Origin Stories: A Brief History Of Duration Art

Jay Z, The National and Lady Gaga have all jumped on the bandwagon lately, but what exactly is it and where does it come from?

For more original people, places and ideas head to

Everything has its beginning — an inception point or nucleus. We’ve teamed up with ORGNL.TV, a new editorial channel by Stolichnaya Premium Vodka, to bring you a fortnightly series in which we peel back the curtain and pinpoint the moment of origin of something happening now.

–

If you’re a twittering, opinionating citizen of the internet, you will most likely have observed a recent phenomenon, whereby people do things for an unusually long period of time. Unlike trans-continental flight or Test cricket, though, these people aren’t just doing things that happen to take a while: the ‘taking a while’ bit is the whole point of the exercise.

This is durational art. It is art of any discipline — most commonly music, film and performance — that utilises time itself as a core component of the work.

In May, rock band The National collaborated with Icelandic artist Ragnar Kjartansson on an installation at New York’s MoMA called ‘A Whole Lot of Sorrow’, which involved them performing their song ‘Sorrow’ for six hours. In July, Jay ‘no hyphen’ Z performed his song ‘Picasso Baby’ for six hours at New York’s Pace Gallery, alongside performance artist Marina Abramović.

Count the awkward famous people.

Abramovic is perhaps the most well-known crossover from art circles. Her explorations of pain, endurance and mysticism date back to the seventies, and 1974’s alarming ‘Rhythm 0‘ gives you an idea of how far she was willing to go with this stuff. Recently though, she has gained wider renown (and even lost some respect) by leaning on her celebrity connections to spruik for her Abramovich Institute, which offers donors the opportunity to “develop skills for observing long durational performances through a series of exercises and environments designed to increase awareness of their physical and mental experience in the moment” (it also offers us an excuse to watch Lady Gaga nakedly embrace the “crystal of her nakedness”, which is sort of a metaphor but sort of not).

With its move into pop circles, durational art has suddenly become a thing. But where did it come from? And what does it do?

–

Erik Satie and John Cage

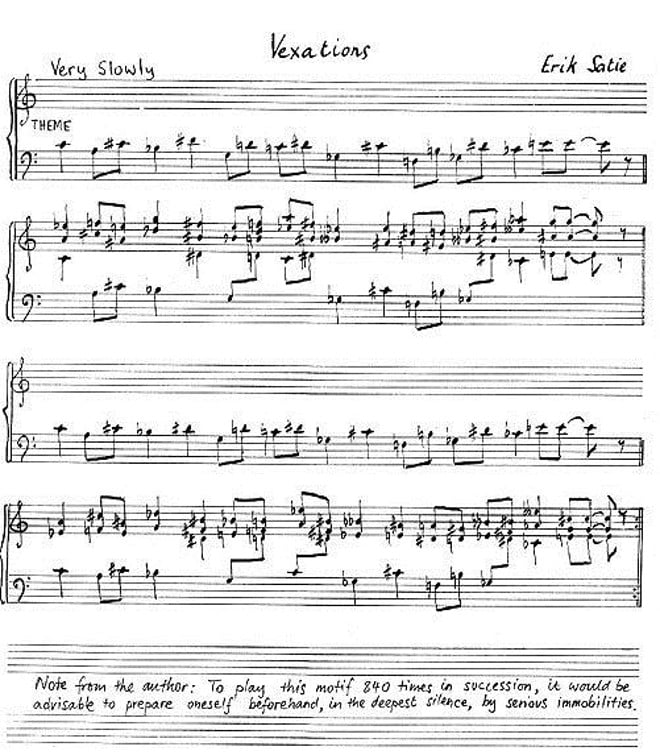

I nominate 1893 as Year Zero for durational art. Written in that year by French composer Erik Satie, his musical work ‘Vexations’ is famously named after the irritating and unnecessary complexity of its notation (although an alternate theory suggests that it is named for its Satanic combination of tritones and its 13-measure duration).

‘Vexations’ is best known, though, for a little composer’s note, which seemingly suggests that the piece is to be played 840 times in succession. The note was cryptic, and possibly a joke, but that didn’t stop the avant-garde composer John Cage organising a recital in 1963. The performance required a relay team of pianists, and it lasted 18 hours.

An English transcription of Satie’s manuscript of ‘Vexations’.

Cage, best known as the ‘composer’ of ‘4’33’, noted that the counter-intuitive notation and disconcerting harmonic patterns of the piece made for an initially unpleasant experience for performer and listener alike, but that the music slowly induced a euphoric state in the audience, which eventually gave way to exhaustion.

–

Andy Warhol

Around the same time as Cage’s recital, Andy Warhol was making films such as Sleep and Empire. Five and eight hours long respectively, these films were static and plotless, perhaps better likened to (slightly) moving paintings than films. By any conventional measure, they were terrible. For Warhol, you sense that this was the point — the experience of the work was secondary to one’s conception of the work.

A thrilling ten-minute excerpt from Warhol’s Empire.

He was applying the logic of Duchamp’s readymades to the fourth dimension: time. As Beckett sought the literature that remained when you ran out of words and Cage sought the notes you heard when your ears had been charred to dust, Warhol effectively smashed the old (and, admittedly, already fatally wounded) notion of art representing a moment of communion between the work and the viewer. What do you see when you watch an unwatchable movie? Nothing, you’ve already left the gallery.

Of course, you didn’t have to watch the films to reach a conclusion about them. As art critic Boris Groys puts it: “One is already satisfied that a certain image can be seen…”, and so the seeing becomes irrelevant. It was art that was more fun to talk about than to engage with.

–

Tehching Hsieh

Where Warhol aspired to elevate himself and his life to the status of art, attaining a glossy surface perfection, it could be argued that Tehching Hsieh was attempting to achieve the opposite: to drag art down to the level of the everyday. His means of doing so were pretty much incredible. In 1978, the New York-based performance artist commenced his series of ‘One Year Performances’ by confining himself to a cell for 365 days: no radio, television, reading or writing.

Hsieh’s second One Year Performance, in which he punched a clock and took a photo of himself every hour.

After his fifth ‘One Year Performance’ — a whole year spent outdoors, a whole year tied to another artist, stuff like that, no biggie — Hsieh raised the stakes with ‘Tehching Hsieh 1986–1999’. He issued a statement, pledging to make art without displaying it publicly for the duration of the thirteen-year ‘performance’. At the conclusion of the allotted time, Hsieh announced that he had kept himself alive, and that he had stopped making art. That was the performance.

–

Duration art today

Back in the present, we are seeing pop culture appropriating the practice and the methods of the aforementioned artists in order to express… what, exactly? What’s the point of it all?

To my mind, durational art, whether occurring at the level of pop culture or high culture, offers up two things that resonate with a contemporary audience. Firstly, it’s a bloodsport: When reading about or observing such a performance, our first thought is for the performer. Oh, they’ll suffer. Can they do it? Will they make it? Roland Barthes proclaimed the death of the author back in the sixties, and yet here we have a sort of artist/genius/martyr whose suffering (or at least discomfort) overshadows the work. Or rather, the struggle is the work.

This is a role more often played by athletes in contemporary society: the avatar, exploring the outer limits of human possibility, planting a flag on our behalf. It feels good to see someone put themselves through the purging fire, and for that person not to be you. If there’s a toe-tapping tune to go with it, all the better. As with sport, the fact that the performer is doing so for arbitrary reasons seems not to detract from the wonderment; it’s beyond reason. Nick Keys’ nomination of Wendy Davis’ recent pro-choice filibuster shows that the phenomenon isn’t limited to art, or at least requires us to radically expand our definition of art.

Secondly, durational art provides a valuable opportunity to contemplate boredom. Not flee from it, as is the custom, but to stare it right in its metaphorical face and to feel whatever one may feel in that moment — unfamiliar feelings and unfamiliar states, borne of the quietude of a focused mind. Such stillness is rare and incredibly valuable, and durational art is one way of trying to attain it. As Abramovic herself has stated: “I have found that long durational art is really the key to changing consciousness… not just the performer, but the one looking at it.”

In such a situation, ‘Picasso Baby’ moves from the idle boasts of a very rich man with a basic working knowledge of contemporary art to… well, anything at all, really. Those syllables blur and unmake themselves. The performer goes beyond the performance, beyond themselves. He enters a trance, you enter a trance. Like a magic eye, it becomes so familiar that it is suddenly rendered strange. This is its genius.

Six hours of ‘Sorrow’ seems like a drag, though.

–

Edward Sharp-Paul is a freelance writer and drink-pourer from Melbourne. He mostly likes music and the sportz, and his words can be found at FasterLouder, Mess+Noise, Beat and The Brag. He also runs his mouth off under the cunning alias @e_sharppaul.