Queensland Police Are Amazing At Social Media, Except When Something Goes Wrong

If police forces can post funny memes on Facebook, they can post information about allegations of police brutality too.

It’s pretty well-known by now that when it comes to using social media, the Queensland Police Service is in a league of its own. Their Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and YouTube accounts present the polar opposite of what you’d expect from the social media presence of a state police force: they’re funny, engaging, irreverent, tongue-in-cheek.

They post dad jokes. They make fun of Nickelback and Justin Bieber. They take any opportunity to weave a pop culture reference into a post: Star Wars, Lego, Back to the Future. It’s like hanging out with your dorky, slightly drunk uncle at Christmas, only if he also had the power to arrest you.

And it’s worked. Their Facebook page is now the most popular police Facebook page in the world, with more than 700,000 Likes. The QPS Media Unit Twitter account has a similarly impressive 113,000 followers. Their posts, which regularly go viral, get collated into raving articles on a pretty frequent basis: articles from the Courier Mail, the ABC, the BBC, Buzzfeed and others have seen Queensland Police’s social media presence gain global attention.

Other police services across the country and the world have emulated their success. The Victoria Police Force, the South Australia Police Force, the Australian Federal Police, the Harbourside Local Area Command in Sydney and Western Australia’s tiny Yanchep LAC have all jumped on the cool-cop-online bandwagon, turning their routine messages about lost dogs and reminders not to speed over the long weekend into eyeball-friendly fodder that people respond to.

There are obvious and valid reasons why a police force would try to attract this kind of attention. The reach that social media provides enables police to spread public safety information in times of disaster and unrest, help locate missing persons and suspects at large, and even gather info on unsolved crimes. In a 2014 review of their social media strategy, Queensland Police highlighted how Facebook proved invaluable for disseminating vital instructions and reassuring the public during the 2010/11 floods.

But it also serves another purpose, which was thrown into pretty sharp relief earlier this week when footage emerged of a Queensland Police officer repeatedly pushing an Aboriginal woman in the chest and neck during a house arrest. That video has gone just as viral as anything the Queensland Police Facebook page has ever posted, clocking almost 750,000 views on the original video and getting picked up by news agencies and TV stations around the country.

Given their active and prolific online presence, one would expect Queensland Police to release some kind of statement to the public about the incident on the channels through which they prefer to communicate. Four days after that video first surfaced, though, there’s no acknowledgement of the incident — or the subsequent media coverage — on any of their social media platforms. No denials, no clarifications, no reassurances, no link to a media statement. It’s as if the last few days never happened.

To be clear, Queensland Police haven’t been totally silent on the matter; a statement about the incident issued by a spokesperson is quoted in many articles. But issuing a statement to a journalist when pressed for one and proactively informing the public on a matter of public interest are two very different things. Given the level of interest in the story, restricting their response to media outlets when they have a large and convenient platform of their own at their disposal gives the impression that Queensland Police are only interested in courting social media when it suits them, and that incidents that could reflect badly on the Service or its officers.

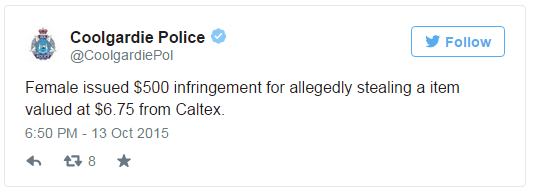

It’s not the first time social media and police haven’t mixed well. In 2014 New York’s infamous #myNYPD campaign, meant to showcase people taking selfies with their local law enforcement, backfired spectacularly after people began tweeting photos and stories of brutal arrests, racial profiling and mistreatment at the hands of police. In October, a tweet from Coolgardie Police detailing the arrest of a young Aboriginal woman for stealing a $6.75 box of tampons was met with a storm of criticism online. That original tweet was pulled down, but not before it inspired a crowdfunding campaign to pay the $500 fine police issued the young woman — and not before plenty of people took screenshots.

These incidents and others highlight the importance of recognising the social media tactics of police forces for what they are: a carefully planned exercise in image management. Social media has given police some powerful tools to reach the public and do their jobs, but a police Facebook page or Twitter account that doubles as a meme factory for people bored at work isn’t a benign or neutral enterprise. Every post that draws your attention to the cute puppies being trained as sniffer dogs serves as a small distraction from news the police deem less convenient, like the multiple instances of alleged police brutality that took place on the Gold Coast in September last year.

In fairness, there are examples of Queensland Police alerting the public to potentially embarrassing information through social media. About a week ago, another Queensland police officer was charged with common assault and deprivation of liberty after an eight-month internal investigation into allegations the senior constable had used excessive force during a traffic stop resulted in his suspension from the Service. The officer’s summons to appear in court was announced on Queensland Police’s social media with a brief summary, along with a link to a more extensive explanation on the QPS News website.

But expecting police forces to be open and honest when they make mistakes is asking the bare minimum of a taxpayer-funded institution invested with immense power. Police can detain and arrest others, use physical and even deadly force, and occupy a vital space in our society; openness and transparency when something goes wrong are the price we expect them to pay in return.

In their own review of their social media strategy, Queensland Police expressed a desire to “engage in a two-way conversation between the QPS and the public”. Social media presents them with a unique opportunity to have that conversation, but not if they refuse to start it in the first place. If Queensland Police can take the time to craft a Facebook post about hoverboards, they can spring to tell the public about a video showing one of their officers pushing a woman in her house.

–