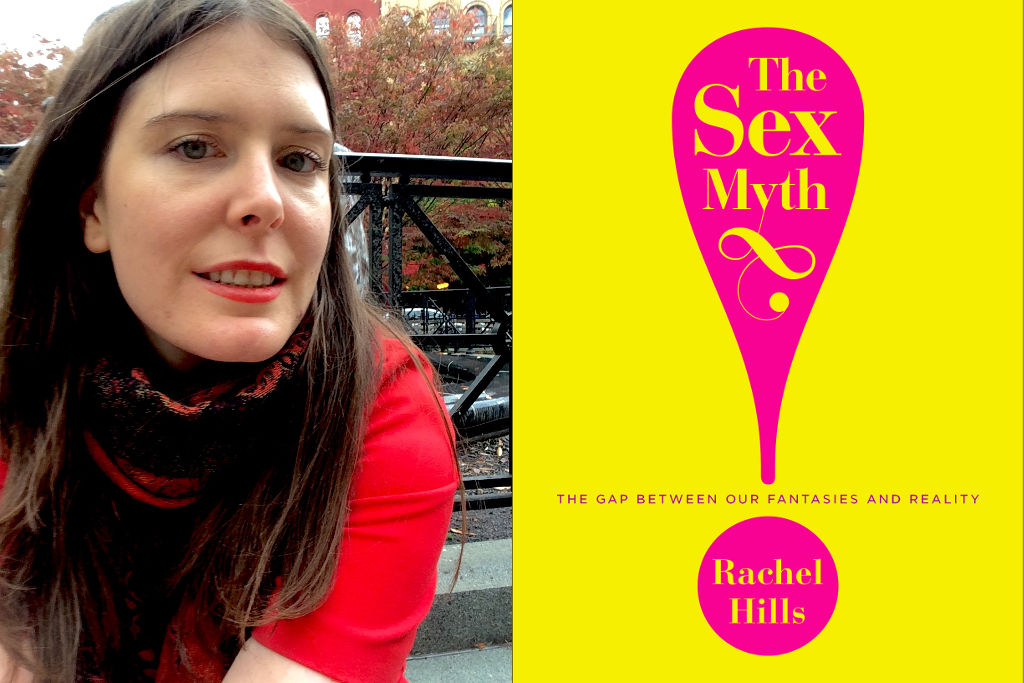

Rachel Hills On Asexuality, ‘The Sex Myth’, And Why Female Masturbation Is Still A Taboo

We also asked the author about sexuality stereotypes in Magic Mike and Trainwreck.

Australian writer Rachel Hills first began thinking about the ideas discussed in her first book in around 2007 or 2008. “There was a lot of stuff in the media about hook-up and raunch culture, and it painted a very exaggerated and hedonistic picture of young people and sex,” she says.

At the time, her sex life didn’t look at all like what shows like Gossip Girl and Sex & the City were telling her it should. To assuage her insecurities, she started writing about sex in magazines and on her blog, and found “lots of other people were feeling the same way. That’s what inspired me to start looking seriously into those ideas.”

She parlayed her interest into a regular column for U.S. Cosmopolitan — and this week, after seven years of research and interviews spanning Australia, the U.K., Canada, and college campuses in the U.S., The Sex Myth: The Gap Between Our Fantasies & Reality was released in Australia.

–

JUNKEE: When you started working with these ideas, what was the gulf like between how sex was portrayed in the media, and your experience of it?

Rachel Hills: I think most of us have the media literacy to be able to look at articles that talk about 17-year-olds falling out of trees while they’re having sex, or “gstringed baboons in oestrus” — which is one of my favourite phrases — and understand that this is not what’s happening on most peoples’ Thursday or Friday or Saturday nights.

What was interesting to me was that those stories were the pointy end of the bigger narrative that was happening around sexuality in our culture. Even if we weren’t hearing these very exaggerated stories, the same narratives were being told in a more subtle, insidious way in magazines, on the web and in TV shows. So there was this overall picture of sex as something that was constantly available and of course you were doing it, and if you weren’t doing it there was something wrong with you.

My personal interest in the subject came from the fact that my sex life didn’t look at all like that at the time, and it was something that I felt a little uncomfortable about; like, maybe there was something wrong with me. When I realised that lots of other people were feeling the same way, that’s what inspired me to start looking seriously into it.

You talk about asexuality in the book. Last year Time Magazine declared a “transgender tipping point”; obviously one is about gender identity and the other sexual orientation or preference, but do you think we’re close to an asexuality tipping point, where people might develop a more inclusive understanding of what asexuality is?

Would we have known five years ago that trans issues would be such a big part of the conversation around gender and sexuality [now]? Not necessarily — because those issues were much more marginal then.

I wonder, what would an asexuality tipping point look like? If it means a discussion of asexuality in the media, then I feel like we’ve already been there. What’s most important in understanding asexuality as a sexual orientation is to come to an acceptance that sex isn’t this constant thing that everybody is always doing and thinking about, and that’s at the centre of everybody’s lives. Like gender, sexuality is a spectrum, so it’s not just that you’re sexual, so you’re constantly humping people, or asexual, and you have no interest at all. We all sit along different points of it. I would like to see an acceptance of the fact that we all have a different interest in sex and access to sex, and we don’t all want to lead the same kind of sex life.

And that we have a different interest in sex, throughout different points in our lives.

Exactly. When I was doing some of my more academic research, I came across a couple of sociologists from the U.S. who were doing most of their publishing in the 1970s, called John Gagnon—great name!—and William Simon. They were the first people to look at sex as a social activity. They look at the fact that sexual desire does change throughout the life cycle. Sex can feel incredibly urgent in youth, the early years of a relationship, or when having an extramarital affair. But there are other times in your life when sex falls into the background, and other things might be a priority.

There was a lot of talk from your subjects about sexual choice; that when a woman isn’t having sex, it’s because she’s perceived as undesirable, whereas for men it’s portrayed as their choice. Can you unpack these double standards a little?

One of the things I talk about in the book is that the feminine ideal that women are aspiring to is no longer this pure, submissive, virgin/wife character that we may have been taught to aspire to in times past. It’s someone who is self-actualised and in control, who has sexual agency, who wants and likes sex. This new feminine ideal, where we’re expected to desire sex, still happens primarily in relation to other people … So her desiring sex means that she says yes to somebody when they want to have sex with her. There’s still a taboo around female masturbation or owning a vibrator, because those things are associated with getting off because you want to, not because you want to please your partner.

In many cases, men brag about how many women they’ve slept with to solidify their heterosexuality. Do you think “bromance” movies like Magic Mike XXL play into or subvert “masculine straightjackets”?

The “masculine straightjacket” is this idea that in order to be a “real man” you have to behave in a certain way. You have to be sporty, good with women, tough; you can’t show emotion, you can’t be a girl and you can’t be gay, because those things are treated as the opposite of what a “real man” is.

In terms of Magic Mike XXL, I think it does challenge some conventional aspects of masculinity. I like that the men in Magic Mike are in some ways incredibly masculine and stereotypically heterosexual, but they’re also allowed to have this softness to them. They’re allowed to be into yoga or dance to the Backstreet Boys, without it threatening their masculinity — maybe because they’re so conventionally masculine in other ways.

But they’re still fist bumping about the women they’re picking up, and their masculinity is still very much derived from their success with women, so I’m not sure that Magic Mike completely challenges [those norms]; it’s still very conventional in a lot of ways.

Have you seen Trainwreck?

Not yet, but I love Amy Schumer so I’m planning on seeing it at some point. I’ve heard about the narrative the film takes [damaged, promiscuous woman is saved by good man], which is weird because it’s not what you would expect from Amy Schumer. She proudly and deliberately talks about the fact that she is sexually active and that she has slept with a lot of people in situations that some people would consider to be unsavoury or promiscuous, and reclaiming that is a big part of her work. So it’s kind of strange that this film would follow that conventional narrative. I wonder if that’s just about the rom-com format, though; it’d be pretty hard to create one that doesn’t end like that. It’d be pretty cool too, though.

It might not have gotten greenlit if it didn’t have that fairytale ending…

That’s a great point. Because films do need a large number of people to see them, compared to books. They really do have to appeal to a broad audience.

I watched a couple of interviews with Amy that have gone viral, and I know that she really rejects the idea that that character is damaged. I think she said in that interview with KIIS FM that she thought of the character as someone who was having fun, and that [the character] didn’t think of herself as damaged. And then things change and she falls in love, hence that conventional happy ending.

Something that I was aware of with The Sex Myth is that I wanted to veer away as much as possible from this narrative: that people’s sex lives weren’t up to scratch but then something happened and oh, they’re having great sex now. It’s a trap I fall into a little bit in the book, but it’s really hard not to because those are the stories people tell about their own lives. We all like to tell our stories about our happy endings; I once was lost but now I’m found; Things used to be bad, now they’re better. That narrative of ‘we’ll be happy in the end when we find a nice man or woman’ is as much entrenched in our culture as the narratives that I talk about in The Sex Myth.

–

The Sex Myth is out now through Penguin Random House.

–

Scarlett Harris is a freelance writer who blogs about femin- and other -isms at The Scarlett Woman. You can follow her on Twitter here.