Recap: Why Did ‘Doctor Who’ Just Break Its Own Time Travel Rule?

The Doctor can't fix every problem he encounters by simply hopping back in time, right? In last night's episode, that rule got thrown out the window.

For a long, long time, time travel in Doctor Who was just a device to get you to the next story.

At first, the show tried hard not to deal with paradoxes: the best part of time travel narratives, where something would manage to cause itself. For instance: someone finds an apple on a table, goes back in time, and leaves the apple on the table for themselves to find in the future. If it’s the same apple going around in a loop, where did it begin? Where did it come from?

But as Doctor Who went on, it grew increasingly comfortable dipping into the paradox vault. In 1972’s Day of the Daleks, guerilla fighters travelled back through time to prevent a future Dalek invasion of Earth, and unwittingly created the very future they were trying to avoid. In 1989’s The Curse of Fenric, Ace saves her infant mother in World War Two, essentially bringing herself into existence. In 2005, Rose knows to send herself the “Bad Wolf” message only because she kept seeing the Bad Wolf message she would eventually send.

It’s an unavoidable part of the time travel narrative: the infinite circle, the grandfather paradox. And this week’s episode begins with this very idea.

“For just five easy payments, you can own this brand new single from one of Germany’s fastest-rising stars.”

Addressing us directly through the camera, the Doctor tells us a bizarre story about a time when he went back to meet Beethoven, but discovered the composer had never existed. So the Doctor’s ways of fixing this hole in history was to take the sheet music of Beethoven’s symphonies and works, and publish them himself, in Beethoven’s name*.

But, the Doctor says, the real question is this: who actually composed the music in the first place? It’s an anecdote that has no obvious connection to the story, so it’s clearly there to flag that we’re about to get into serious paradox territory. Something in this story is going to cause itself.

This week’s Before the Flood is the continuation of last week’s Under the Lake. After the futuristic underwater encounter with the alien ghosts – sentences like that are why I love this show – the Doctor has decided to pop back in time to find out what really brought them into being.

It’s both a welcome and a frustrating narrative. Welcome because we have to wonder why he doesn’t use this obvious option more often; frustrating because if he did actually do it more often, it would sap all the drama out of every single story. Every damn week, writers would have to establish a reason why he couldn’t simply duck back and fix things. That sort of ongoing caveat takes up a lot of real estate, which is why Doctor Who addressed this a long time ago.

In Steven Moffat’s The Girl In the Fireplace, the Doctor dismisses the idea of simply fixing things with the TARDIS by proclaiming “We’re part of events now!” – a piece of dialogue that is infuriating and delightful in its nonsense. (It is, in this sense, one of the most Doctor Who-ish lines ever written.)

Instead of having to come up with an excuse each episode as to why he can’t simply use the TARDIS to save the day, the show just made it an unwritten rule that he couldn’t: it would cause too many unspecified paradoxes. That meant if he wanted to break that rule, the writers had to come up with a reason why. And it had better be a good one.

So why are the events of Before the Flood an exception? It’s really not clear. Consequently, as entertaining as the surrounding episode may be, we can’t quite shake the nagging feeling that it’s, well, cheating. “That ghost was actually a hologram I created because I saw myself do it” makes enough sense on a logical level, but not on a dramatic one. It provokes an “oh…” instead of an “aha!”.

Before the Flood is an odd beast. It’s dramatic without being particularly tense. It’s interesting without being especially compelling. It has a straightforward narrative, but its overall intention never seems entirely clear. It’s apparently about how sometimes events can circle back around and cause themselves, but it’s a thesis that feels way too much like an afterthought, as very little in this two-parter seems geared towards exploring this idea.

Doctor Who is often at its best when it’s being several things at once, but it also fumbles badly when it’s throwing everything at the wall to see what sticks. And that’s the real paradox the show is struggling against.

–

Questions to Ponder:

- Did O’Donnell set up an actual future plotline, or was it a joke? She mentions Harold Saxon (The Sound of Drums), the moon exploding (Kill the Moon), and then the Minister of War. “Don’t tell me,” says the Doctor in response to that last one, “I’m bound to find out.” Missy? Davros? Or a gag about too-obvious set-ups?

- Why was the bad guy called the Fisher King? It seems more closely related to the Celtic legend than the Arthurian. In that tale, Bran the Blessed (no relation) possesses a cauldron that can bring the dead back to life.

- Also: is the Fisher King at all related to the Vervoids? (Please don’t ask me to explain, I’m not a Year 9 biology textbook.)

- Did anyone pick Peter Serafinowicz as the voice of the Fisher King? I thought he sounded particularly awesome, and now I know why.

- * All right, how does the Doctor’s story about Beethoven tally with the past? Well, the Sixth Doctor was present at Ludwig’s birth in the short story Gone Too Soon. The Tenth Doctor suggested he’d been taught to play the organ by Beethoven in the 2007 episode The Lazarus Experiment, and met him later in the short story The Lonely Computer (the events of which were glimpsed at in The Unicorn and the Wasp). So I think we can safely assume that Beethoven does exist, or did at some point. Some brilliant writer will have to tally this discrepancy further down the line…

- Also: given the apparent revelations about Beethoven’s 5th, were they not tempted to credit the writing of this episode to The Doctor? Or is that way too meta?

–

Throwback Thalday

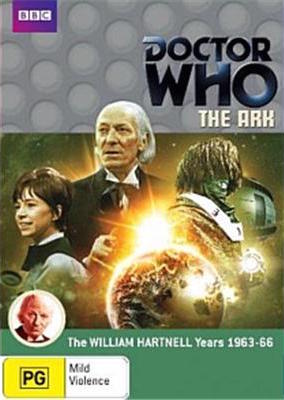

Did you enjoy watching the Doctor jump into the TARDIS mid-way through a story and travel through time but stay in the same location? Then you should check out 1966’s The Ark.

Did you enjoy watching the Doctor jump into the TARDIS mid-way through a story and travel through time but stay in the same location? Then you should check out 1966’s The Ark.

One of the biggest surprises of early Doctor Who came when the Doctor and his companions concluded their adventure and departed, only to find themselves the very next week in the exact same spaceship 700 years later. It was a narrative twist that could only work with serialised storytelling, and a very sophisticated way to look at how civilisations evolve.

–

Doctor Who screens at 7:30pm Sundays on ABC, before reruns at 8:30ppm Mondays and 12:15am Tuesdays.

–

Lee Zachariah is a writer and journalist, who tweets at @leezachariah. Read his Doctor Who recaps here.