direction of actor’s sight lines, as well as their entrances and exits to make sure action cuts together. You’re matching dialogue, wardrobe, make-up, blocking, stunt action and cinematic techniques. You’re timing every scene. You record all the camera lenses and filters. You describe all the shots used to cover all the scenes. You are the information conduit between four different departments, as your daily production report is the Bible of where all sound and vision can be found, and in what order they’re required to put the film together.

You are the steady unflappable force always at the director’s side. There’s a lot of paper work, a lot of fine detail, you’re often put on the spot with a whole crew staring at you. And there’s a few other things as well, so now you try remembering where the fuckin’ wine level was. Not so easy now, is it?

Happily I didn’t know any of this about continuity when I said to Dean, “let’s give it a crack.” Dean called his mate Pascale: “Good news Pascy, he’s one of the best, and he’s available”. And so, 36 hours later, I kid you not, I’m flying out of LAX to Melbourne in my new capacity as the international continuity expert stepping in at the last to save this small but noble Australian film.

I was excited. The director of photography (the DOP) was a hotshot American being flown in too: he had credits on some big US films including the Home Alone franchise. But excitement would have to wait. I had one 14-hour flight to learn a whole profession from a book: The Role of Script Supervision in Film and Television, which is what they call continuity in the US. I had to get cracking because I also wanted to squeeze in an inflight movie.

After dropping my bags at home I went straight to the production office, we had so little time. The setup was impressive. They’d taken over a series of buildings and an entire laneway off Sydney Road in Brunswick. The pre-production buzz was electric. The camera department were shooting tests; production design were creating the world of our movie; the composer was on site punching out hard electronica; the whole place had a punk, grunge, but moneyed vibe about it.

Pascale, the director, this little Aussie Italian dreamer, was so grateful and happy to see me. He said he was honoured I’d been willing to clear my busy international schedule for his film. He was sweet so I patted him on the back and nodded supportively, as though to say, “We’ll get you through this little man”. He introduced me to the producer as “the guy that’s flown in to save us”. I didn’t resist. The producer nodded at me. I nodded at him. Two equals, he and I, each with a massive job to do.

When it was finally my turn to speak, I started by lying my head off. “The airport lost all my bags. All of them. All my continuity items that I own have now been lost by the airline people. Where’s the runner? Runner, you go and buy me all of the things on this list. All of them.” Happily, Chapter Two of my book had a comprehensive list of all the things I would need which I’d scribbled on a piece of paper somewhere over the Pacific. Some items were surprising and I had no idea why I would need them, but the runner questioned none of it so I assumed it made sense to him. The producer was impressed with my ability to command one of his subordinates. I was impressed with me too.

That afternoon I faced my first real test. I was with the second assistant camera woman, Julie, when she asked: “which slate system are you going to use? The American or the Australian?” Okay, truth, here, now: I didn’t know which system was better. I didn’t know there were two systems. I didn’t know which system it was I knew.

A huge rumble of a massive motorbike saved me. “That’s my boss,” Julie said as she ran out to greet this American rock star of a DOP. His long brown hair and charisma shimmered as he chucked back some breath mints while dismounting the Harley Davidson he’d demanded while he was in Melbourne.

When Julie got back to me I’d snuck into the toilet and discovered my book had been written and published by Americans. “We’ll be using the American slate system,” I said. “Why? The Australian system is much better.” I didn’t blink: “I’m well aware of the deficiencies of the US system compared to the Australian system, but I’ve got limited pre-production, so let’s stick with what I’m comfortable with.”

There was the briefest pause where she allowed herself to rightly think “cock,” before she said: “Well it’s your call, you’re the continuity expert”. I nodded, equally thrilled and disgusted with myself.

Alright, the shoot. It would be true to say the film got away from us. It would be equally true to say that it exploded in our faces so spectacularly and ingloriously I bore witness to a devolution of the human spirit. The obvious stuff broke first. The schedule. How you can be a full week behind after only two days filming is a secret shared only by Pascale and Baz Luhrmann.

Financial pressure always weakens a producer, so when I told him by my timing estimates we were making a nine-hour movie, the poor man never thought in a straight line again. His efforts to arrest the slide combined with his nervous breakdown had him forcibly ejected from the set by the middle of week two. Pascale, whose own wife now took the producer reins, told us there was nothing to worry about. He was as wrong about that, as he was about everything else.

You see, drinks on wrap were tradition by day two, and as you know, when the drinking starts the fucking begins. And fuck they did. At first it was just quickly and horridly in small offices late at night. But soon it spilled onto set, at lunch, specifically behind the grips truck.

By now a heady mix of sleep deprivation, paranoia and lovers quarrels took control of the crew, which meant that shouting matches and human weeping were constant companions. The most spectacular demise of any one person was, of course, our American DOP from the Home Alone franchise. He was, pure and simple, fucking nuts. The breath mints he’d been scoffing turned out to be a medley of Xanax, Zoloft and Sudafed, so he literally went from shouting his orders like an army general to moments later sleeping like a newborn just behind the camera.

That might be film-making American style but in Australia you’re going to get called on it and it was his gaffer, the guy that works closest to him, that made the call. Why he chose to call it on a sloping tiled roof three stories high I will never know, but to watch those two giant men roll and wrestle and punch and swear at high altitude was the most beautifully barbaric and dangerous and pathetic thing I have ever borne witness to.

Oh, almost forgot, the American DOP and I were in a car crash too. After a night shoot he’s driving me home in his car (they’d taken the bike off him when they discovered his narcolepsy), and he forgot what country he was in. Took a right turn slap bang into oncoming traffic. Just as the oncoming car’s headlights lit us up, he was staring at me, this once great man, in bug-eyed confusion. For some perverse reason that image still makes me smile. His working holiday in Australia had come to an end and, you would have to say, not on his terms.

The next day on set was perhaps my favourite. The resignations the illicit sex demanded began in earnest. I thought the exit of the DOP would staunch the wound, but no. Instead it inspired us to bleed out. One after the other, with the dead eyes of the guilty and beaten, people made speeches about commitment and honour and hard work and then they’d quit. I loved it. It was so piss weak. No, you’re not honourable, you’ve been drunk for three weeks while you’ve been shagging your coworker. Own it. But they didn’t.

By the end of the four-week shoot there were only a few of us originals remaining. Like the Wiggles. For me, I’d had the best time of my life. To absolve myself I’d told two people the truth of my credentials. One was Julie the camera assistant. To hear her immediately say “Ah, that’s why we’re using the American system” was priceless.

Other than that, I never got found out. On the contrary, I found opportunity in chaos. I’d added script editor to my duties midway through the shoot, and by the final week Pascale was so fatigued I’d started writing new scenes of my own which we’d shoot to fill the gaps in the story. On my final day of the shoot, I wore a tuxedo to celebrate.

But it didn’t end there. A month later Pascale and his wife offered me a considerable sum to write their next movie. Pascale agreed the one he’d written had some holes in it. I took their money and wrote that film and by the time their faces were splashed over the front pages of the newspapers for embezzling funds out of a supermarket in Brunswick, I was driving across America in my Oldsmobile station wagon with the money I’d legitimately bullshitted out of them.

—

The Story Club podcast, featuring stories from Kate McClymont, Eddie Sharp and Jonathan Holmes, is released every week. Subscribe here.

—

Story Club happens monthly at Giant Dwarf in Redfern. Their next event, featureing Alex Lee, Patrick Magee, Rebecca Huntley and Chris Taylor, is on November 2. Click here for details.